Nasal Test For Human Prion Disease May Accelerate Search For A Cure

By Chuck Seegert, Ph.D.

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is an incurable disorder that leads to the degeneration of a patient’s central nervous system, eventually leading to death. In the past, the only way to diagnose CJD was to take a post-mortem brain sample or perform a biopsy. Now, however, a relatively non-invasive test has been developed that may assist researchers in finding a treatment for the disease.

CJD is a disease caused by prions, which are small protein molecules that exist normally in humans and animals. Generally, these proteins are harmless, but for reasons unknown they are capable of forming clusters that lead to the destruction of brain tissues. Prion disease strikes humans and a number of animals including sheep, deer, and elk. In cattle, the disease is known as bovine spongiform encephalitis, or mad cow disease.

The human versions of the disease are known as familial, variant, and sporadic CJD, and the sporadic type affects up to one million people globally per year. With the accumulation of the prion clusters, the brain develops holes as it degenerates, leading to sponge-like damage in the tissues. The current method of diagnosing CJD requires a tissue sample to be taken — something that is not easily done and is generally left until later in the disease process when symptoms become more prominent.

While there is no cure for CJD at present, the development of this relatively quick and much less invasive test would enable diagnosis at earlier stages of the disease. Finding it sooner would allow characterization of how CJD progresses and perhaps provide insight that would allow researchers to arrest or cure the disease.

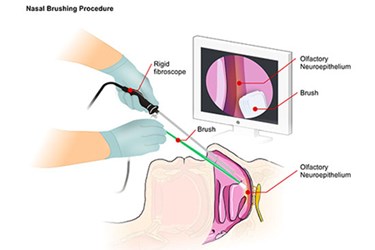

In a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine by the NIH and a number of Italian research institutions, a new method using scrapings from the olfactory epithelium was described. The olfactory bulbs, the sensory organs that allow people to smell, are considered part of the central nervous system, since they connect directly to the brain. These olfactory bulbs reside in the nasal passages, and scraping this tissue is done directly through the nose, which eliminates the need to access the brain directly.

In the study, results from the nasal specimen were compared to those from the traditional diagnostic methods that used cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Both diagnostic tests were run on each patient involved in the study, allowing for a direct comparison of the accuracy for each assay.

Overall, the new nasal brushing approach was shown to have a 97 percent sensitivity to the presence of CJD and was 100 percent specific. In contrast, the CSF samples taken from the same group of patients exhibited a sensitivity of 77 percent and a specificity of 100 percent. This indicated that the nasal brush method was more likely to detect the presence of CJD, because the prion seeds in the epithelial scrapings are many orders of magnitude greater than those seen in CSF.

“This exciting advance, the culmination of decades of studies on prion diseases, markedly improves on available diagnostic tests for CJD that are less reliable, more difficult for patients to tolerate, and require more time to obtain results,” said Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), in a recent press release from the NIH. “With additional validation, this test has the potential for use in clinical and agricultural settings.”

While the development of new diagnostic tests is moving forward, efforts to develop treatments for CJD are also being pursued. Laser-based methods of disaggregating the prions that clump together are among the most promising.

Image Credit: NIAID