A Holistic Approach To Your Medical Device's Usability

By Larry O. Blankenship, Boulder iQ

There’s no question that “intended use” and “indications for use” statements are critical to the successful design of any device. The statements are essential in getting the regulatory approval necessary to take a product to market. The information in them impacts patient safety, marketing, use, training in the field, and more.

Yet these statements are not enough to guarantee user acceptance and success once a device launches. In a competitive marketplace, developers must plan and design for what happens once their device leaves the manufacturing facility. They need to look at how a device will make the journey to its intended users, how those users will work with the device in day-to-day operations and, quite simply, the factors that will determine if they like using the device or not.

Developers who think ahead in this way can incorporate many market acceptance factors into their original design process. Not only will it result in happier users, greater market success, and more revenue, but it will cut down significantly on the need for redesign efforts after the device has been introduced on the market. Every device is different, every user is different, and it will never be possible to predict every situation, environment, or use scenario. But it is possible to anticipate many potential issues with some forethought. The results will be more than worth the time involved.

Designing for what happens once your device leaves the shipping dock may not be as difficult as it sounds. Most issues — or opportunities for better design — will fall into one of three categories: transit, cleaning and re-sterilization, and multiple users or user environments. No matter what type of device, every design and development professional can benefit from a solid understanding of how their device will move from point to point and who touches it once it ships.

Transit/Storage Once The Device Arrives At The Distribution Center Or Healthcare Facility

In most cases, even if the ultimate customer is an individual consumer, a device will go to some type of distribution center or healthcare facility. Upon arrival, a receiving agent usually will look for the packing slip, with confirmation that the facility ordered the item and that it satisfies an existing purchase order. The message to the manufacturer: In the development process, don’t overlook shipping documentation or treat it as an afterthought. Include its development as a stand-alone line item in the planning process. Make sure the documentation is complete, easy to find, and easy for the receiving agent to read.

From receiving, consider whether the device will go directly to an inventory or central supply room. In the case of a device headed to a healthcare facility, it may or may not have a stop or two on the way. For instance, a piece of electronic equipment that plugs into AC power — say, an IV pump — will usually be checked by the hospital’s biomedical engineering department to assure it has passed appropriate safety standard testing, and then it will be logged for maintenance purposes. In some cases, the receiving facility may test a device for safety and proper operation.

When your device is ready to move to a central supply storeroom, consider how it will travel, understanding that each facility may move equipment differently. Think about ease-of-use features that would bolster use and should be incorporated into the device’s design. In the case of a portable device like the IV pump, for example, some facilities may place it on a cart that rolls down an aisle or into an elevator. Others may have staff carry the pump by hand to the location where it will be used. Would a handle make that move easier and faster?

If elevator transportation is a good possibility, consider the scenarios that could affect the device’s reliability and functionality. What happens if it is an exterior elevator that moves equipment from the receiving dock? Is your device capable of withstanding rapid changes from outdoor to indoor temperatures? To illustrate, a manufacturer our company worked with found that its IV pumps were experiencing condensation inside the pumps before the cases were even opened. The problem was that a major hospital customer transported equipment on an exterior elevator with no heating or air conditioning. Sitting in the cold elevator shaft, then moving to interior 70-degree temperatures was the culprit. Redesign fixed the issue by coating all circuit boards with a waterproof lacquer. But a little up-front research into real-life transportation of the device may have prevented the problem and saved a great deal of time and money in the process.

Cleaning And Re-sterilization

Developers rarely think through the entire cleaning, disinfecting, and re-sterilization process for reusable devices, particularly for complex ones. Even though someone else will handle these processes, understanding how — and by whom — they’ll be handled could prevent major problems and redesign needs down the road.

For example, if you know that hospitals will be responsible for cleaning and re-sterilizing your device, take time early in the development process to do some research on what that sterilization equipment looks like and how it works. You may find differences between facilities, but chances are high that you’ll get good insight on basic parameters that could influence the design of your device.

In one case, a manufacturer ended up redesigning a surgical robot when it encountered a surprise in sterilization equipment. It wasn’t until clinical trials that the company discovered that hospital sterilizers could accommodate a maximum object length eight inches less than the size of the device. As a result, it had to spend substantial time and money in redesigning the device and suffered delays in bringing the device to market.

Multiple Users, Multiple Settings

The third category that med device developers often overlook is the day-to-day use of the device: how many users there will be and in what type of environments? Multiple users in multiple environments are not uncommon. Developers need to think about the intricacies of each use — and user — early in the design process to create a device that will garner market success.

In some cases, a device may be used both in healthcare and home settings. Building in functionalities to make the equipment easier to manage in both settings may be challenging but will pay off. Looking at an IV pump example again, users in an emergency room, operating room, or intensive care unit may appreciate modular pumps with a common control pump clamped to the IV pole. Conversely, when a patient goes home from the hospital with that pump, the IV pole usually goes, too. Figuring out a way to make the equipment easier to use – perhaps allowing the pump to sit on a bedside table or enabling the IV clamp to fold inside the pump housing – would make the equipment far more convenient to use.

Post-Shipping Use Flowchart

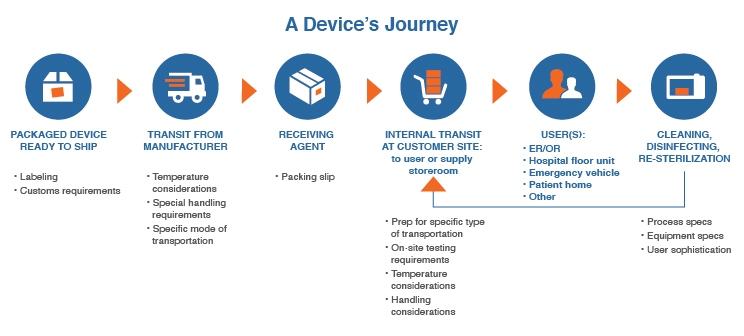

Detailing how a device will move from point to point, who touches it, and what will improve usability can feel like a time-consuming process at best and overwhelming at worst. Once you commit to including input on use beyond the shipping dock, the most efficient way to do so will be to create a post-shipping use flowchart, such as the one below.

Click on image to enlarge.

Keep the flowchart simple, and allocate time to create it early in the device definition and requirements process. Then make it a priority to incorporate the information as a guide in the design and engineering efforts of your device.

Conclusion

Getting your device to market as quickly as possible is critical. But speeding through the process to meet only the minimal regulatory requirements will produce suboptimal longer-term results. Take time up front to understand and design for how your device will move from point to point, who will touch it, and what will improve usability. In medical device development, there’s no room for “coulda, shoulda, woulda.” Get it right the first time to introduce a device that users will prefer because of its ease of use and the way it integrates into and interacts with the environment in which they will work with it.

About The Author:

Larry Blankenship is a director of Boulder iQ and has more than 30 years of experience in medical device product development, manufacturing, regulatory affairs, strategic management, and funding. He has helped multiple startups in the industry get products to market, working in management positions in divisions of Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and the Battelle Memorial Institute. Blankenship is a member of the advisory board at Colorado State University’s School of Biomedical Engineering and serves as a healthcare industry advisor to Blackstone Entrepreneur Network of Colorado. He can be reached at larry.blankenship@boulderiq.com or on LinkedIn.

Larry Blankenship is a director of Boulder iQ and has more than 30 years of experience in medical device product development, manufacturing, regulatory affairs, strategic management, and funding. He has helped multiple startups in the industry get products to market, working in management positions in divisions of Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and the Battelle Memorial Institute. Blankenship is a member of the advisory board at Colorado State University’s School of Biomedical Engineering and serves as a healthcare industry advisor to Blackstone Entrepreneur Network of Colorado. He can be reached at larry.blankenship@boulderiq.com or on LinkedIn.