Change Impact Assessments: How To Fix Something Without Breaking Everything Else

By Alan M. Golden, Design Quality Consultants

In life, as well as in the medical device industry, change happens. One of the only guarantees in new product development — or post-launch support of that product — is that something will change. However, unlike life in general, the medical device industry must abide by specific rules regarding how you handle change; more to the point, regulatory and product-governing bodies have some very specific ideas about how you manage changes to your product.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) 21 CFR Part 820 (Quality System Regulation), Sec. 820.30, part (i) states: “Design changes. Each manufacturer shall establish and maintain procedures for the identification, documentation, validation or where appropriate verification, review, and approval of design changes before their implementation.”

Meanwhile, ISO 13458:2016, Medical devices — Quality management systems — Requirements for regulatory purposes, section 7.3.9 (Control of design and development changes) states:

The organization shall document procedures to control design and development changes. The organization shall determine the significance of the change to function, performance, usability, safety and applicable regulatory requirements for the medical device and its intended use. Design and development changes shall be identified. Before implementation, the changes shall be:

a) reviewed;

b) verified;

c) validated, as appropriate;

d) approved.

The review of design and development changes shall include evaluation of the effect of the changes on constituent parts and product in process or already delivered, inputs or outputs of risk management and product realization processes. Records of changes, their review and any necessary actions shall be maintained.

That all said, neither guidance document provides much actual guidance. They leave it up to the firm to determine the appropriate level of work necessary to manage changes, as well as how to define what is “appropriate.”

This is where the concept of a change impact assessment comes in. It is in the impact assessment that the team (more on the “team” concept later) decides the best path to compliance with all applicable guidances. It is critical that the firm has comprehensive, well-written, and descriptive procedures not only for documentation, but for assessing the impact of any and all changes, no matter how minor. Further, even if the firm considers its change “minor,” the assessment that led to that determination must be documented.

Three Elements of a Change Description

On the surface, the three basic parts of a change description seem to be simple concepts, but they also seem to cause a lot of consternation and confusion. These three are the change itself, the reason, and the justification. All changes share these components, no matter how simple or complex the change. So, what does each entail?

The change is a succinct, accurate, and specific description of the change (or each change) you need to make. This description should be sufficient to explain what is changing to what — no more, no less.

The reason is a succinct, accurate, and specific description of why you are making the change (or changes). No one makes changes for fun; there has to be a reason., and this is the place to detail that reason. The most common mistake in the “reason” description is inclusion of justification (or a description of the reason that reads like a justification).

The justification is a statement of why it is acceptable to make the change, including some statement of the change’s impact on the product, manufacturing process, or other impacted areas. If there is no impact to other aspects of the product, process, business, or anything else, this too must be stated, with objective evidence either detailed in the statement or referenced.

If impacts are identified, the justification must include a description of how that impact was or will be mitigated, or evidence that a risk analysis was completed and the risk was deemed acceptable. The most common “justification” error I have seen is when firms simply restate the “reason.”

So, where does the justification come from? It comes from the impact assessment. There is no way to justify a change unless you do an impact assessment, which is not quite a one-size-fits-all scenario. To avoid conducting a full impact assessment on changes that are truly simple corrections or adjustments, the firm needs to clearly define what would be considered “low or no-impact” changes. This guidance and list of low-impact changes should be a part of standard operation procedures (SOPs) and not subject to interpretation or exception.

Some changes that may be considered low-impact, and thus not subject to full impact assessments, include:

- Document name changes or format changes that don’t affect content; grammar or spelling corrections that don’t impact meaning

- Changes to internal product labeling that is not customer-facing

- Removal of redundant information in a document

- Deleting alternate parts or vendors, as long as at least one original part or vendor remains. Note that adding alternate parts or vendors would not be considered a low-impact change, even in cases of a “like-for-like” part (you have to prove like-for-like).

This is not a long list, nor should it be — changes permitted without a full impact assessment should be limited and well-defined.

Assembling An Impact Assessment Team

If it is determined that a change requires a full impact assessment, the first step is to assemble a team to complete the assessment, as it is not possible for an individual to complete a thorough impact assessment. Such an assessment requires expertise from a diverse group of people with varied skill sets. For most changes (excluding those specifically defined low-impact changes), the following individuals (or groups) should be considered for the assessment team:

- Someone to drive the change — This is the most important team member, acting as the project manager to keep the change moving forward and coordinating all necessary activities not only to complete the impact assessment, but to ensure all necessary actions stipulated by the impact assessment are completed so the change can be implemented. Normally, this is the person (group) that wants the change, but it does not have to be. Many companies have dedicated change teams with dedicated change managers.

- Technical — This can be R&D, postmarket technical support, or both, depending on the product or process’ stage in the product lifecycle.

- Quality Assurance — This may include design quality, field quality, supplier quality, and/or manufacturing quality, depending on the change.

- Manufacturing and/or process technical personnel

- Regulatory Affairs — Many changes require a regulatory assessment and potential regulatory filing or pre-approval.

- Validation — Many changes impact validations, so representation by the validation team is essential.

- Marketing — If the change is customer-facing or impacts labeling, marketing should be involved.

- Engineering — Changes that involve facility, utility, or equipment impact will benefit from engineering input, in conjunction with validation support, if needed.

- Quality Control — involved if there are changes to testing or test methods

- Risk Management — Assessment of the product’s risk profile always is part of a change impact assessment.

- Environmental Safety — If the changes could impact environmental safety or health, a representative from this team should at least be consulted.

- Production Planning — If the changes will impact production, this team should, at a minimum, be consulted.

This may seems like a lot of people to try to pull into a room to create an impact assessment, but a change initiator attempting the assessment solo is likely to miss many important impacts of the change, or to inaccurately determine impact. Also, a single person rarely has the expertise necessary to make the impact decisions across the board, let alone come up with justifications for “no impact” or the steps needed to show impact mitigation.

Still, note that the above list is not exhaustive; nor does every discipline need to be part of every change.

Creating A Change Assessment Roadmap

Even for a skilled, experienced team, it is almost impossible to work through all possible areas where impact must be assessed without a proper template to facilitate the discussion and provide a place to record decisions and justifications. This form can be an embedded form in an electronic document control system or created in Microsoft Word. The format is not as important as the document’s goal: to guide the change team through the impact assessment process and provide a place to record impact decisions and actions.

There is no single perfect design for this form; it will vary according to the firm’s needs. But, in general, it should have three main sections:

- A place for standard information, such as the initiator’s name, product name and/or number, potentially part or system number, document, or some way to identify what is being changed. I also like to include the names of change team members.

- A place to describe the change and the reason for the change (see above). There is no justification at this stage, as the change justification comes directly from the impact assessment! It is hard to know the justification if you don’t first know the impact of the change.

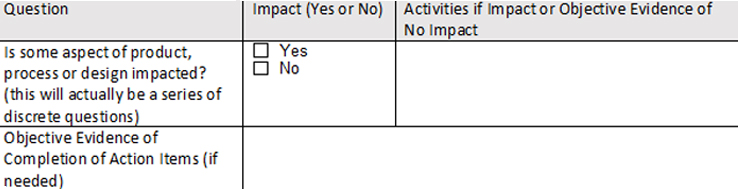

- Third is the impact assessment itself. One format that works well entails framing the assessment as a series of questions that can be answered by the team as it works through the areas of potential impact. Key to this concept is that no question is left unanswered. An example of this approach is depicted in the table below (Fig. 1):

Fig. 1 — An Impact Assessment Template Example

Regarding the table’s layout, each impact question should have its own row. Second, the impact question in the second column comprises a simple check box. The third column, where the impact decisions are justified, is key. If there is no impact for a given question, it is not sufficient to say “there is no impact” in the third column (that simply repeats what you said in the checkbox); you need to justify why there is no impact. You can point to other controlled documentation, use logic, literature, or other source material, but even a decision of “no impact” has to be justified.

If there is impact, the third column is where you would outline any activities or plan needed to verify/validate the change. These might include additional or repeated studies, additional or extended process or test method validation, new supplier qualification, or any number of activities the team decides are required to ensure the change is effective and does not adversely impact the product in question, another product, or any other aspect of production. If the list is long or detailed, it is acceptable to reference an attachment(s) to the form.

Concepts of design control provide the best place to start developing your list of guiding questions. The process flow through design control (Fig. 2) provides an excellent framework on which to build the impact assessment:

Fig. 2 — Process Flow Through Design Control

As an example, the form’s initial question could be phrased “Is there a change to User Needs, including Intended Use and/or Intended User, or does the change have the potential to impact the ability to meet current User Needs, and/or Intended Use?” The granularity of each question can be adjusted depending on the needs of the organization, complexity and class of the product, and the sophistication/experience of the teams.

After impact questions following the design control flow are developed, additional questions can be added to the form to capture additional areas in need of consideration, which may include, but are not limited to:

- Facilities or utilities

- User interface (if one exists)

- Formulation changes (may be part of design specifications section)

- Risk management files or product risk profile (very important)

- Impact to product labeling

- Additions or updates to process, test method, facility, computer, or other validations

- Potential impact to existing or distributed material

- Impact to other products not directly related to the change

- Product stability, storage, or shipping

- Impact to suppliers

- Regulatory impact

Of course, the assessment and action plan should be approved by the appropriate team members, a change review board, or management, if required by company procedures. Required approvals should be outlined in an SOP.

Understanding Risk Management and Regulatory Impact is Critical

For every change, it is vital to perform a complete risk assessment of the change and to document the process. This is especially critical if the change is adding or removing functionality and/or is being driven by CAPA or customer complaints. Updates to the product’s risk management file may be required, as well as updates to risk documentation relating to production, as a result of addition or removal of control measures or addition, modification or removal of testing.

Regarding the product’s regulatory profile, many medical devices — especially class II and class III devices — may need updates or additions to annual reports, or potentially supplements to the product’s regulatory filings. Many changes require pre-approval from regulatory agencies prior to implementation. Failure to properly assess the impact of the change to the regulatory profile could result in enforcement action.

Further, any actions coming out of the impact assessment that need to be completed prior to change implementation must be documented as complete. These could include activities to verify and/or validate the change, update risk management files, or complete regulatory filings. That is the intent of including the last row in Fig. 1.

At some point before the change in put in place, this space provides a way to reference everything that has been completed. Since all steps have been properly documented, all that is required here are references to where those documents can be found. After objective evidence of completion of all required tasks is recorded, the final impact assessment can be approved and the change(s) implemented.

If results of the actions outlined in the impact assessment indicate that the change has an adverse impact on the product, process, production, or another product, the change should not be implemented. The team will need to reevaluate the change’s criticality and, if the change is deemed critical, this revaluation could drive additional activities — including an update to the change profile or a product redesign. The purpose of the impact assessment and action plan is to determine whether the change will be good for the product. Not all changes are, and that is also valuable information.

Conclusions

Audits reveal one of the biggest advantages to using a system like the one I’ve described. An auditor or investigators routinely ask to see product changes, either during development or postmarket. Documenting all changes in this way allows the auditor or investigator to quickly see that all areas of potential impact were considered and were acted on, if required. It also shows that the company has a system and procedures in place to adequately assess the impact of changes, and shows that all changes are addressed in the same way. Since all relevant documents are referenced, it is easy for the audit team to act on any follow-up questions or requests from the auditor.

Whatever system you put in place will go through several rounds of modification as it matures. User groups will come up with new or modified questions, better and more efficient forms, and additional guidance, as needed. Of course, company SOPs should reflect the requirement to perform complete impact assessments for all changes, except the limited set pre-defined as low- or no-impact.

A learning and acceptance curve is normal and is to be expected when introducing more formal and required impact assessments. Setting up user groups, internal subject matter experts, and question-and-answer sessions will go a long way toward acceptance and compliance. Once in place, the advantages of a comprehensive change impact assessment system quickly become evident.

About The Author

Alan M. Golden is the Principal at Design Quality Consultants, where he provides consulting and training services for the medical device industry in Design Control, Change Control, Risk Management, process/test method validation and statistics. He spent more than 30 years in various research and quality roles for Abbott Laboratories. Alan holds a master’s degree in molecular biology from the University of Illinois at Chicago and a B.S. in microbiology from the University of Michigan.