New Devices Test Efficacy Of Multiple Cancer Drugs Simultaneously

Two new devices may offer oncologists a way to quickly “test drive” a variety of cancer drugs before committing a patient to a course of treatment. By further developing the technology, scientists hope to eliminate the trial-and-error methods currently used and potentially accelerate drug development with safer and faster clinical trials.

Finding the best cancer medication for a given patient can be a months-long ordeal and cause a great deal of suffering. Recent research has attempted to test cancer medications on tumors grown on mouse models, but these methods are expensive and also can take over a month to complete.

Two new studies published in Science Translational Medicine (STM) introduce devices that can test the efficacy of drugs in vivo and deliver results in 24 hours, a development that experts say could be transformative to personalized cancer treatment.

The first device, developed by team from the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), is approximately the size of a grain of rice. Once injected into the tumor, the device releases microdoses of cancer drugs into separate regions of the tumor. After 24-hours, the tumor is removed and analyzed. In the study, the MIT team reported the device could test up to 16 drugs or drug combinations at the same time.

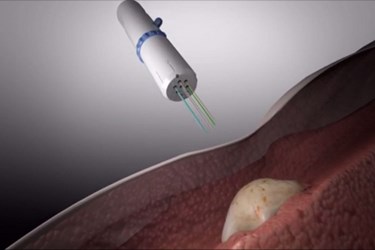

In a separate STM paper authored by a team from Presage Biosciences, a team led by Richard Klinghoffer describes another device that uses six long needles to inject drugs that are dyed different colors. The technology platform, called CIVO, can test up to eight different drugs or drug combinations. Researchers say that the technology is currently suitable for animal models or superficial tumors, but that it could be developed for deeper malignancies.

Both devices were tested on mice, and researchers found in both studies that they could correctly predict which cancer medicine would kill the most cancer cells. The team from Presage Biosciences did some limited testing on humans and found that their methods were well tolerated.

Alongside the two studies, STM published a comment piece by R. Charles Coombes, a professor of medical oncology from the Imperial College London, who evaluated the devices and their impact on clinical oncology.

“If implemented in clinical practice,” said Coombes, “these devices have the potential to reduce indiscriminate drug use, to improve survival, and to reduce unnecessary adverse effects.”

In an interview with NewScientist, Neil Watkins from the Garvan Institute in Sydney, Australia, said that the devices were a simple and elegant solution to difficult problem and they may help expedite clinical trials in humans by providing safer and faster results.

“This can fast-track our ability to rethink standard chemotherapy and deliver it in a more effective and safer way. Even if all this did was help you identify patients that you don’t want to treat with toxic therapy, that would be a major advance,” said Watkins.

Image credit: Presage Biosciences