Closing Quality System Gaps: 7 Steps To Properly Resource A Remediation Project

By Alan D. Greathouse, The FDA Group

A completed gap analysis is like a travel itinerary for your quality system. You know where you want to go, but you need a guide to show you where you are right now and which steps you’ll need to take to reach your destination.

Sometimes, gaps are simple and this itinerary writes itself. Other times, gaps point to more complex problems, requiring additional work to resolve. Either way, most quality teams have the tools they need to formulate the “directions” to their desired state, whether they tackle remediation themselves or work alongside a contracted specialist.

What isn’t so straightforward — and where many quality teams get stuck — is in bringing that remediation plan to life. Faced with competing priorities, teams often rush to turn their plans into projects while missing the important steps in between. Resource planning is chief among these oversights. In the interest of time, well-informed resource plans are traded for a set of snap assumptions that silently insert major risks into the project from day one — setting teams up for delays down the road when those assumptions are discovered to be flawed at the most inconvenient moments.

Unfortunately, this story usually ends the same way each time: blown budgets, extended timelines, and painful headaches for everyone involved. And it’s not unique to the life sciences industry. A 2017 survey by the Project Management Institute found that only 62 percent of organizations surveyed “always” or “often” use resource management to estimate and allocate their resources.

Ironically, the very same study showed that insufficient resource allocation is exactly what sometimes throws projects into peril. When asked about the primary causes of their past projects’ failures, nearly a quarter of the respondents cited “inadequate resource forecasting” and “resource dependency.” This is particularly frustrating, knowing that despite not being a top problem in project management, it’s one factor that can be tightly controlled from the start.

Yet, in the interest of saving time and getting projects underway as quickly as possible, teams often rely on ad-hoc resource allocation and a naively hopeful attitude about who is qualified and capable of bringing the plan to life. The importance of taking the time to do this critical planning is simple: Resource planning provides an informed, realistic view of what a team has versus what the project demands.

With so much riding on those responsible for carrying out the tasks of a project, we’ve developed an adaptable strategy for resource planning, specifically when setting out to close gaps following a system-wide assessment.

Before we jump in, though, a note about terminology here: While the word “resources” generally implies all of the things that a project manager or organization depends on to deliver products and services, we’re using it in this context to refer to human resources in particular. In truth, planning the people needed for a project is different from planning the material resources, so such a distinction is important.

In both cases, however, doing it right matters. Over-resourcing always wastes time and money and under-resourcing always risks missing critical milestones. Project managers need to understand what resources a project needs and what resources the project already has at its disposal before putting hard dates to any part of the plan.

1. Break the plan down into a task-focused project.

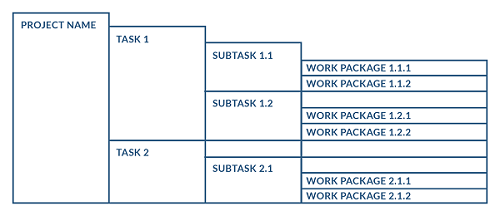

To kick off your resource planning, reorganize your plan — in whatever form it takes — into a series of tasks, subtasks, and discrete work packages that you can measure in man-hours. There are many techniques you can use to put workload estimates around a project, but specifically for remediation projects like this, a task decomposition (or work breakdown structure) is usually ideal. This should separate and categorize the components of your remediation plan into practical work orders at each step, giving you a visual representation of the project to know what specific resources you’ll need to allocate where and when.

The simplified example template below illustrates how this breakdown might look.

2. Estimate project task durations.

While there’s no way to precisely determine how long tasks will take, estimate the potential duration of each task using past experience, knowledge of experienced team members, or guidance from an external expert to inform your figures. The widely used Critical Path Method (CPM) project management methodology often lends itself well to these types of projects as it helps teams visually illustrate the project structure, set milestones, and calculate durations for tasks, including any interdependencies that exist. Using CPM or a similar methodology as a planning tool, you can roughly estimate the effort needed for each task involved.

3. Identify qualified internal resources and gauge their availability.

At this point, you should have a workable estimate of the scope of the project. Now it’s time to turn your attention to resources. Designate members of your internal project team and evaluate their skills and capabilities in relation to the tasks they will be assigned to. Make sure that these individuals are available for the time they’ll be needed. If you identify scheduling risks, mitigate them through a resourcing contingency plan. As in the previous step, use historical data from past projects to inform your estimates.

4. Add time for project management.

Before totaling your resource needs, be sure to account for the time project leaders will need to spend doing the work. In general, project management time should be at least an additional 15 percent on top of the task work. However, project leaders should exercise discretion based on the nature of the project.

5. Determine external resource needs.

As skills and competencies become associated with names, and names become associated with project tasks, you may find holes that need to be filled externally through a contracted resource. Put a red line around any areas where internal resources are either unqualified or otherwise unavailable due to scheduling conflicts. In each of these areas, consider a few critical questions to better understand what skills and experience are required in someone from outside your team:

- Which specific operations will they need to support?

- Which skills, capabilities, or experience are essential to ensuring those operations can be adequately supported?

- What specific requirements exist for the process, equipment, or project in question?

- What specific qualities, capabilities, or experience must a specialist have to satisfy these requirements? (For example, is previous sterile room experience critical?)

- What is the expectation for specialists in terms of protocol drafting and execution?

- What is the training or onboarding process required prior to gaining access to the internal documentation control system?

- Will the specialists be required to initiate and drive change controls?

- Which specifications are relevant to the project or program?

- What specific qualities, capabilities, or experience must a specialist have to perform a thorough review?

- Which training and onboarding activities will be needed for this specialist before they can begin work?

- Have you accounted for training and onboarding in your budget?

- Are project timelines realistic given the amount of time needed for training and onboarding?

6. Calculate the total effort, review your estimates, and adjust as necessary.

Once you’re confident that you’ve captured the effort needed for each task and have arrived at a total, you may find the estimate to seem obviously high or low. If something doesn’t seem right, go back and look for areas to make adjustments to your estimating assumptions to better reflect how a project will likely pan out. If the project sponsor thinks the estimate is too high, and you don’t feel comfortable defending it, you have more work to do. Make sure it seems reasonable to you and that you are prepared to defend it.

7. Bring it all together in a resource management plan.

Once you’re confident in your estimates, organize your figures into a resource management plan that makes all of this information useful for project leaders and those whose buy-in may be needed to secure any additional resources the project demands. A well-crafted resource management plan can help convince stakeholders to approve budgets by specifying the type of skilled people needed to complete a project and conveying other key details. Before implementing your project plan, modify and organize it to assign every individual project task to the appropriate person.

An effective resource plan should include details such as:

- Resource Identification: The type of resource and, once identified, their name, title, source (if contracted), and the assigned project team

- Roles and Responsibilities: The function(s) that the resources will perform for the project

- Resource Requirements: The relevant information about the resources available, including when they’re available, any conditions to that availability, and the duration of their availability

- Resource Cost: The direct or estimated resource cost (if contracted)

- Resource States: The current state of the resource, i.e., whether it’s planned, requested, approved, denied, allocated, or confirmed

- Resource Quantity: The amount of this type of resource (for example, the number of labor hours)

- Resource Locations: Where the resource is located, including virtual resources and co-located teams

- Resource Calendar: The scheduled working days, shift hours, start and end dates for different project milestones, and scheduled holidays

- Resource Issue Log: The information on resource planning challenges, for example, in acquiring skilled resources and problem-solving steps that worked to keep project resource plans on track

Conclusion

Despite the importance of proper resource planning in the initial phases of a quality system improvement project, such as one following a gap analysis, the steps involved are rarely as easy and straightforward as they might seem. Depending on the scope and complexity of the project, this can involve tough discussions about capital and capacity that are often under-addressed or avoided altogether.

Too often, teams rush into planning and executing quality system remediation without taking stock of the resources they have and comparing it against the resources the plan demands. Without this critical step, busy schedules, competing priorities, and mismatched skillsets can all converge to bring projects to a screeching and expensive halt.

Strategies like the one outlined here offer an example of how relatively simple structured strategies can go a long way in mitigating these risks, helping teams tackle critical improvement projects with confidence.

About the Author:

Alan D. Greathouse has over 15 years of GMP manufacturing experience focused on parenteral drug products. Throughout his career, he has focused on manufacturing processes optimization and identifying and correcting operational inefficiencies. He has experience in life science production supervision and has served as a lyophilization expert and principal pharmaceutical consultant. He currently oversees consulting and contract staffing operations as senior director of quality and service assurance at The FDA Group. Access his downloadable guide covering these and other gap analysis remediation insights here. He can be contacted via the online contact form at thefdagroup.com.