New Raman Spectroscopy Probe Could Improve Outcomes In Brain Cancer Surgery

Scientists have developed a new intraoperative probing technique that could increase survival odds for patients with brain cancer. The McGill University researchers claim that a Raman spectroscopy probe can be used during surgery to accurately identify almost all invasive brain cancer cells that other methods could potentially miss.

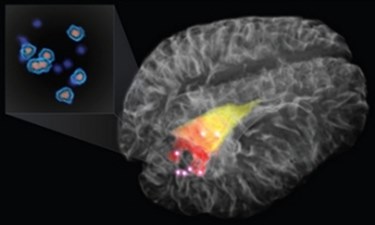

The Raman spectroscopy probe is hand-held and uses laser technology to measure scattered light and provide more specific information about the molecular makeup of targeted brain tissue. Researchers believe this greater specificity will allow brain surgeons to remove more cancerous cells than they were previously detectable, according to a McGill University press release.

The collaborative team that developed the probe includes scientists from the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital – The Neuro, McGill University, the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC), and Polytechnique Montréal. The team published their findings in Science Translational Medicine (STM).

The STM study said, “Using this probe intraoperatively, we were able to accurately differentiate normal brain from dense cancer and normal brain invaded by cancer cells, with a sensitivity of 93 percent and a specificity of 91 percent.”

Traditional imaging technology such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can easily identify solid tumors, but other cancerous cells that have invaded healthy tissue on the periphery of the tumor often remain undetected.

“Often it is impossible to visually distinguish between cancer from normal brain, so invasive brain cancer cells frequently remain after surgery, leading to cancer recurrence and a worse prognosis,” Kevin Petrecca, chief of neurosurgery at The Neuro and co-senior author of the study, said in the press release.

Petrecca told the Montreal Gazette that the results from the probe appear on a laptop within seconds of coming into contact with brain tissue, allowing surgeons to perform more thorough resections.

Researchers tested the probe on patients diagnosed with grade 2, 3, and 4 invasive gliomas and found that the probe was equally effective in detecting cancer cells from all three grades.

“There is strong evidence that the extent of tumor removal affects prognosis for all grades of invasive gliomas,” said Petrecca in the McGill press release.

The research team announced plans to launch a clinical trial at the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital to confirm whether or not the new system improved outcomes for patients with glioblastoma.

Mark Bernstein, a neurosurgeon at Toronto Western Hospital (unconnected to the research), told the Montreal Gazette that he applauded the development but expressed his doubts about its feasibility.

Bernstein explained that removing every cancerous cell could damage brain function. Furthermore, genetic markers that put the patient at risk of cancer in the first place could cause a recurrence regardless of how many cancerous cells are removed. It is Bernstein’s belief that the future of glioma removal will be pharmaceutical rather than surgical.

According to the American Brain Tumor Association, nearly 70,000 new cases of primary brain tumors are diagnosed each year, and brain tumors are the leading cause of death in children under the age of 20. Gliomas represent 30 percent of all brain tumors and 80 percent are malignant.