Does the Humanitarian Device Exemption Process Work (And Is It Worth Pursuing)?

By Janice Hogan, Partner and Co-Director of the FDA/Medical Device Practice, Hogan Lovells US LLP

The Humanitarian Device Exemption (HDE) pathway was created by Congress in 1990 to encourage the development of and facilitate access to devices for the treatment of rare conditions and diseases.

FDA guidance on the HDE process provides that a product may be designated a humanitarian use device (HUD) eligible for HDE approval if it is intended to benefit patients in the treatment or diagnosis of “a disease or condition that affects or is manifested in fewer than 4,000 individuals in the United States per year.” While an HDE application is similar in form and content to a premarket approval (PMA) application, it is designed to afford a lower threshold for approval. For an HDE, approval is based on a reasonable assurance of safety and probable benefit — rather than the safety and effectiveness standard for PMA approval — in recognition of the special considerations for rare diseases, including the lack of satisfactory alternative forms of treatment.

Like the corresponding provisions of the Orphan Drug Act, the HDE process was designed to provide incentives for development of therapies for rare conditions or diseases, recognizing that the small size of the target population could otherwise create an economic disincentive to product development. However, unlike the Orphan Drug Act, the HDE process has stimulated the development and approval of relatively few products since its inception.

FDA reports that the Orphan Drug program has resulted in “development and marketing of more than 400 drugs and biologic products for rare diseases since 1983. In contrast, fewer than 10 such products supported by industry came to market between 1973 and 1983.” By comparison, only 56 devices have been approved via the HDE mechanism since 1990. While this difference may in part reflect the availability of alternative device approval pathways or greater drug development activity, these factors alone likely do not account for the much lower usage of the HDE mechanism compared to the Orphan Drug program.

In part, this difference between the Orphan Drug and HDE mechanisms was by design. When enacted, the HDE provisions set a low threshold for eligibility — 4,000 patients per year — compared to the Orphan Drug Program, which has a corresponding threshold of 200,000 patients per year. The small population allowed for HUD designation is due not only to inherent differences between drug and device, it was motivated in part by an attempt to prevent perceived abuses of the Orphan Drug program. The HDE provisions also originally prohibited a profit on humanitarian devices, although it allowed companies to recoup research and development and distribution costs. This also was intended to prevent some of the perceived problems with the Orphan Drug program, including the high prices for many orphan products.

However, as a result of these stringent limitations, the HDE program had a limited effect. Congress has made multiple changes to the law to improve the HDE process, including an allowance for profit to be made, first on HDEs for pediatric populations, and more recently for adult-use HDEs. Despite these efforts, use of the HDE process remains limited, and there is evidence that increasing review times in recent years may be creating new barriers to use of the process.

HDE Application Volume Remains Low

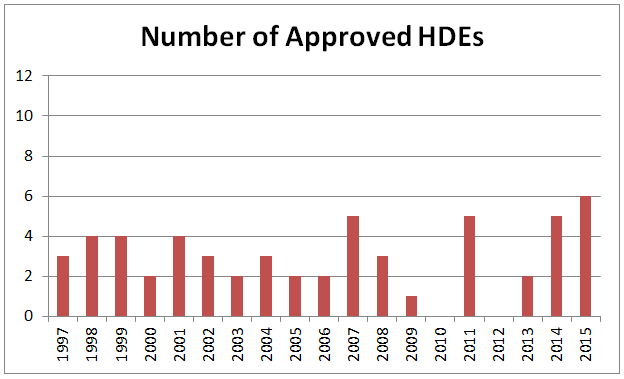

Over the history of the HDE program, since the first approval in 1997, the volume of submissions has remained low, and often dipped below three submissions annually. In recent years, the number of HDEs has been higher, with 2014 (5) and 2015 (6) both yielding among the highest-ever numbers of HDE approvals. Still, the low number of approvals indicates that, despite efforts to make the HDE process more attractive, its use remains limited.

Figure 1: Number Of Annual HDE Approvals, Since 1997

HDE Review Times Are Highly Variable, And Increasing

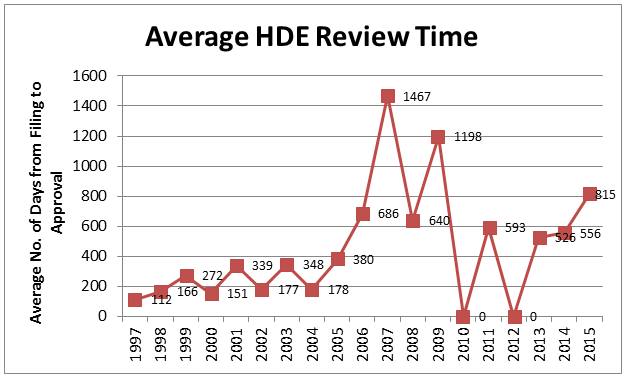

One factor that may contribute to infrequent use of the HDE process is regulatory burden. This can be measured, in part, by review time. As illustrated in Figure 2, during the first nine years of the HDE program (1997 to 2005), review time typically averaged from six to twelve months. However, in the past ten years, review times have more than doubled.

Figure 2: Average HDE Review Time, By Year

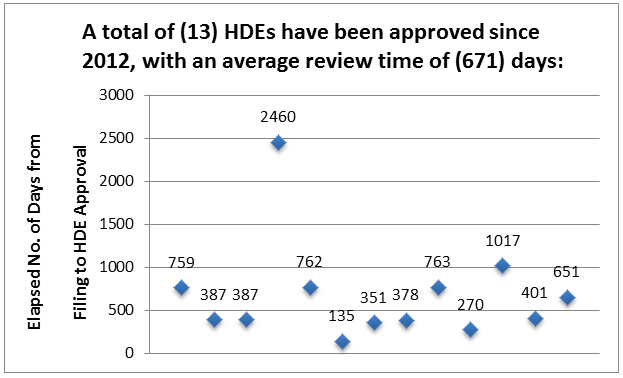

Since the most recent amendments to the law regarding HDEs (2012), a total of thirteen HDEs have been approved, with a mean review time of 671 days. The average review time for the six HDEs approved in 2015 was 815 days, more than 200 days longer than any of the preceding five years. This review time exceeds the average review time for PMA applications by a substantial margin, even though HDE applications are subject to a more liberal standard for approval. Only three of the recent HDEs were reviewed in less than twelve months, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Approval Time For HDEs, Since 2012

Furthermore, the above review times do not reflect the additional time required to obtain the initial HUD designation, prior to HDE submission. Although statistics are not publicly available on average HUD review time, this process can take significantly longer than the period specified by regulation, and it can take multiple rounds of review and/or resubmission to obtain HUD designation.

Use Of HDEs In Pediatrics

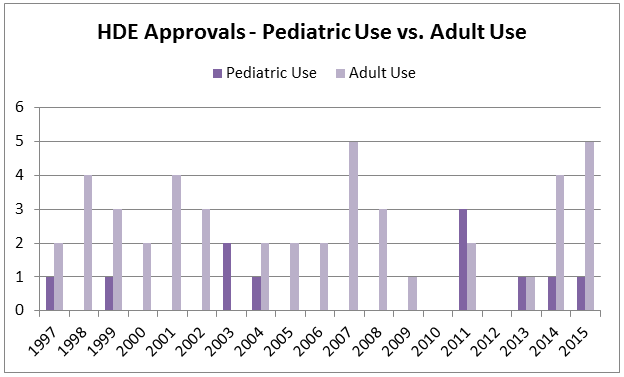

One of the populations intended to benefit from the HDE provisions was pediatric patients. Because devices for use in pediatrics may more often result in small populations, use of the HDE process for pediatric devices has been encouraged. However, over the history of the HDE program, only 11 pediatric devices have been approved by this mechanism. As noted above, in an effort to stimulate development, Congress first relaxed the profit limitation for HDEs intended for pediatric patients in the FDA Amendments Act of 2007 (FDAAA). However, this change in profit eligibility for pediatric humanitarian devices appears to have had limited effect, with only six new pediatric HDEs approved over the eight years since the change took effect.

In a 2011 report regarding pediatric device approvals, the GAO stated that “According to FDA, the agency received about one HUD request per year on average for devices intended to treat a disease that occurs in pediatric patients before FDAAA was enacted and about five requests per year on average in the years after the law was enacted. Likewise, FDA granted about one HUD designation for devices intended to treat a disease that occurs in pediatric patients per year prior to FDAAA and almost five such HUD designations per year in the years after.” However, despite the increased number of HUD designations for pediatric populations, few approvals have resulted.

Figure 4: HDE Approvals In Pediatrics vs. Adults, Since 1997

Use Of HDEs Varies Across Therapeutic Areas

Use of the HDE process also appears to vary significantly by therapeutic area, with relatively little use of the HDE process for diagnostic products (only five HDEs ever granted, compared to 51 for therapeutic products). This may be attributable to the relatively low test volume that would permit HDE designation. While development of an implant for a small population of 4,000 patients per year may be feasible in some circumstances, development of a test platform for very low test volume presents potentially less economic incentive. Despite these inherent differences, the threshold for HUD eligibility remains the same for both therapeutic and diagnostic products.

Additionally, nearly two-thirds the total number of HDEs approved have been in three therapeutic areas: cardiovascular, neurology, and gastroenterology. While this is, to some extent, proportionate to total volume of all types of submissions, some areas with high volumes of submissions show little use of the HDE process — such as orthopedics, ophthalmics, and general and plastic surgery. The reasons for these differences are not clear.

Figure 5: HDE Approvals By Therapeutic Area, Since 1997

Premarket And Postmarket HDE Requirements And Costs

Although the HDE process permits approval based on a finding of safety and probable benefit, clinical data generally is still required to support the approval process. A review of HDE approvals since 2012 shows a range in the amount of clinical data required to support HDE approval. While most recent submissions were supported by clinical studies of approximately 30 to 50 subjects, some submissions included as many as 200 subjects. Thus, there may be some variability in the interpretation and application of the “probable benefit” standard.

FDA approvals reflect greater flexibility in the type and amount of clinical data that can be used to support approval of an HDE compared to a PMA application, with greater use of single-arm studies, retrospective studies, and published literature. However, while the amount of data needed to support HDE approval is usually less than a PMA, the small patient populations often necessitate long periods of time to enroll and complete clinical testing.

In addition to the premarket requirements for HDE approval, there are also requirements that apply after an HDE is approved, including annual postmarket reporting and maintenance of IRB approval at all sites using the product. Maintaining the required records and reports further adds to the cost and regulatory complexity of HDE products.

Although some HDE-approved products are now eligible, in some circumstances, to charge a price that includes a profit, existing FDA guidance does not provide complete clarity on when a profit is permissible. The guidance states:

Except in certain circumstances, HUDs approved under an HDE cannot be sold for an amount that exceeds the costs of research and development, fabrication, and distribution of the device (i.e., for profit). Under section 520(m)(6)(A)(i) of the FD&C Act, as amended by FDASIA, a HUD is only eligible to be sold for profit after receiving HDE approval if the device meets the following criteria (for purposes of this guidance, “eligibility criteria”):

-

The device is intended for the treatment or diagnosis of a disease or condition that occurs in pediatric patients or in a pediatric subpopulation, and such device is labeled for use in pediatric patients or in a pediatric subpopulation in which the disease or condition occurs; or

-

The device is intended for the treatment or diagnosis of a disease or condition that does not occur in pediatric patients or that occurs in pediatric patients in such numbers that the development of the device for such patients is impossible, highly impracticable, or unsafe.

If an HDE-approved device does not meet either of the eligibility criteria, the device cannot be sold for profit.

Thus, humanitarian devices that are only for pediatrics are potentially eligible for profit, but the corresponding provision for non-pediatric HDEs is less clear. It appears based on FDA’s guidance to date that a humanitarian device suitable for use in both adult and pediatric patients would not be allowed to charge a price including profit, even though it still must satisfy the limitation on patient eligibility (less than 4,000 patients per year).

Conclusions

Key barriers to use of the HDE process include:

- Low threshold (4,000 patients/year) for HUD eligibility

- Difficulty in the HUD designation process

- Difficulty or delay in conducting clinical testing

- Long and unpredictable HDE review times

- Lack of clarity on ability to obtain a profit on HDEs after approval

- High cost and burden of maintaining HDE approval

In addition, while FDA in the past advocated use of the HDE process as a step toward broader future approval, the agency appears to have shifted away from this position in more recent guidance. FDA now requires strong evidence at the time of HUD designation to demonstrate that the product is not suitable for use in a broader population — based, for example, on its inherent design features, mechanism of action, or safety profile. Broader use of HDE-approved products outside the scope of the humanitarian designation have also, in some cases, led to withdrawal or enforcement action. These actions have likely further impacted manufacturers’ interest in pursuing HDE approval.

Finally, in addition to FDA considerations, reimbursement challenges for humanitarian products may further limit manufacturers’ willingness to pursue HDE approval.

Congress has attempted to refine the HDE program several times since its enactment, with amendments in the FDA Modernization Act (FDAMA) of 1997, in FDAAA of 2007, and in FDASIA of 2012. In addition, Congress is currently considering further modifications to the HDE process that could significantly improve its utility, such as an increase in the threshold for HUD designation from 4,000 to 8,000 patients per year.

The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), in a letter to Congress regarding the potential legislation, noted that “Other changes that could improve the process include efforts to expedite HDE review. In April 2015, in an effort to streamline reviews, FDA issued guidance on the Expedited Access Program (EAP), Expedited Access for Premarket Approval and De Novo Medical Devices Intended for Unmet Medical Need for Life Threatening or Irreversibly Debilitating Diseases or Conditions, which offers benefits to breakthrough products that are designed to address unmet medical needs. While HUDs are not addressed in FDA's EAP guidance, the agency has determined HUDs are not eligible for EAP designation. Still, given that the average review period for HDEs is even longer than PMAs, application of the EAP process to HDEs is warranted. Furthermore, because the HDE program is designed to foster development of products for rare disease where unmet medical need is clear, the objectives of the programs are complementary.

Further clarification of the circumstances in which HDEs can be priced in a manner that includes a profit would also help to foster product development, as would greater clarity on the circumstances in which HDE products can later progress to broader approvals. Without these modifications, and despite multiple Congressional efforts to date, use of the HDE process will likely remain limited for the foreseeable future.

About The Author

Janice Hogan is the director of Hogan Lovells' FDA/Medical Device practice. Janice focuses her practice primarily on the representation of medical device, pharmaceutical, and biological product manufacturers before the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

A biomedical engineer, she held positions in marketing/marketing research for a major pharmaceutical manufacturer prior to becoming an attorney. She has authored articles regarding the medical device 510(k) review process, regulation of medical software, orphan drug regulation, and medical device products liability, and a chapter of a textbook, Promotion of Biomedical Products (FDLI 2006).

Janice has served as an adjunct professor at the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia and as a guest lecturer at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, Drexel University, and Stanford University on the development and regulation of medical products. She is also a frequent lecturer at FDA regulatory law symposia and conferences on topics related to premarket approval of medical products, combination products regulation, and product development, and has served on the faculty of FDA's staff college training for new review staff.

Questions to the author may be directed to Janice.hogan@hoganlovells.com