How To Develop A Quality Policy Built On Risk Management

By Marcelo Trevino, independent expert

By Marcelo Trevino and Thomas Bento, Nihon Kohden America

In today’s challenging regulatory compliance environment, it’s not uncommon for companies to establish a quality policy that satisfies regulatory authorities, but doesn't truly resonate with the organization.

that satisfies regulatory authorities, but doesn't truly resonate with the organization.

A quality policy is cross-functionally developed by management and quality experts to express the organization’s quality objectives. The policy’s purpose is to express the acceptable level of quality for the organization, and to outline the standards applicable to specific departments. When defining a quality policy, include the following characteristics:

- Clarity — Define objectives that can be clearly understood and are easy to remember.

- Longevity — Offer a long-term perspective that is unlikely to be impacted by market or technology changes.

- Challenge — Drive continuous improvement and stretch goals.

- Simplicity — The policy should be general enough to encompass all of the organization's interests and its strategic direction.

- Inspiration — Motivate employees to achieve a desirable outcome.

Section 5.3 of ISO 13485:2016 calls for top management engagement with product quality and maturity, ensuring that the policy:

- is applicable to the purpose of the organization;

- includes a commitment to comply with quality management system (QMS) requirements and to maintain the system’s effectiveness;

- provides a framework for establishing and reviewing quality objectives;

- is communicated and understood within the organization;

- is reviewed for continuing suitability.

To measure whether a quality policy is adding value to the organization and is effective in its implementation, we can we quantify the policy’s objectives using these steps:

- Policy statement — The policy should include all of the elements described above.

- Objectives — Objectives are stated and achievable. Extract them from the policy and begin planning around those objectives.

- Planning/Action — Document the planning of each objective. This will include enumerating the tasks for each objective. Assign a description, date, and resource to accomplish each task.

- Metrics — Metrics can be structured through the tasks that are associated with each of the objectives.

- Monitoring — Monitor objectives closely, ensuring that each is being met consistently.

Furthermore, don’t be intimidated when it comes to modifying the quality policy. As the business develops and matures, objectives and direction will change. Ideally, if objectives are quantified and reflect the company’s commitment to quality, it will be necessary to change the policy at some point. For example, if greater efficiency is one of your objectives, and you have achieved your efficiency goals, you may find more value in restructuring your policy around risk management objectives.

Example: A Risk-Based Quality Approach

Policy — “...Our company is committed to meet customer expectations through a risk-based approach…”

Objective — Implement and maintain a risk-based approach. (WHAT)

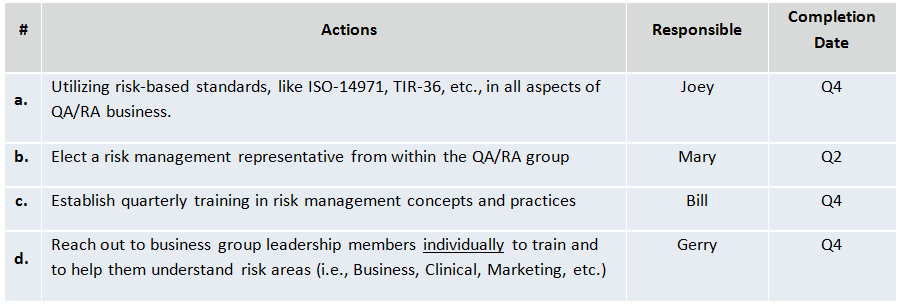

Planning/Action — The following table can be used to outline the actions, responsible parties, and completion time frame for each task. (HOW and WHEN)

By incorporating risk management in the quality policy, the organization basically is adopting a preventive action approach to most activities performed under its quality system, a practice in alignment with the latest ISO 13485:2016 expectations. Risk management can be used after policy implementation for continuous improvement, as well. In doing so, actual (hard) data should be available to help determine customer (external and internal) requirements and to quantify failures for failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA). Used before quality policy implementation, risk management provides the initial risk-analysis needed to make good decisions, establish elements of an organization, or meet the requirements of sound project planning.

Metrics — For task (a), the identification of each relevant standard can be enumerated, and then used to represent the completion of this task. Action (b) can be easily quantified by the election and training of a risk management representative. This can go on for each action on the table. Additionally, one can quantify the whole objective based on completion of each action.

Monitoring — Checks and balances on each objective ensure the state is maintained.

Avoid the pitfalls that come with overwriting the policy, common traps like making it too wordy, including information that adds no value, or making it nebulous enough to where people find it inaccessible or have trouble understanding it. Think about your planned policy objectives, and then ask yourself and other cross-functional groups how those objectives will translate into quantifiable measurement key indicators / dashboard information.

Managers can use the following questions when conducting review meetings to determine if measurement indicators are adequate:

- Are the key objectives and indicators on the company dashboard the ‘‘best’’ to attain the organization’s quality policy? Assess if any areas have adequate representation and ensure there is a consistent balance: quality, process, supplier performance, etc.

- What products or services are most critical to your organization achieving its quality policy? List the top products and services and assess if targets are being met in a timely fashion for all key quality objectives

- Are measures defined based on current or future risks? Assess measures are adequate, and senior leadership is aware of these risks

A dashboard is a valuable tool that focuses employee efforts on their organization’s quality policy. This is accomplished by developing a cascading and interlocking system of key quality objectives and indicators throughout all levels of the organization. Each employee can identify his or her key quality objectives by studying his or her superior’s key quality indicators and, consequently, his or her process performance projects or tasks. Dashboards present a simple and easy-to-understand system for management that promotes enhanced process performance.

Use FMEA To Manage Risk

Failure mode and effects analysis is as useful in setting strategic business direction as it is effective in product development (its conventional purpose). Using FMEA, organizations can avoid expensive modifications to design elements by identifying and preventing potential failures, or by assessing which risks must be taken and determining ways to mitigate their consequences.

FMEA should examine performance under extreme conditions, including potential misuse of the system — for example: using an unqualified workforce, stretching human resources beyond their intent, pushing equipment run-time or life-time, or repackaging old designs as new ones without the proper control mechanisms. While the FMEA will include intended uses and expected misuses of system elements, component failure is of the most interest, as that is the first-line breakdown of higher-level failures, such as products or enterprise systems. Organizations should also take into account the effect of several component failures as a system in their risk management practices.

The failure of a component has an associated mode (symptom), as well as a cause, and a distinction must be made between FMEA and simple root-cause analysis. Root-cause analysis typically is used to diagnose failures that have occurred, and to associate specific reasons to them, typically through the Corrective and Preventive Action process and it looks at the failures retrospectively. FMEA examines potential causes of failure for their effects on the system, and attempts to prevent them. It is a forward-looking approach, using the failure mode (symptom of a failure) to help assess the risks associated with potential failures, as well as determine the cause and the ultimate effect on the system. The failure mode in FMEA is the observed condition of the failed component, not the cause.

Risk analysis is an important consideration of the FMEA. Information provided on the likelihood of failure (the expected frequency of a functional failure occurring) and the failure effects (consequences of a failure when it does occur) is used to characterize risks. The frequency times the consequence is a weighting mechanism used to compare various component failures. Frequency and consequences are estimated independently, and then multiplied together.

Learn how to assess your existing quality system and what changes you will need to implement to comply with the revised ISO 13485 standard. Register for Marcelo Trevino’s upcoming online seminar:

Analyzing and Understanding ISO 13485:2016 Changes

August 30, 2016 | 1:00-2:30PM EDT

Failure frequency is extracted from actual data, or other risk-assessment tools may be used to provide an estimate. Higher likelihoods are weighted higher. Failure effects (consequences) should be based on the failure of the component’s function (what happens to the needed function if the component fails) without regard to its likelihood. Components whose function(s) are key to the entire subsystem or system will have the highest weights. Components whose functional failure will simply impede the system or its efficiency will have a lower weight. Applying this to critical business strategies, initiatives and key processes can provide significant input to define a risk based quality policy and objectives.

While all failures are of concern, and all components serve a purpose (or they shouldn’t be in the system), they do not have equal criticality. Considerations of criticality include the ability to prevent failures and to mitigate their consequences should they occur. Ability to take action is an important aspect in assigning risk, as well. Backup systems, contingency plans, and alternative resources lessen the risk because they affect the consequences of failure (though not the likelihood of failure).

Effectively Deploying Quality Policy Objectives Throughout The Organization

Key quality objectives are deployed through assigning responsibility for action to people (or groups of people) in each area/department. A management dashboard system requires areas or departments to establish cascading key indicators that are aligned with the overall organization’s quality policy and quality key indicators. Each area and department is held responsible for developing process improvement projects or tasks to enhance the results of their relevant key indicators on a regular basis.

This process continues until all parties reach a consensual agreement on projects. Assigning project responsibility to a manager creates an opportunity to improve or innovate ‘‘best practice’’ methods and the allocation of necessary resources, as well as an obligation to predict the contribution of projects to strategic objectives and the risk based quality policy.

Project or task deployment is complete when a project team has been assigned responsibility to improve or innovate a method. Departmental key objectives can include departmental improvement plans (tactics) needed to promote those objectives. Project(s) necessary for each departmental key quality objective should be clearly defined, and each manager assigned a project should formally indicate his or her acceptance of the project. Channels of communication and types of departmental coordination needed to carry out the projects should be defined. The manager of each department named as a necessary supporter of a project also should formally indicate acceptance of the responsibility. Finally, financial and human resources needed to carry out the projects shall be defined.

Organizational leaders need to consider whether information channels exist between all relevant people and groups to promote the improvement plan. Think of long-term projects that could use safety assurance (complaints from the field / post market surveillance data) as a way to avoid challenges from regulators and to improve the product for new generations.

Assuming that all objectives are important and that these objectives are subject to uncertainty, there is risk in all organizations, and the first step toward effective risk management is recognition of that risk. Once each risk is clarified and communicated to affected departments and individuals, steps must be taken to mitigate the risk, or to reduce it to acceptable levels. This process requires context that applies to the specifics of the organization, a means of assessing and analyzing risk, and a process for treating risk. Communication, monitoring, and review are vital, as is an understanding of applicable standards, training/education, and documentation.

The concept of risk is fast becoming part of the general day to day application of quality. However we define quality and related disciplines, there is no question that risks are counter-productive to quality and that risk management can be considered a quality-preserving activity. It is important for quality professionals and practitioners to better understand the new risk paradigm in the context of their organizations and to leverage quality policies to facilitate the introduction of this concept. ISO 9001:2015 provides an excellent mechanism to identify opportunities that will enhance organizational processes through risk and we should expect other standards and regulations to follow in the near future.

About The Authors

Marcelo Trevino is Senior Director of Quality and Regulatory Affairs for Nihon Kohden America.

Thomas Bento is Sr. VP of Quality, Regulatory, and Clinical assurance for Nihon Kohden America.