Cell "Herding" Could Lead To Smart Bandages

By Joel Lindsey

Researchers at UC Berkeley have experimented with using electrical currents to “herd” cells, claiming the technique could improve the body’s wound healing processes.

“The ability to govern the movement of a mass of cells has great utility as a scientific tool in tissue engineering,” Michel Maharbiz, associate professor of electrical engineering and computer sciences at UC Berkeley and lead scientist on the cell herding experiments, said in a statement released by the school. “Instead of manipulating one cell at a time, we could develop a few simple design rules that would provide a global cue to control a collection of cells.”

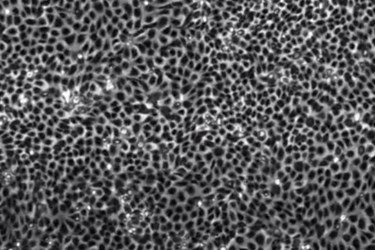

In the experiments, described recently in the journal Nature Materials, Maharbiz and his team applied electrical currents of roughly five volts per centimeter to control and direct the movements of large clusters of epithelial cells, which help hold together important structures such as skin, kidneys, corneas, and other organs.

The team reported successfully guiding the cluster of cells, causing them to flow from left to right, to diverge and converge, and to make more elaborate movements like U-turns. They were also able to herd the cells into complex shapes.

“This is the first data showing that direct current fields can be used to deliberately guide migration of a sheet of epithelial cells,” said Daniel Cohen, a member of Maharbiz’s research team. “There are many natural systems whose properties and behaviors arise from interactions across large numbers of individual parts — sand dunes, flocks of birds, schools of fish, and even the cells in our tissues. Just as a few sheepdogs exert enormous control over the herding behavior of sheep, we might be able to similarly herd biological cells for tissue engineering.”

Researchers hope to apply these discoveries to the natural processes of wound healing. In particular, Maharbiz and Cohen have reported an interest in applying their work to the development of “smart bandages” that would use electrical currents to help heal wounds by improving and directing the flow of cells in tissue regeneration.

“These data clearly demonstrate that the kind of cellular control we would need for a smart bandage might be possible, and the next part of our work will focus on adapting this technology for use in actual injuries,” said Cohen.

This most recent research project grows out of a larger, ongoing attempt by Maharbiz to develop smart bandages, which he claims could not only stimulate the healing process through directed tissue regeneration, but could also provide a way to monitor the progress of wounds while they heal.

“Right now, if you have a bandaged wound, the only way to tell its status is to remove the bandage and look,” Maharbiz said in an article published by The Center for Information Technology Research in the Interest of Society during one of his earlier projects.

By tracking the electrical activity of cells involved in the healing process, however, smart bandages could provide valuable information to doctors without the need to physically look at the wound. “It would help doctors gain control over how the healing takes place, more than just making it go fast,” Maharbiz said.

Image Credit: UC Berkeley