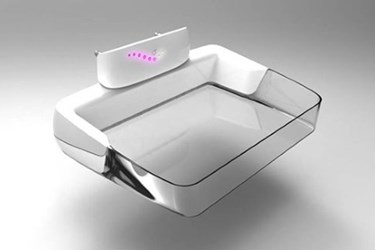

New Medical Device Could Make Mammography More Comfortable

By Chuck Seegert, Ph.D.

A new device may lead to more comfortable mammography for women. By using a standardized pressure to compress the breast, pain can be reduced without an impact to image quality.

Mammograms are a critical tool for the diagnostic examination of the breast, as they are an important screening procedure for breast cancer. Typically, they utilize low-energy X-radiation that provides a radiograph of the breast tissue and the masses that may be present within it. To increase the uniformity of exposure, the breast is compressed or flattened using paddle-like equipment. The goal is to shape the breast tissue into a mass of tissue that is an equal thickness all around.

Compression of breast tissue is often considered one of the least pleasant parts of the exam, as it can be quite painful. Now, however, researchers from the Department of Biomedical Engineering and Physics at the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam may have found an alternative approach to compression that could help, according to a recent press release from the Radiological Society of North America.

The new method could be incredibly important, since discomfort and pain associated with compression has been known to deter women from having mammograms, according to the press release. Currently, some 39 million mammograms are performed each year just in the United States, with more than 156 million compressions associated with these exams.

Currently, compression is accomplished by applying a standardized force to the breast, which can lead to pain and some variability between exams. To alleviate this, Dr. Branderhorst and his team hypothesized that pressure measurement may be more effective. Pressure is a ratio of force over the area which it is being applied, while force alone is the effect one object has on another. To use pressure during the compression process, the contact area of the breast would need to be measured. To be implemented, this would only require a small modification to the existing compression apparatus.

To understand the effects of using compression instead of force, Dr. Branderhorst undertook a study with his team that included 433 asymptomatic patients, according to the press release. For each patient, four exposures were performed and, of those, three were taken with the standard force application of 14 dekanewtons. The fourth exposure, chosen randomly, was performed using 10 kPa of pressure. Overall, the scoring of the images by radiologists showed that the pressure-based compression method did not compromise image quality and, on average, the patients reported it to be less painful.

"Standardizing the applied pressure would reduce both over- and under-compression and lead to a more reproducible imaging procedure with less pain," Dr. Branderhorst said in the press release.

The pursuit of better imaging for breast cancer diagnosis and screening is an active area in the medical device space. In addition to mammograms, some researchers are using MRI to more accurately study breast tissue, thus eliminating some biopsies that may result from false positives seen with mammograms.

Image Credit: RSNA