Computer Systems Validation Pitfalls, Part 4: Inattention To Details

By Allan Marinelli and Abhijit Menon

When work is not performed according to protocol instructions — by cutting corners on quality outputs with the focus on profit as the main driver or by creating unnecessary work that reduces efficiency – this can result in pharmaceutical, medical device, cell & gene therapy, and vaccine companies losing profits, efficiencies, and effectiveness. The reason is a lack of QA leadership and management/technical experience, among other poor management practices, coupled with the attitude that “Documentation is only documentation; get it done fast and let the regulatory inspectors catch us if they can find those quality deficiencies during Phase 1 of the capital project and our validation engineering clerks will correct them later”. Consequently, these attitudes can lead to at least 15 identified quality deficient performance output cases during the validation phases, as will be discussed in this four-part article series. See Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 of this series for previous discussions.1,2,3

In Part 4 of this article series, we will examine the following quality deficiency performance output cases that we observed:

- incomplete metadata upon generating a family approach deviation

- pre-approving protocols for execution using the rubber-stamping methodologies (previously mentioned in Part 2 for the execution phase)

- no support documentation to substantiate the metadata stipulated in the expected result section

- Final Report Issue Scenario 1: incorrectly documenting the wrong deviation numbers in the result section of the final report (identified wrong deviation numbers in the compiled results table)

- Final Report Issue Scenario 2: created an additional incorrect identification of deviation number upon post initial first QA review

- Final Report Issue Scenario 3: re-identified the initial wrong deviation number while identifying a nonexistent deviation number after a third QA review.

We’ll use real case studies to illustrate our points.

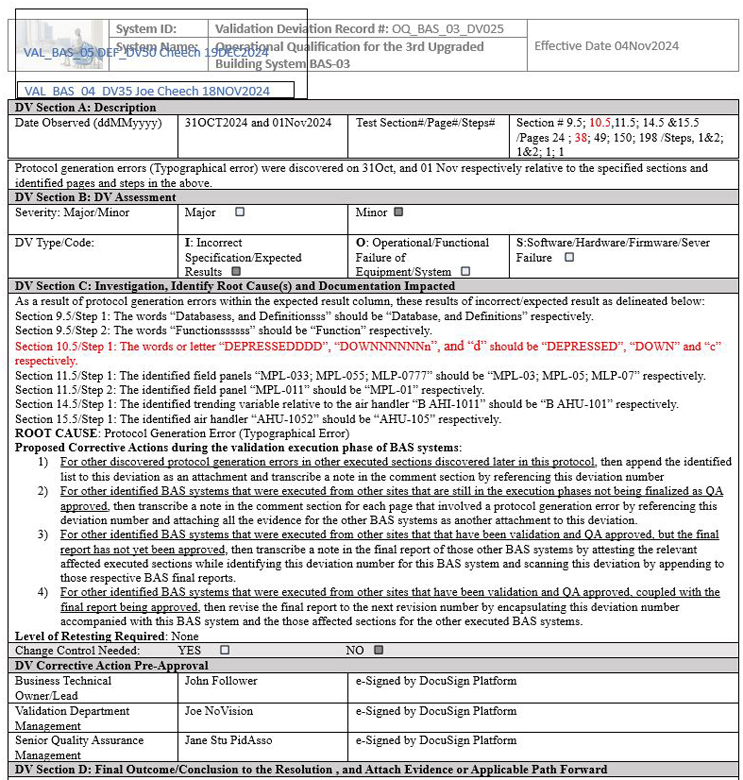

Incomplete Metadata Upon Generating A Family Approach Deviation

As a result of using the family approach per methodologies of Company ABC, any identical types of deviations identified in relation to their corresponding assets/systems and/or identified applicable sections of the protocol will be identified in one deviation, since they are associated with equivalent or identical intent of the deviation.

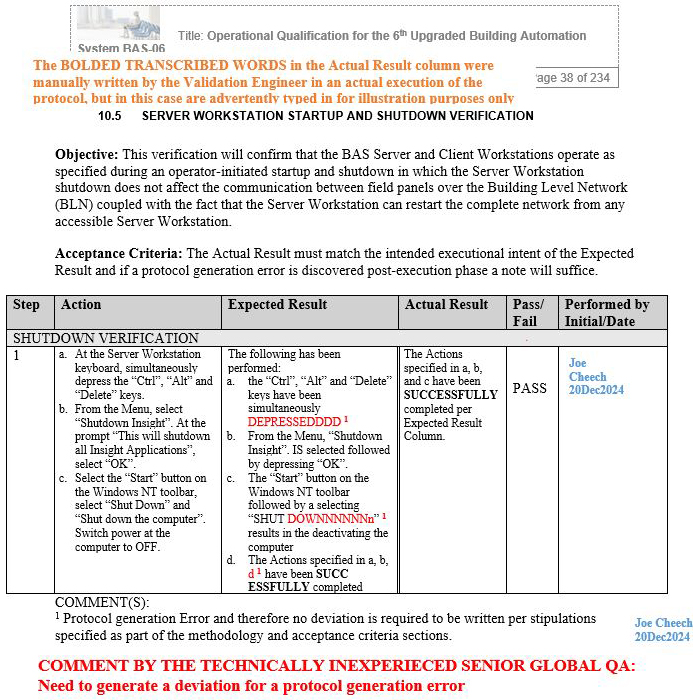

Even though the deviation indicated below should not have been introduced in the first place, since it was intrinsically allowed per protocols and directives to simply write a note (comment) at the bottom of the executed pages of any protocols, the technically inexperienced senior global QA insisted that a protocol generation error was required by all system owners to generate such deviation, as initially discussed in Part 3 of this article series.

In the case presented below in Figures 1 and 2, the initial deviation was written with respect to building automation system BAS-03, followed by the same information applicable to BAS-04 and BAS-05.

However, when the technically experienced senior QA performed a thorough detailed review of the execution protocol of BAS-06 that needed to adhere to the enforcements imposed by the technically inexperienced senior global QA from corporate, it was observed that the metadata of Section 10.5/Step 1 (shown in red) also was applicable to the deviation presented in Figure 1, but was missed by the technically inexperienced senior QA for BAS-03, BAS-04, and BAS-05.

One also can wonder, were there also any gaps in systems BAS-01 and BAS-02, despite the previous QA approvals of those entire executed protocols?

Moreover, this shows up not only as a gap but also as an inconsistency among the QA parties involved in approving. This can implicitly or explicitly indicate that there may be numerous other gaps among all other approved deviations for all GxP systems for Company ABC.

Figure 1: Screenshot 1: Incomplete metadata upon generating a family approach deviation

Figure 2: Screenshot 2: The words shown in red were not initially factored as affecting systems BAS-03, BAS-04, and BAS-05 as part of metadata upon generating a family approach deviation.

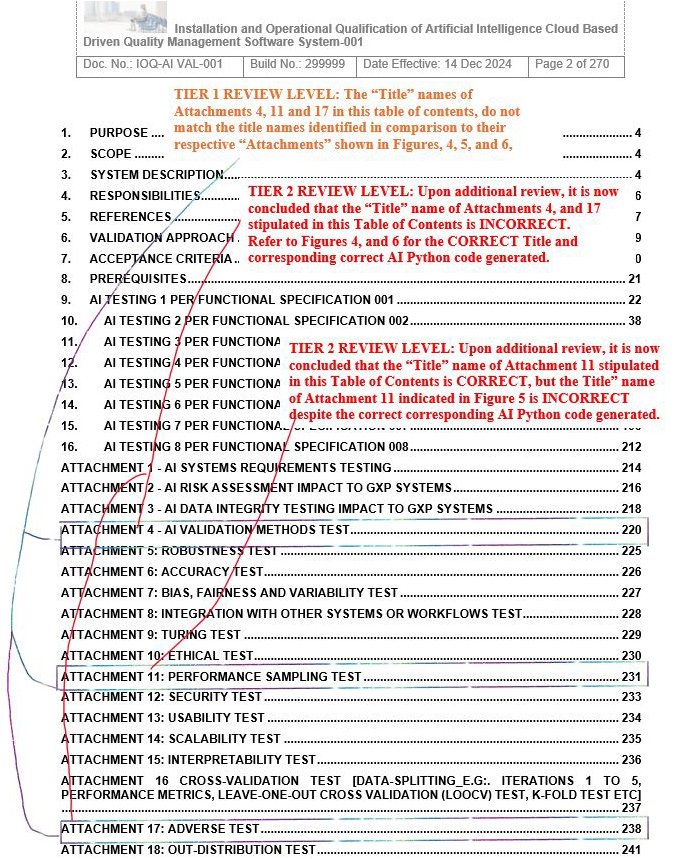

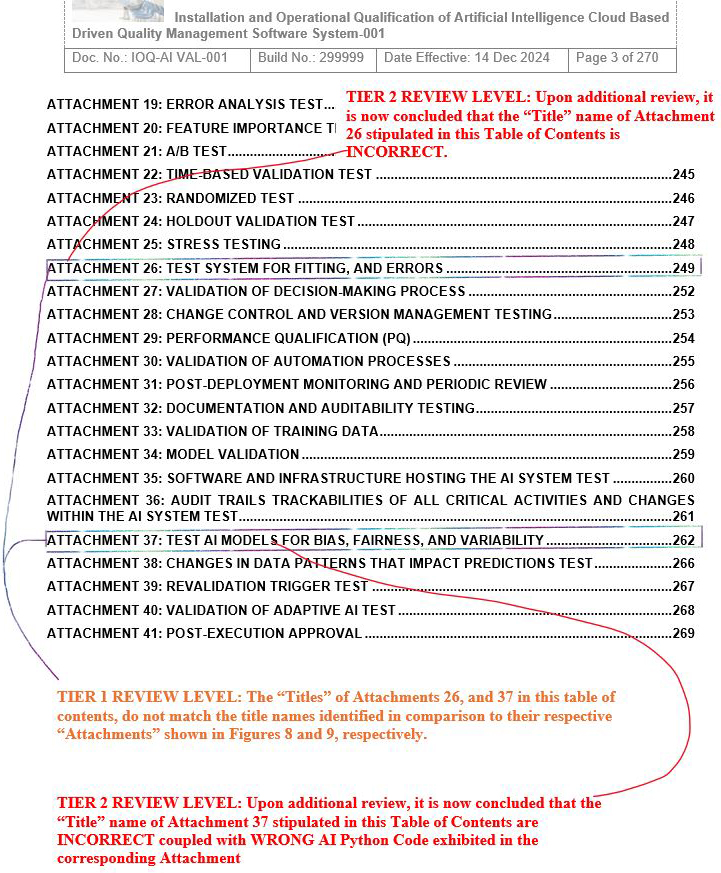

Pre-Approving Protocols For Execution Using The Rubber-Stamping Methodologies

As a result of the previous inexperienced technical senior QA and technically inexperienced senior global QA using the QA rubber-stamping approach, coupled with other QA gaps subsequently found by the technically experienced Senior QA, there are three quality gaps shown in scenarios 1 to 3 involving Tier 1 and Tier 2 review levels, as delineated below in Figures 3 to 10.

Figure 3: As part of a Tier 1 review level, it was observed that the Title Names indicated in this Table of Contents do not match the Title Names indicated in the actual attachments. See supplementary conclusions mentioned in all subsequent Figures 5 to 10 pertaining to a Tier 2 review level.

Figure 4: As part of a Tier 1 review level, it was observed that the Title Names indicated in this Table of Contents do not match the Title Names indicated in the actual attachments. See supplementary conclusions mentioned in all subsequent Figures 5 to 10 pertaining to a Tier 2 review level.

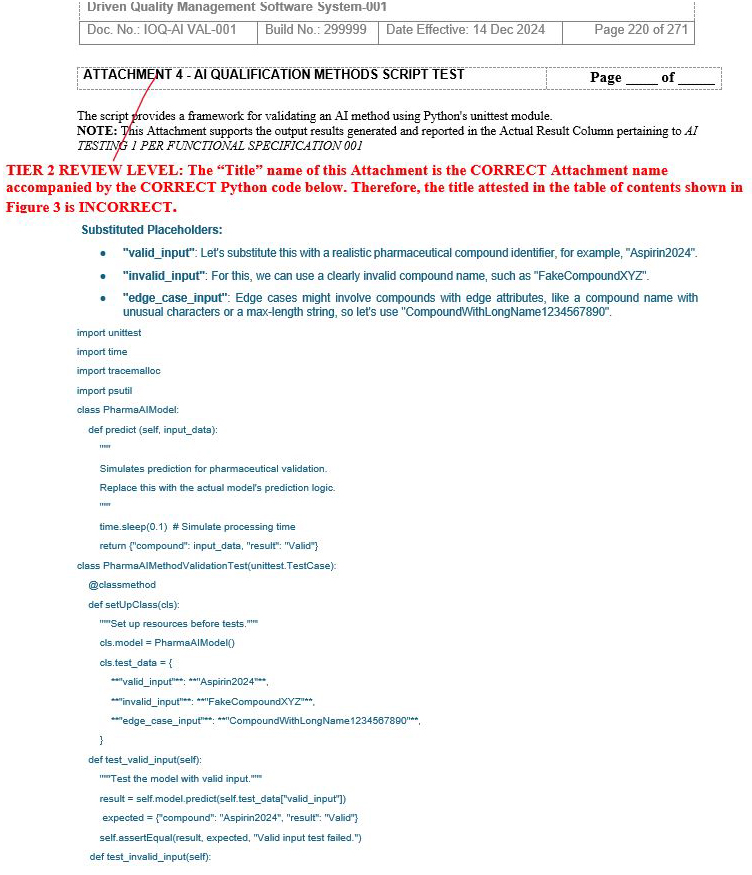

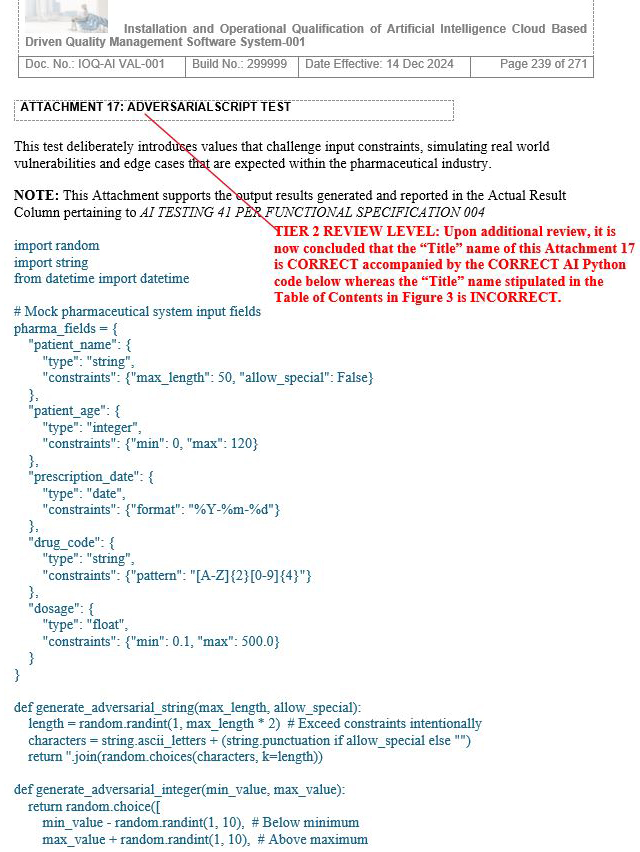

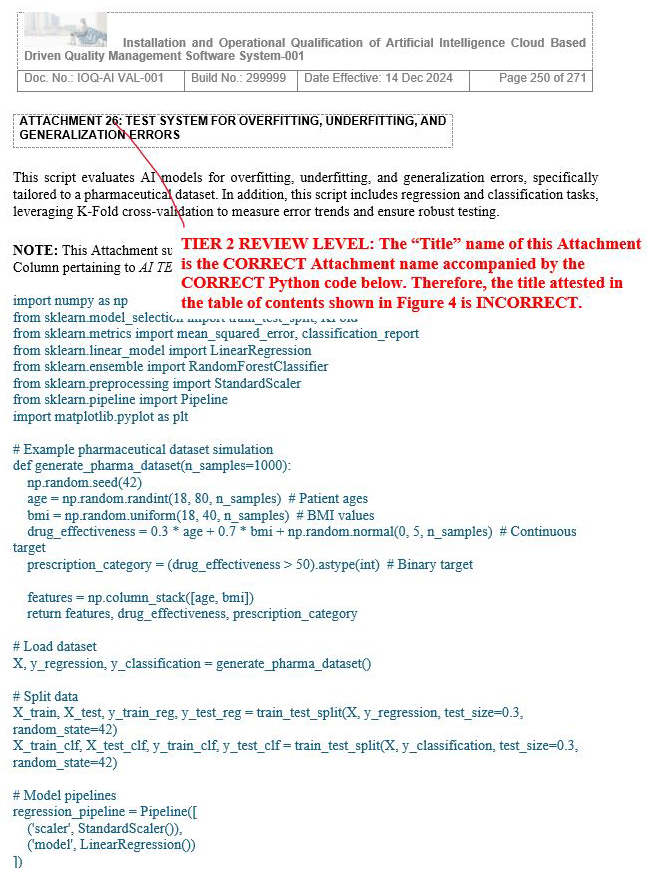

Scenario 1: Tier 2 Review Level: It was concluded that the Title Names indicated in the Table of Contents for Attachments 4, 17, and 26 are INCORRECT despite Description of the Test and CORRECT AI Python Code

Refer to Figures 5, 6 and 7.

Figure 5: Upon a Tier 2 review level, it was concluded that the Title Name, Description of the Test, and AI Python Code shown in this screenshot (Attachment 4) are CORRECT.

Figure 6: Upon a Tier 2 review level, it was concluded that the Title Name, Description of the Test, and AI Python Code shown in this screenshot (Attachment 17) are CORRECT.

Figure 7: Upon a Tier 2 review level, it was concluded that the Title Name, Description of the Test, and AI Python Code shown in this screenshot (Attachment 26) are CORRECT.

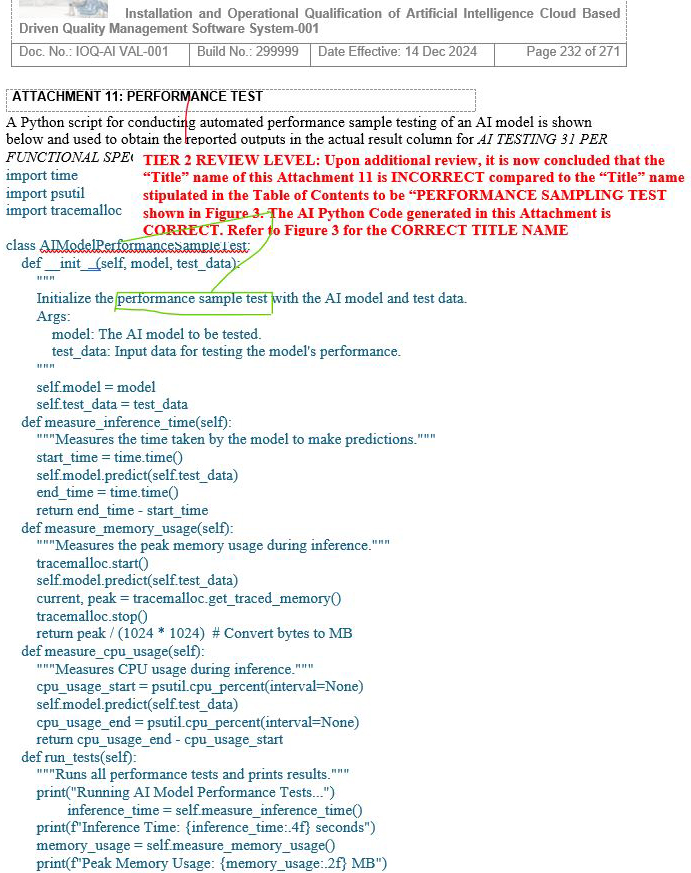

Scenario 2: Tier 2 Review Level: It was concluded that the Title Name indicated in the Table of Contents for Attachment 11 is CORRECT, with a CORRECT AI Python Code and Description of the Test exhibited in the actual Attachment 11

Refer to Figure 8.

Figure 8: Upon a Tier 2 review level, it was concluded that the Title Name Description of the Test is INCORRECT despite AI Python Code and Description of the Test shown in this screenshot being CORRECT. The title stipulated in the Table of Contents must match the actual attachment title names.

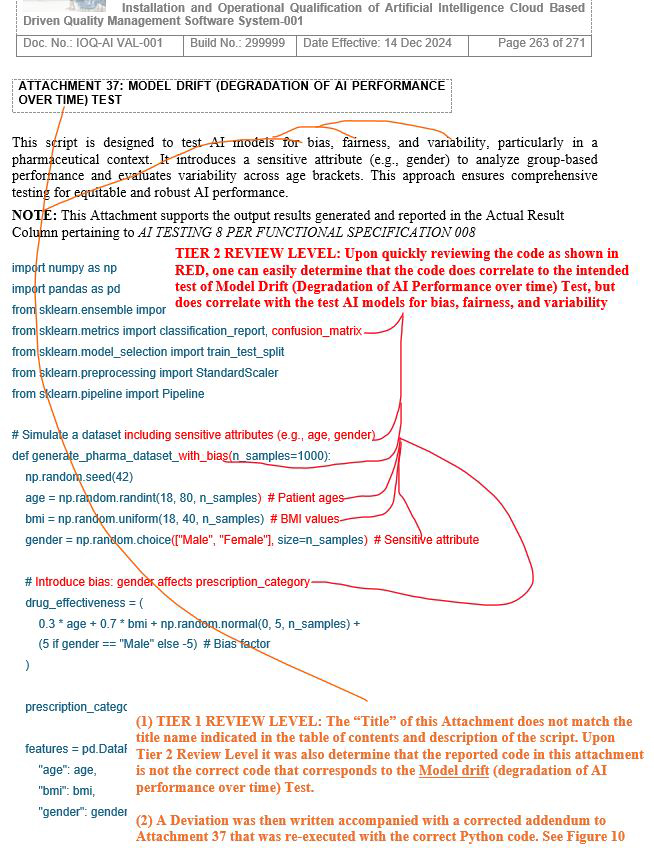

Scenario 3: Tier 2 Review Level: It was concluded that the Title Name indicated in the Table of Contents for Attachment 37 is INCORRECT, with an INCORRECT AI Python Code and Description of the Test exhibited in the actual Attachment 37

Refer to Figure 9.

Figure 9: Upon a Tier 2 review level, it was concluded that the Description of the Test and AI Python code shown in this screenshot (Attachment 37) are NOT CORRECT.

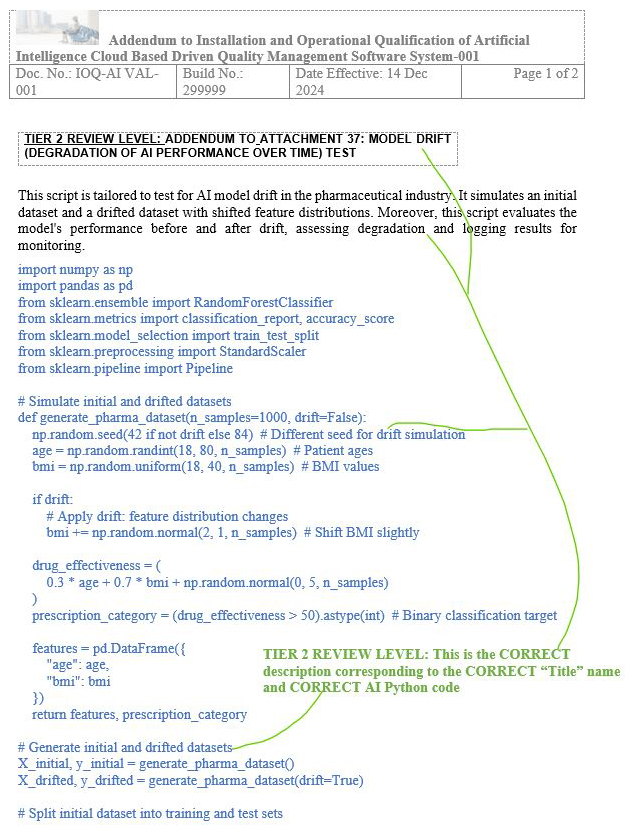

See the corrected AI Python code and corrected description shown in Figure 10 below, which was appended to the deviation.

Figure 10: The Title Name, Description of the Test, and AI Python code shown in this addendum to Attachment 37 screenshot are now all CORRECT and in alignment with the initial intent.

Solution

The post-execution phase (mentioned in Part 3 of this article series) or the pre-approval phase that has been clearly delineated in this section show that the list of identified gaps by the experienced technical senior QA were unfortunately previously approved as being acceptable by the inexperienced senior QA and the technically inexperienced senior global QA.

Any qualified QA involved in leading by example should never use the “rubber-stamping” approach with the sole aim of meeting often unrealistic schedules due to pressure from the other departments.

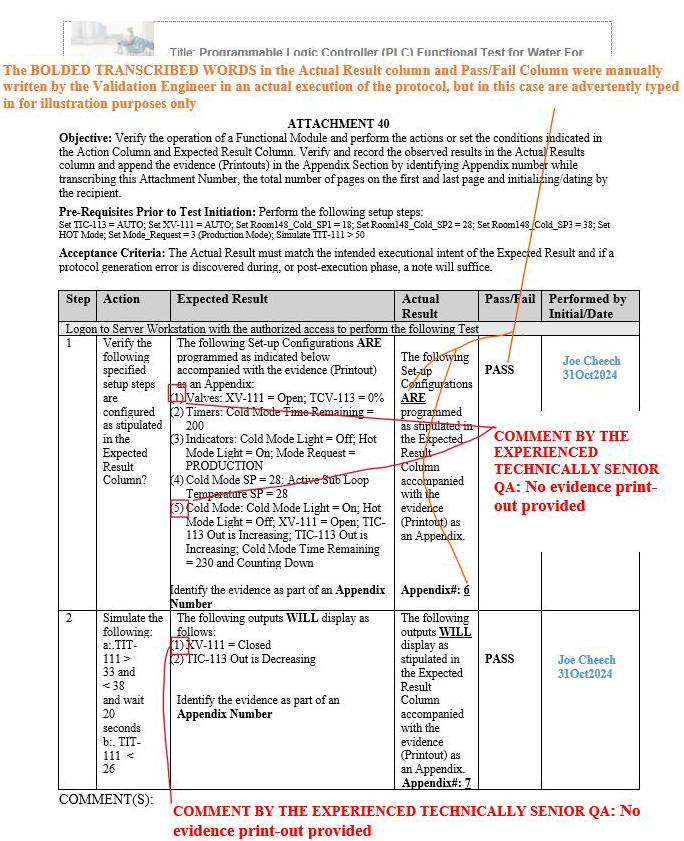

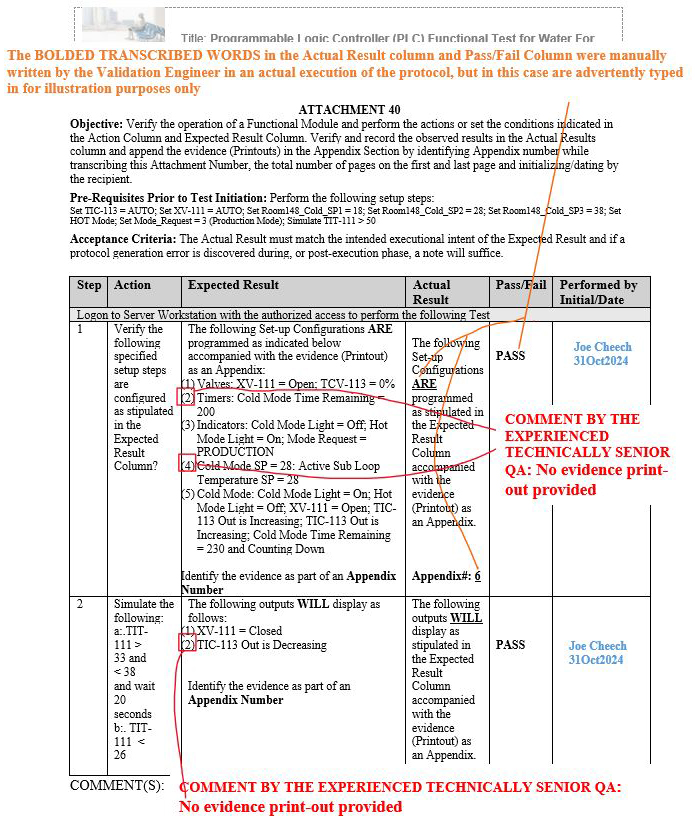

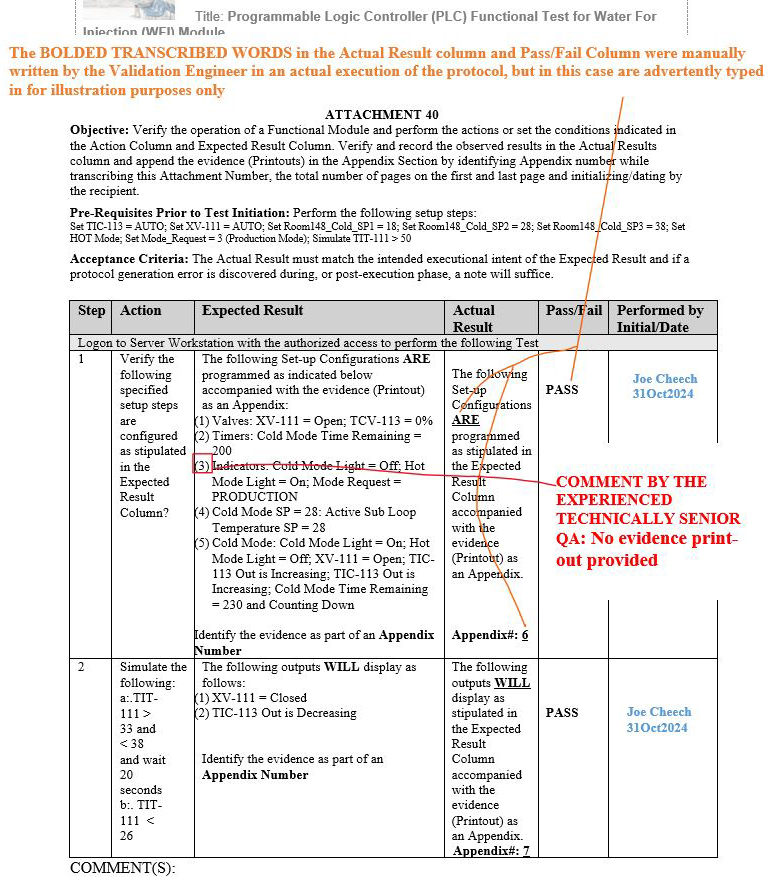

No Support Documentation To Substantiate The Metadata Stipulated In The Expected Result Section

Upon numerous QA reviews conducted by the experienced technical senior QA, it was observed as a gap pattern that the evidence (printouts) compiled and performed by numerous validation engineers during the execution phases included no evidence records for certain identified metadata shown in red (see the three scenarios in Figures 11 to 13 below) within the same step in the expected result column of the respective attachments.

Figure 11: Scenario 1: No evidence printout provided in the appendix for the specified parameters shown in red: Attachment 40, Programmable Logic Controller (PLC), Functional Test for Water For Injection (WFI) Module

Figure 12: Scenario 2: No evidence printout provided in the appendix for the specified parameters shown in red: Attachment 40, Programmable Logic Controller (PLC), Functional Test for Water For Injection (WFI) Module

Figure 13: Scenario 3: No evidence printout provided in the appendix for the specified parameters shown in red: Attachment 40, Programmable Logic Controller (PLC), Functional Test for Water For Injection (WFI) Module

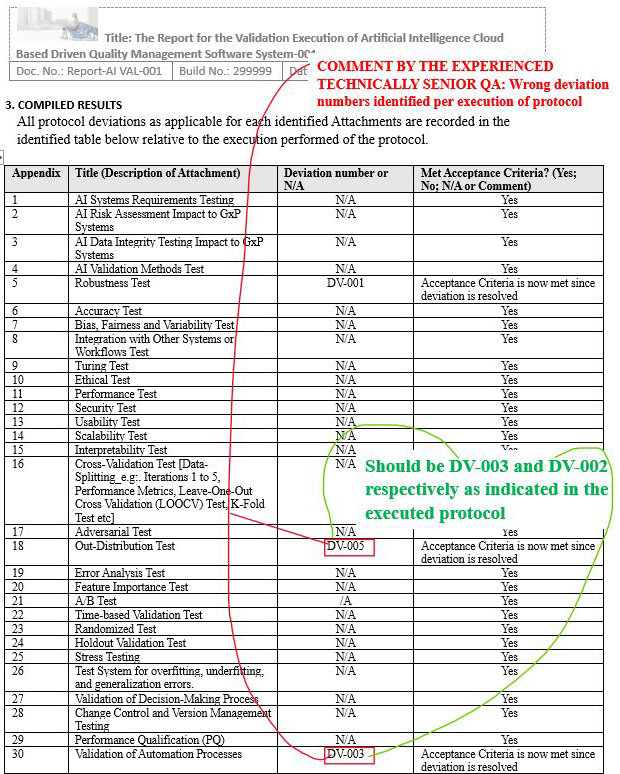

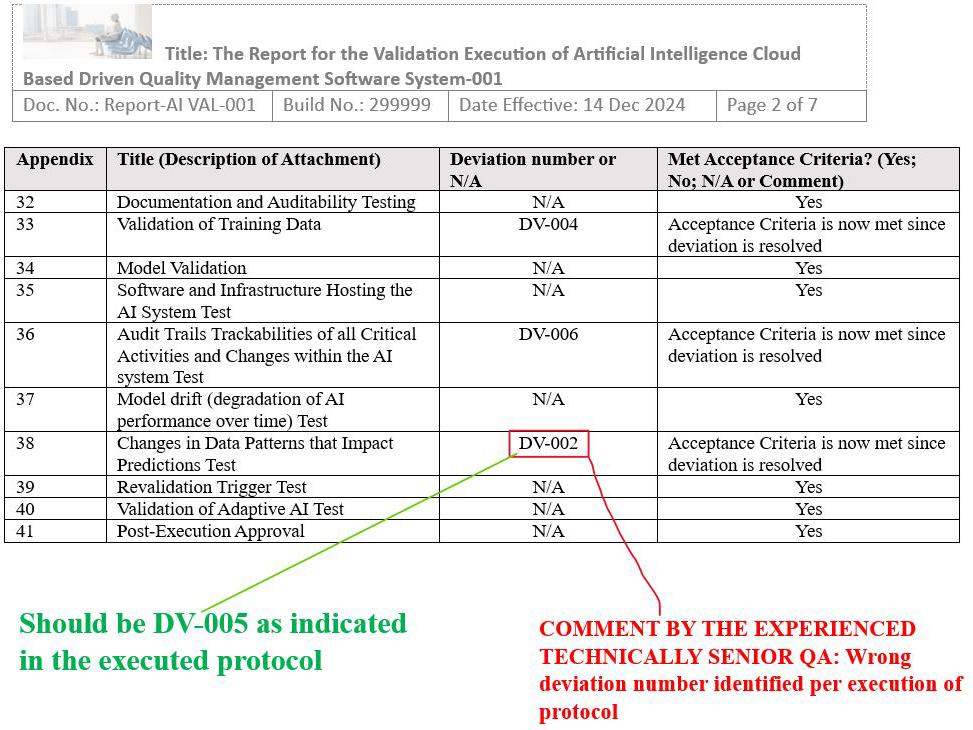

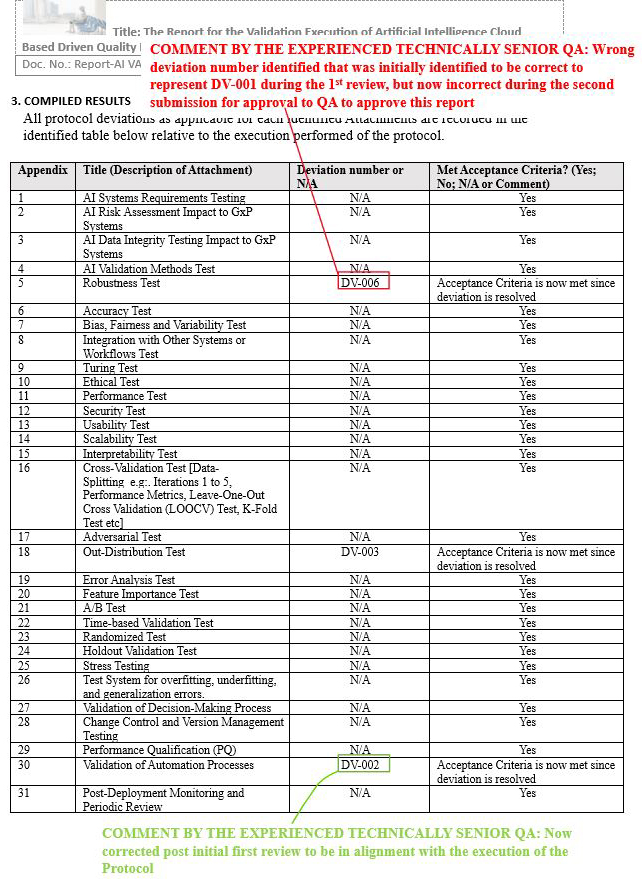

Numerous validation engineers indicated to the experienced technical senior QA that they were using tools such as Jira, Excel, Oracle Primavera P6, Google Sheets, or other tools that they put together to attempt to expedite the approval process of the final report, as opposed to taking the time to retrieve and review with understanding the corresponding executed protocol for alignment at hand while populating the final report accordingly.

This resulted in three final report issue scenarios that were submitted to QA toward final approval with at least three consecutive rejections as indicated below.

Final Report Issue Scenario 1: Incorrectly documenting the wrong deviation numbers in the result section of the final report (identified wrong deviation numbers in the compiled results table)

Figure 14: Scenario 1, Screenshot 1 of 2: Identified wrong deviation numbers in the compiled results table

Figure 15: Scenario 1, Screenshot 2 of 2: Identified wrong deviation numbers in the compiled results table

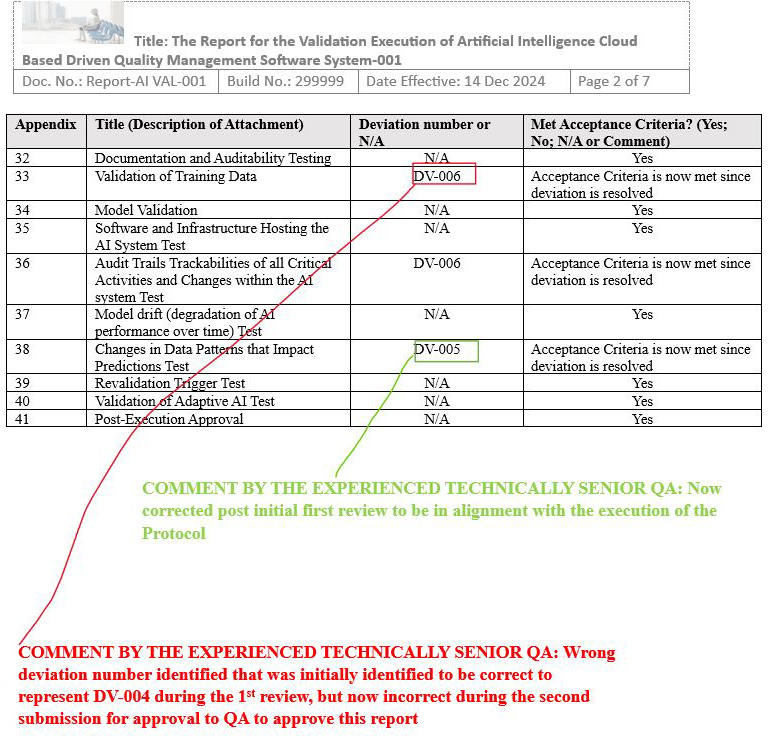

Final Report Issue Scenario 2: Created an additional incorrect identification of deviation number after initial QA review

Figure 16: Scenario 2, Screenshot 1 of 2: Created an additional incorrect identification of deviation number after initial QA review

Figure 17: Scenario 2 Screenshot 2 of 2: Created an additional incorrect identification of deviation number after initial QA review)

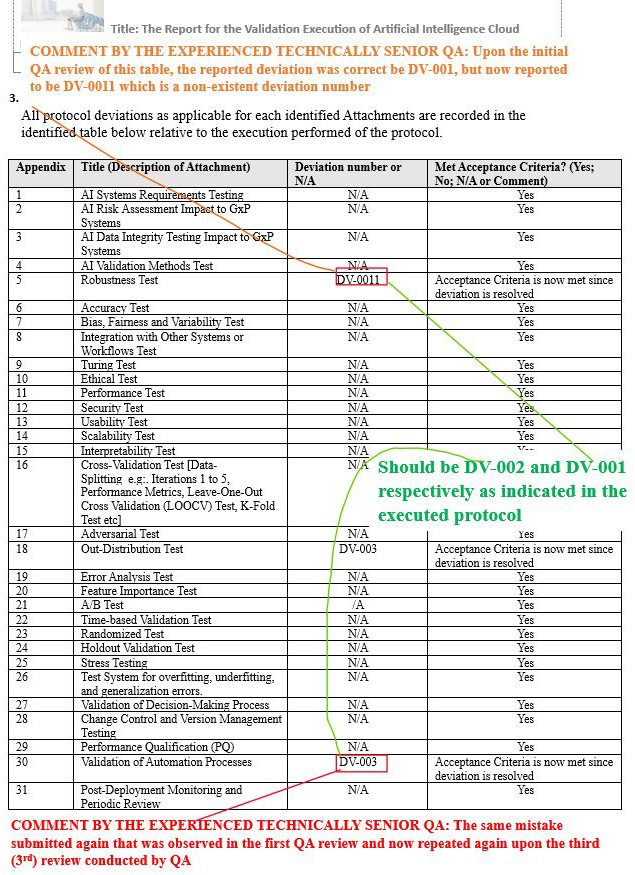

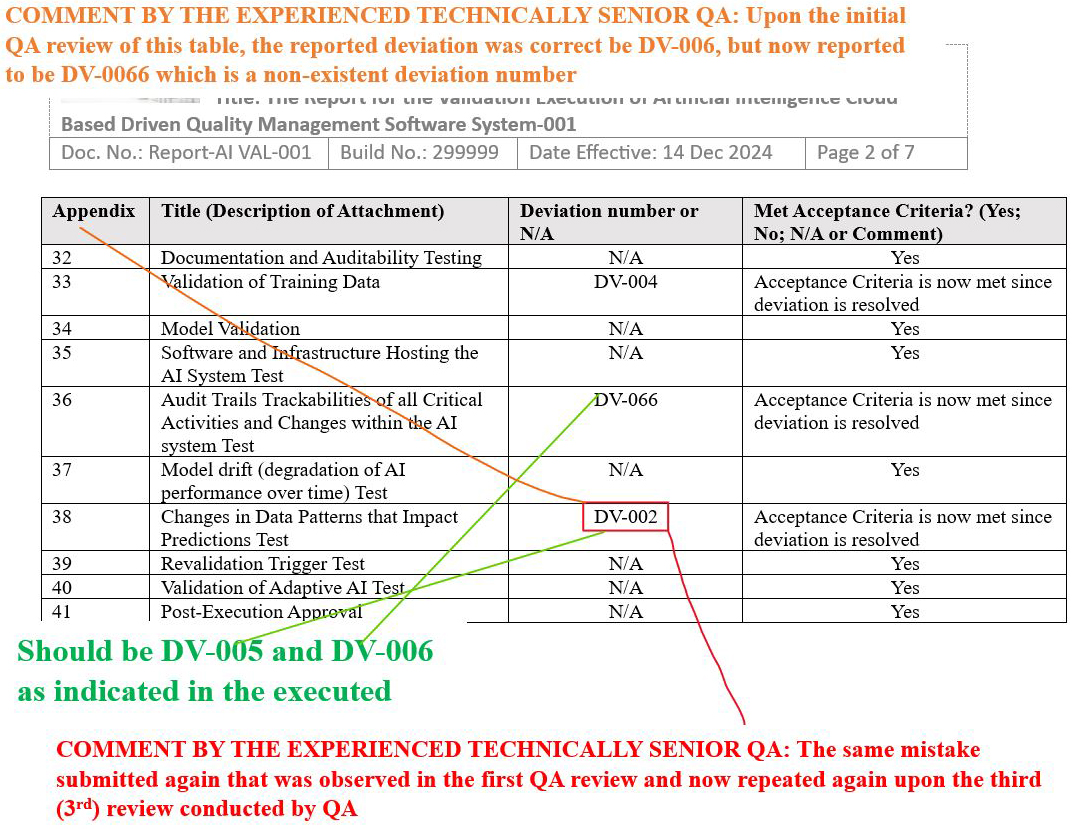

Final Report Issue Scenario 3: Re-identified the initial wrong deviation number while identifying a nonexistent deviation number after a third QA review

Figure 18: Scenario 3, Screenshot 1 of 2: Re-identified the initial wrong deviation number while identifying a nonexistent deviation number after a third QA review

Figure 19: Scenario 3, Screenshot 2 of 2: Re-identified the initial wrong deviation number while identifying a nonexistent deviation number after a third QA review

Conclusion

QA management needs to show by example great technical hands-on QA leadership over and above the typical QA duties. This holistically includes technically understanding from the ground up with hands-on experiences, commissioning qualifications validations (CQV), the computerized system validations(CSV), with respect to their associated manufacturing/laboratory systems (e.g., manufacturing execution systems [MES], Emerson DeltaV Distributed Control System, Syncade MES, AVEVA PI System, Valgenesis, Digital Validation with Vera, application lifecycle management software, product lifecycle management software, enterprise resource planning [Oracle/SAP], nuclear magnetic resonance, etc.), the software/system development life cycle (SDLC), good engineering practices (GEP), and quality by design (QbD). This includes the application of computer software assurance (CSA), GAMP 5 Edition 2, ISPE Good Engineering Practice Guide and using scientific risk-based approaches (e.g., ICH Q9, family approaches, agile models in software engineering adapted to be included as part of risk management, and understanding some level of programming coding, including current FDA regulations with respect to the applications of artificial intelligence/machine learning, etc.).

If QA management is deficient in acquiring hands-on technical QA leadership, this may result in your project undergoing at least 15 quality deficiencies discussed in this four-part article series. This could increase the probability that you will need to generate unnecessary repeat partial or full re-works in Phase 2 of your capital project pertaining to the identified gaps of the validation projects/activities performed in Phase 1, adding unnecessary expenses and losses on return on investments.

References

- Computer Systems Validation Pitfalls, Part 1: Methodology Violations

- Computer Systems Validation Pitfalls, Part 2: Misinterpretations & Inefficiencies

- Computer Systems Validation Pitfalls, Part 3: Execution Inconsistencies

About The Authors:

Allan Marinelli is the president of Quality Validation 360 Incorporated and has more than 25 years of experience within the pharmaceutical, medical device (Class 3), vaccine, and food/beverage industries. His cGMP experience has cultivated expertise from manufacturing/laboratory computerized systems validations, computer software assurance, information technology validation, quality assurance, engineering/operational systems validation, compliance, remediation, and other GxP validation roles controlled under FDA, EMA, and international regulations. His experience includes commissioning qualification validation (CQV); CAPA; change control; QA deviation; equipment, process, cleaning, and computer systems for both manufacturing and laboratory validations; artificial intelligence (AI)-driven embedded software and machine learning (ML); quality management systems; quality assurance management; project management; and strategies using the ASTM-E2500, GAMP 5 Edition 2, and ICH Q9 approaches. Marinelli has contributed to ISPE baseline GAMP and engineering manuals by providing comments/suggestions prior to ISPE formal publications.

Allan Marinelli is the president of Quality Validation 360 Incorporated and has more than 25 years of experience within the pharmaceutical, medical device (Class 3), vaccine, and food/beverage industries. His cGMP experience has cultivated expertise from manufacturing/laboratory computerized systems validations, computer software assurance, information technology validation, quality assurance, engineering/operational systems validation, compliance, remediation, and other GxP validation roles controlled under FDA, EMA, and international regulations. His experience includes commissioning qualification validation (CQV); CAPA; change control; QA deviation; equipment, process, cleaning, and computer systems for both manufacturing and laboratory validations; artificial intelligence (AI)-driven embedded software and machine learning (ML); quality management systems; quality assurance management; project management; and strategies using the ASTM-E2500, GAMP 5 Edition 2, and ICH Q9 approaches. Marinelli has contributed to ISPE baseline GAMP and engineering manuals by providing comments/suggestions prior to ISPE formal publications.

Abhijit Menon is a professional leader and manager in senior technology/computerized systems validation while consulting in industries of healthcare pharma/biotech, life sciences, medical devices, and regulated industries in alignment with computer software assurance methodologies for production and quality systems. He has demonstrated his experience in performing all facets of testing and validation including end-to-end integration testing, manual testing, automation testing, GUI testing, web testing, regression testing, user acceptance testing, functional testing, and unit testing as well as designing, drafting, reviewing, and approving change controls, project plans, and all of the accompanied software development lifecycle (SDLC) requirements.