Spinal Cord Stimulation Proving Its Worth As An Opioid Alternative For Long-Term Treatment Of Chronic Pain

By Paul Desormeaux, Decision Resources Group

Many North Americans have heard about the ongoing prescription opioid epidemic and its association with growing heroin use. Deaths from drug overdoses have overtaken car crashes as the leading cause of death in the United States, with approximately 52,000 cases yearly — 33,000 of which involve prescription or illicit opioids.

One potential way to cut America’s dependency on opioids, while still treating patients struggling with chronic pain, is the use of spinal cord stimulation (SCS). For years, the U.S. healthcare system has ignored this alternative treatment option because of the high up-front cost of the procedure. While opioids are a quick fix to the very real problem of chronic pain, and the up-front costs of SCS far exceed the cost of an opioid prescription, SCS is a less dangerous and more effective treatment that will only become more clinically effective with further product improvements — ultimately rendering it a less expensive long-term solution than opioids.

It is unrealistic to believe that opioid prescriptions will be completely eliminated in the U.S. anytime soon. Opioids are simple to prescribe, negate the need for physicians to perform a complex procedure, and have negligible up-front costs to the healthcare system. Under the current system, doctors will always need to see patients quickly, and any doctor can prescribe an opioid. As a result, prescribing opioids is an easy approach for any physician treating chronic pain, so much so that the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recently published guidelines calling for primary care physicians to limit the total dose of opioids being prescribed, as well as the prescription duration.

There is limited data showing the long-term efficacy of opioid treatment for pain. In fact, there is a wealth of data showing exactly the opposite. So, while opioids likely are here to stay, there is a broad movement to push back on opiates even without the presence of a valid alternative. As a result, physicians are considering SCS as a potential alternative, even though it has traditionally been thought of as a riskier treatment. And, with the growing abundance of clinical data demonstrating the effectiveness of SCS, the medical community is starting to realize that the risks of this surgery are far less serious than those associated with long-term opioid dependence.

In fact, a study sponsored by St. Jude Medical has shown that, one year after SCS device implantation, 93 percent of the 5500 patients tested had lowered their daily dosage of opioid prescription, compared to the control group, who had their SCS systems removed. While further studies must be done to confirm this data, and to accurately predict the decrease in the cost of opioid abuse due to the availability and efficacy of SCS, this certainly is a good first step in demonstrating that SCS is a viable treatment alternative.

SCS Has Proven Safe And Effective, And The Technology Continues To Improve

SCS has been controversial because it is not well understood by either physicians or eligible patients. A brief explanation of the mechanisms of action may help shed some light on the safety and efficacy benefits of the technology. SCS works by sending a mild electric current to nerves in the spinal column to modify central nervous system nerve activity and alter the sensation of pain felt by the brain. It has a fundamentally different mechanism to that of opiates, which alter the chemical make-up of the brain by binding to the body’s naturally formed opioid receptors. These receptors control incredibly important bodily functions, including stress, depression, pain tolerance, appetite, and cardiac rhythms. When an unnatural amount of chemicals is bound to an opioid receptor, the body reacts by naturally producing fewer opioid receptors, which weakens the body’s ability to control the aforementioned body functions. Neurostimulation is neither chemical in nature nor does it impact the body’s natural long-term ability to fight pain. Moreover, there is no possible addiction associated with the treatment.

SCS is quickly becoming a first-line treatment for chronic back pain and post-surgical pain, and new technological developments continue to expand its indications and deliver a better patient experience. In 2016 alone, multiple companies launched FDA-approved SCS technologies that reduce the stimulation felt by patients during treatment, as well as more specialized technologies that target specific areas of the body.

The medical device company Nevro has developed a high-frequency stimulation system that has demonstrated successful delivery of pain treatment without any residual sensation, so that patients can go about their everyday lives without being hindered by the treatment. St. Jude Medical is the first company to receive FDA approval for dorsal root ganglion (DRG) stimulation. The DRG is a bundle of nerves at the base of a spinal nerve that physicians have discovered is responsible for pain management in some extremities. Clinical trials have shown that DRG stimulation can successfully target more specific pain treatment of the limbs, feet, and groin, which are areas that are much harder to treat with traditional SCS.

In addition to advances in traditional SCS technology, there is a new form of neurostimulation to treat chronic pain using stimulation of the peripheral nerve. Rather than being placed on the spinal column, peripheral nerve stimulation generators are placed just under the skin in an area near the pain. This leads to less invasive, more affordable, and more specific targeting of pain when compared to traditional SCS. With a lower price tag, peripheral nerve stimulation will also offer a lower-cost alternative to SCS for those with less insurance coverage.

SCS Treatment Provides A Cost Benefit For Patients Likely To Abuse Opioids.

SCS procedures are neither simple nor cheap. The average procedure cost for initial implantation of a pulse generator is over $20,000. Because of this, it can be very difficult for physicians and policy-makers to wrap their heads around the idea that this treatment is actually a less expensive alternative to long-term opioid treatment. However, a recent study by the Medical Care journal has estimated the cost of opioid overdose, abuse, and dependence in the United States alone to be $78.5 billion annually. This number is a combination of costs from healthcare and substance abuse programs, loss of productivity due to non-fatal doses, healthcare costs from fatal overdoses, and criminal justice-related costs.

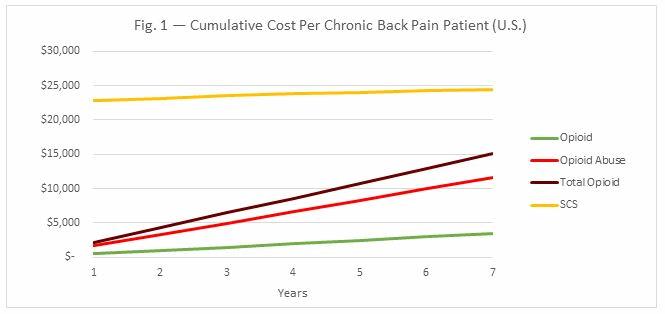

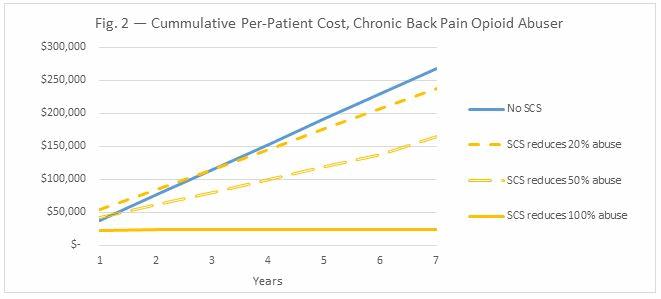

While neurostimulation serves as an expensive up-front cost for patients and insurance companies, costs to the nation’s healthcare system, stemming from long-term issues with the treatment, are negligible. Figs. 1 and 2 below break down the costs associated with SCS and opioid treatment in chronic back pain.

As Fig. 1 shows, even when the costs associated with opioid abuse are factored into the total treatment cost of chronic back pain, it is not cost-effective to treat every chronic back pain patient with SCS. However, SCS is a great option for patients who show early signs of opioid abuse. A number of predictors for abuse have been identified in recent studies, including chronic opioid use, younger age, alcohol abuse, abuse of non-opioid substances, receiving prescriptions from more than one doctor, and South or Midwest residence. Since patients take fewer opioid painkillers after being implanted with an SCS, they are less likely to abuse these drugs.

Moreover, SCS makes the most sense for chronic back pain patients who would otherwise require 7 years of opioid treatment or more. Since long-term opioid use is associated with abuse, and rechargeable SCS devices last at least seven years before they need to be replaced, it is more cost-effective for these patients to be treated with SCS than opioids. In sum, SCS is much more cost-effective when it is used to treat chronic pain patients among the two million Americans who abuse opioids annually, as it reduces the overall opioid abuse associated costs (Fig. 2). For chronic pain patients abusing opioids, even a 20-percent decrease in opioid abuse through SCS treatment reduces the overall costs of patient care.

SCS' Promising Future

While the overprescription and abuse of painkillers are legitimate concerns, chronic pain remains a major issue in North America. It is unfair to judge a patient burdened with chronic pain based on their decision to use highly addictive opiates, or a physician’s decision to prescribe them in order to help a patient. Additionally, for patients receiving short-term treatment, or those not at risk of dependence, SCS may not be feasible or cost-effective when compared to prescription medication for chronic pain treatment. Thus, the elimination of opioid treatment is nearly impossible.

Creating awareness and spending more money on neurostimulation will not save every future chronic pain patient from addiction, or completely eliminate the $78.5 billion dollars spent annually in the US on this epidemic. As a result, it should not be contended that opioids have no part in our healthcare system. Instead, the prospect of using a technology like SCS, which does not lead to substance abuse, should provide encouragement and incentive for scientists to continue improving upon such devices; for physicians to offer SCS despite its up-front cost; for companies to continue generating persuasive clinical data to better impact treatment and reimbursement pathways; for government to continue funding these efforts; and for payers to reevaluate the cost savings of SCS compared to the costs of long-term care due to opioid addiction. Adopting SCS to treat chronic pain as an alternative to opioids is not only sensible, but a necessary solution going forward.

About The Author

Paul Desormeaux is an Analyst at Decision Resources Group, where he covers markets related to neurology and endoscopy. He is the authority on neurostimulation, neurosurgery, and gastrointestinal endoscopy markets at DRG. Paul holds a B.Sc. from Queen’s University and a M.Sc. from Western University in biochemistry.