Wearable Concerns: Lifestyle vs. Medical-Grade Devices

By Doug Roe, Chief Editor

Today’s conservative estimates place the U.S. wearables market at about $2 billion in annual sales. However, a report by Soreon Research predicts that number will explode to $41 billion in the next five years.

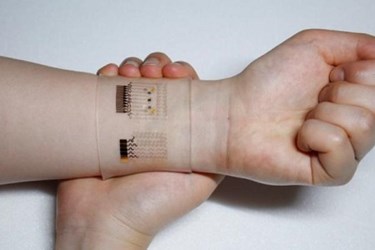

There are a lot of drivers affecting that potential boom – value-based healthcare, expanding availability of home health options, people playing a larger role in their preventive health choices, and advances in technology, to name a few. But, that growth has been accompanied by a rise in the number of non-healthcare companies entering the healthcare wearables market. Apple, Google, Samsung, and even Walmart are poised to become large players. Therein lies a potentially scary proposition — consumer electronics manufacturers’ convergence with healthcare providers.

In an address at the American Medical Association’s (AMA) annual meeting, CEO James Madara, MD, discussed the great advances in wearable technology as “remarkable tools.” But his thoughts on consumer wearables were harsh. “Appearing in disguise among these positive products are other digital so-called advancements that don’t have an appropriate evidence base (unregulated), or just don’t work well. They confuse patients, impede care, and waste our (physicians’) time.” He went on to call unregulated wearables “digital snake oil” and “quackery.”

Similar concerns are being presented in the Fitbit class action lawsuit. To be clear, the lawsuit does not challenge all of Fitbit’s product performance features — just the constant heart rate monitor, the PurePulse. In an independent study by researchers at the California State Polytechnic University, 43 subjects were tested wearing Fitbit devices containing the PurePulse heart monitor. Those results were compared to a time-synchronized electrocardiogram (ECG). The ECG measures electrical impulses of the heart, while the PurePulse uses an optical sensor that measures blood flow in the wrist. The tests found that the wearable devices were off by 20-30 beats per minute.

“This is a margin of error that is unacceptably high and dangerous, especially for people with high risk heart disease,” states the lawsuit. Fitbit — not the only consumer fitness device to have been accused of erroneous heart rate results — has refuted the claims. But the lawsuit ties back to Fitbit misrepresenting how accurate the devices are during physical activity, thus misleading consumers.

So, how is medtech to help consumers and physicians differentiate between medical-grade and lifestyle devices? I spoke to Waqaas Al-Siddiq, co-founder and CEO of Biotricity, a start-up healthcare company delivering medically relevant remote biometric monitoring solutions. Al-Siddiq shared his thoughts on this issue, and how his company has addressed them.

Med Device Online: Do you think this Fitbit situation — and the introduction of non-medical grade healthcare wearables, in general — creates additional challenges for the medical device industry?

Al-Siddiq: Yes, but I feel like [Fitbit is] getting unnecessary grief; they are in a separate market (lifestyle/fitness) that was not targeting at-risk patients. That said, I think what has happened certainly has shed light on the subject. If you really want to have an impact on healthcare, you need medically relevant devices.

That discussion has surfaced because of the bad press and some of the lawsuits. So that, I think, is a positive. It is bringing to light the divisions in the field. A year ago, people would say, “you are a small company, Fitbit is a billion-dollar company, how are going to compete?” We are not competing with Fitbit; we are competing in a completely different category.

It has really separated the marketplaces and provided clarity, so that is a positive aspect. But it has created a challenge for all wearables now. A lot of money was invested in a variety of wearables technologies, with the idea that people would readily accept them and each would be the next big thing but, because of the negative press surrounding a nonmedical-grade device, the industry opportunity really has been damaged.

For example, we now have to make people aware that Biotricity devices are not consumer wearables. Rather than our previous situation, where people thought that we were competing with Fitbit, now they think our technology is just like Fitbit’s.

We have good protection, though, because we are constantly discussing our product as medical grade (with doctors and hospitals), but a lot of the other wearables companies cannot. Most are trying to be the next FitBit, so they will suffer from the same issue. A lot of these companies are new, small startups. I don’t think many are going to survive. The existing, bigger companies should be able to pivot themselves and reposition their promotional messages to clarify and focus on the fitness market. To move into the medical market, most companies will need to acquire an established medical device company, as it is difficult to enter this market without having the in-house expertise.

MDO: AMA CEO James Madara has stated that doctors have great skepticism related to wearables. What approaches are needed to gain the confidence of physicians?

Al-Siddiq: Physicians are a complex group. Everything that a physician does balances on three key things. If you can deliver those, then you have their attention. The first is clinical value: What is the actual clinical value of the data being provided, from a care perspective? Next, what is the time it takes to absorb this information? Finally, what is the compensation, remuneration associated with it? All three need to line up really well for them to be interested.

MDO: Could you provide an example of suitable clinical value?

Al-Siddiq: If you take one of the various fitness trackers and you download the data and you provide it to a physician, it has little value to him. First, it is too much random data, and it will waste too much of his time to process. Second, because he sees its accuracy as insufficient, there is no clinical value to him.

You need to change that perception of the fitness tracker’s data. Consider a diabetic patient, for example.

If that patient uses a fitness tracker and it can produce a summary report that says that a patient walked or jogged every day for the last 30 days, the doctor still doesn’t want the specific data, but now he can put into the patient’s medical record that they are exercising every day. That is the clinical value, the piece that he wants, because beyond that, the data doesn’t actually provide any actionable information for him.

Combining the fitness tracker data with blood sugar level data collected by a glucometer yields an even richer summary: What are the best days, what are the worst days, what’s the average?

So, the clinical value piece really has to be understood, up front, in terms of what is the physician looking for and what would he use this data for. Then, provide him exactly what he needs, and make sure the time required is the bare minimum, because physicians need to see a certain number of patients an hour, and you cannot change that metric.

MDO: What are the wearables considerations related to physician compensation and reimbursement?

Al-Siddiq: There are two really important areas: patient volume and medical billing codes.

Doctors are trying to do the best for their patients, but again they need to see a certain number per hour, otherwise they can’t make their expected living. If they have one patient who has to sit with them for 45 minutes because the physician needs to process wearable result data, now they have to see even more patients per hour to close the volume gap.

Compound that concern by giving the physician something that is not relevant — lots of information with little value — and you have increased their time investment and reduced their compensation. They are not going to support it.

Doctors are paid on preapproved billing code systems for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. For example, today, using a home-based blood pressure monitor, a doctor can review its information and be compensated for his time. This is a recent change as the system shifts towards prevention. Historically, a doctor would have to redo that blood pressure test. If there is no compensation connected to the data provided, the doctor will order a test that has a billing code — a wearable may provide the same information, but by ordering the test, the doctor gets paid.

Medical-grade wearable manufacturers will gain faster acceptance by leveraging the existing payment models. As these devices become more widely embraced for home monitoring, and there are fewer patient visits to doctor’s office, this payment model may need to be reinvented.