Factors Undermining Your Lean Implementation (And How To Correct Them)

By Darren Dolcemascolo, senior partner and co-founder, EMS Consulting Group

Over nearly 20 years in the consulting industry, I have been involved in dozens of lean transformation efforts, many of them within the medical device industry. The majority of these were successful endeavors, but others achieved limited results. Each time I see a leadership failure lead to subpar results, I am compelled to think about it and write about it.

This article is about an organization that can best be described as a “rudderless ship.” Despite management’s desire to become lean, the company experienced constantly shifting priorities and multiple reorganizations over a one-year period.

I began working with this company because of a past client relationship with one of the C-level executives. He contacted me and requested a brief “lunch and learn” lean overview. Company directors and above also were invited to learn the Lean Improvement Model, and the basics of what it takes to transform an organization.

This overview was well-received, and the management team decided to pilot one high-volume value stream for improvement. They also identified one key individual to coordinate lean efforts in this initial phase. I thought this was a reasonable approach and agreed to provide facilitation support.

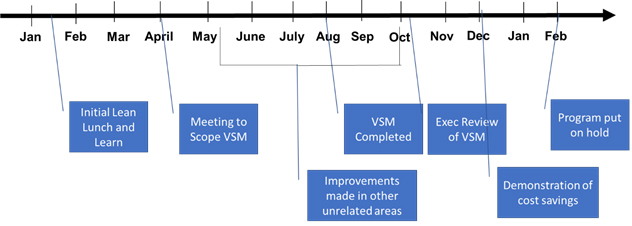

The selected value stream’s manager expressed interest in lean, a positive sign to me that the pilot would be successful. However, a session intended to scope the Value Stream Mapping (VSM) workshop had to be rescheduled multiple times before the team finally was able to meet and scope the project. This meeting took place about three months after the initial Lean “lunch and learn.”

The three-day workshop, which was scheduled approximately 30 days after the pre-workshop scoping meeting, was cancelled at the last minute because several team members had other, more important priorities. Instead, they asked if the event could be broken down into multiple meetings over time. While this approach could work, I was concerned with the level of commitment, I thought, “if this organization could not commit to a 3-Day workshop, could they commit the time and resources needed to implement improvements and create a daily management system to sustain and continuously improve?”

Despite my concerns, the team moved forward with a piecemeal approach to creating current and future state value stream maps showing dramatic improvements in lead time, processing time, and quality. The entire process took a few months to complete due to multiple cancellations and changes.

As the value stream maps were developed over a period of several months, the C-level executives grew impatient because they saw no results, and they asked their in-house lean coordinator to have our firm work with some other teams on a few problematic processes (which were outside the original value stream, but were “hot” issues at the time). We worked with those teams through an A3 problem-solving process.

The teams ultimately identified many small improvements but, by the time any improvements were implemented, the top managers were no longer interested, and had moved on to fight the next fire. This was frustrating to the teams making the improvements, and some of the improvements were not implemented due to the shift in priorities.

The original VSM team planned to present its VSM plan to the entire executive team and begin working on improvements. However, due to the executives’ availability, it took an additional 2 months to schedule a meeting to share the teams’ findings and recommendations. While the future state numbers looked impressive, the executives wanted to see the results happen quickly and calculate cost savings.

The results, the team explained, would happen over time, according to the plan. Each initiative identified in the VSM would have its own kaizen team and would utilize the A3 problem-solving approach. In fact, one of these initiatives already was in progress at the time, and some productivity gains were made and reported.

My assessment, at the time, was that the management team needed to demonstrate its commitment by:

- Ensuring the resources (team members) were available to work on the improvements.

- Holding the team leaders (who were primarily supervisors) accountable for the improvements and improved metrics.

I suggested the following approach:

- Engage several key team leaders (supervisors of key areas within the value stream) with A3 training and coaching, and have them lead the kaizen efforts. Our firm would provide the training and coaching, with the goal of developing problem-solving capability while making improvements to the value stream.

- Re-engage the management team to develop a strategy for lean and operational excellence throughout the organization.

The executive team did not want to commit to this approach until it showed a cost-savings. This was worrisome to me, as we had explained lean is not merely a “cost-cutting” initiative, but we continued to help the teams make improvements. Due to lack of resources, only some improvements were made by the end of the year — about 11 months after the initial “lunch and learn.” Working with the finance department and the lean coordinator, we were able to calculate a significant cost savings — in the $0.5M range — mostly due to additional capacity negating the need to hire as many people as previously planned.

Based on this initial success, and realizing there was so much untapped potential, we again suggested working with the executive team on strategy deployment with the goal of identifying a coherent plan, rather than jumping from one area to another for improvement. However, executives still showed no interest in pursuing a systematic strategy.

Shortly thereafter, several key middle managers and one of the C-level executives left the company, resulting in yet another reorganization. The lean coordinator was moved to a VP level, and lean efforts were put on hold indefinitely. The timeline below illustrates the events leading up to this.

What leadership lessons can we learn from this lean odyssey that ended prematurely? Consider these five lessons for management teams:

- Management commitment is crucial. Communicate your lean vision to the organization and let everyone know what his/her role will be.

- Don’t let too much time pass between the initial announcement/kickoff and actual improvement activity.

- Develop a plan utilizing strategy deployment and begin measuring key indicators. Don’t change the plan or reorganize at each sign of trouble. As you measure against your projected results, make adjustments, but don’t reverse course!

- Ensure you dedicate the resources, necessary for success. Training your people and allowing them to practice lean consistently will increase the likelihood of continued success.

- Engage every level of the organization to create a chain of accountability and support.

I have witnessed several organizations complete successful lean transformations, and the common thread among each is leadership behavior. For those leaders considering a lean transformation, or just getting started with one, I encourage you to reflect on the five lessons above before beginning your journey.