Does Quality Even Matter? 10 Things Quality Departments Should Stop Doing Now

Senior quality leaders and the FDA agree quality organizations supporting pharma manufacturing often fall short of providing the support necessary to maintain and increase regulatory compliance and product quality. At the same time, some do not understand their actions and believe they are obstructionist and reflective of a strict compliance mentality with little regard for the business and its success. What would cause business partners to look at quality in such a way?

Quality departments covering pharma manufacturing operations are chartered by federal regulation to be autonomous from the manufacturing operations they support. However, an effective quality organization works with manufacturing to improve quality and prevent repeat observations from FDA inspections.

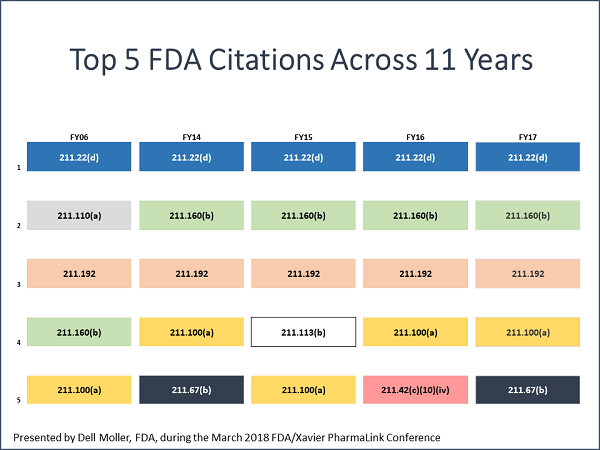

At the FDA/Xavier PharmaLink conference at Xavier University in Cincinnati in March 2018, Dell Moller and Nicholas Paulin presented the FDA’s top 10 drug GMP inspection citations for FY 2017 and participated in a panel discussion that provided insight into the observations. Moller is an FDA supervisory investigator based in Columbus, Ohio. Paulin is a drug specialist and pre-approval manager at the FDA’s Cincinnati district office.

“What we found,” Moller said, “was that the same citations are frequently observed from year to year on inspections. The ‘specifically’ or ‘for example’ may be different, but the root citation for these observations often remains the same. While major improvements have been made in industry over the years, we are seeing recurring themes.”(The top five are below.)

Lack Of Understanding Leads To Resistance

At the annual FDAnews Inspections Summit in late October in Bethesda, Maryland, Xavier Health director and former head of quality for Merck’s NC facility Marla Phillips shared her research on why pharma quality units are failing to meet their challenge and are viewed negatively within the organization in a presentation titled, “Why Quality Doesn’t Matter.” Phillips has chaired a series of pharmaceutical and medical device conferences co-sponsored by the FDA for more than 10 years and has participated in and co-led a number of agency-sponsored initiatives.

“The quality department owns a term that is met with resistance,” Phillips said. “It is viewed as a barrier by cross-functional partners.”

Part of the problem, Phillips said, is that there is no single, consistent definition of quality. “The quality department owns a term that is not easily defined or understood. Different stakeholders internally and externally have different interpretations.” Here is how some of those in a manufacturing organization define quality:

- Reliable/consistent product

- Product cures the patient

- No patient harm

- Product is always available

- Fewer failures

- More efficient process

- Product meets specifications

- .State-of-the-art facility

- Trained and educated employees

- Greatest value for the lowest cost

“Without a common definition of quality, how can it be increased? And what do we mean by increase? How can we gain cross-functional buy-in to something that is not defined? And if quality is not defined, how can cross-functional peers co-own it?” Phillips asked.

So in the end, does the quality function and/or quality really matter? “It doesn’t as the industry is operating today,” Phillips stated. “Quality today doesn’t matter because we can’t define what we own, we use fear tactics to influence, we measure the means detached from the end, and we don’t understand the business.”

Quality is often viewed as the function that checks on documents and other people’s work to ensure it complies with the governing SOPs and regulations. Phillips said it is not natural to check the details of another’s work or have one’s work checked in detail by someone else.

”The human brain is built for efficiency. It is not built for traditional quality functions, which demand that we pay attention to every single detail,” Phillips said. She provided the following illustration:

Most people with a good command of the written English language have no trouble reading this, even though every word longer than three letters is misspelled. While attention to written detail and proofreading skills can be taught, it is not the natural way most human brains generally work. Based on this, it is imperative that we develop innovative systems and processes that minimize the potential for and impact of human variability.

Quality Leaders Convene To Address Needed Changes

In an effort to address what appear to be systemic issues across quality departments, Phillips has engaged a multinational group composed of the chief quality officers (CQOs) from pharma, device, animal health, and consumer goods companies. While CQO may not be an official job title, the individuals are the most-senior quality executives in the company (see figure below). The multinational, cross-industry composition of quality leaders is consciously designed to get the most thorough, in-depth thinking and solutions from industries where quality departments operate similarly.

The team’s purpose is to “collaborate on leading-edge solutions that drive the future of the industry with and for all stakeholders.” It plans to “redesign the field of quality in a way that maximizes the value of the company for all stakeholders.”

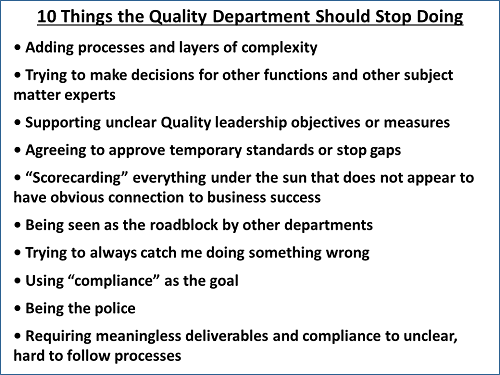

One of the group’s first actions was to interview their firm’s CEO and cross-functional business partners and ask a series of questions, including:

- What should quality stop doing?

- What should quality start doing?

- If your company did not have a quality department, how would it ensure quality?

After the feedback was pulled together, the Xavier team had closed-door meetings with the FDA, Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), and Health Canada to discuss the approach the team is taking to redesign quality. All three of the agencies were engaged in productive discussion about the possibilities for the “role of quality in the 21st century” and gave positive input on the effort and the direction it is taking. “We all recognize it is time for a change in how quality operates — regulators and industry alike,” Phillips commented. “This is the only way to break the cycle of repeat failures.”

“Historically it has been viewed as a conflict of interest for quality to talk about financial impact or business success” Phillips said. “I think in recent years we are seeing that soften up quite a bit, even from regulators, who recognize that if the business is not successful, it will have stock-outs and drug shortages, as well as other failures. If you have good, solid quality, it should be running your business systems in a very effective way. The natural outcome is going to be compliance, rather than a focus just on compliance, because everything will fail if the focus is just on complying.”

A focus on compliance is a central theme in the answers to the question regarding what quality should stop doing, which are shown below, in no particular order.

During her presentation, Phillips asked, “Would you say to your cross-functional peer, ‘You really need to close that investigation in 30 days? If not, we are going to have 483s and we could have enforcement action.’ A lot of quality people feel that is the ‘why’ — if you do not do these things, then this is what is going to happen. That is not the ‘why,’ that is the outcome. The ‘why’ is because it will keep your operation running so we can get the product to the patients who need it.”

She explained that a better understanding of internal and external stakeholders, their needs, and the language they use will be fundamental to redesigning the role of quality. “We need to shift the way quality is communicating if they want to get buy-in, and also to be sure they understand this is part of the problem.”

A future article will further examine stakeholder engagement, how quality can become a better business partner, the importance of language, and the efforts of the CQO team. Portions of the CQO team will convene for discussion, input, and networking at the FDA/Xavier PharmaLink pharma conference in March 2019 and at the FDA/Xavier MedCon medical device conference in April/May 2019.

About The Author:

Jerry Chapman is a GMP consultant with nearly 40 years of experience in the pharmaceutical industry. His experience includes numerous positions in development, manufacturing, and quality at the plant, site, and corporate levels. He designed and implemented a comprehensive “GMP Intelligence” process at Eli Lilly and again as a consultant at a top-five animal health firm. Chapman served as senior editor at International Pharmaceutical Quality for six years and now consults on GMP intelligence and quality knowledge management and is a freelance writer. You can contact him via email, visit his website, or connect with him on LinkedIn.