First-In-Human Studies - What's The Rush?

By Jon Speer, founder & VP of QA/RA, greenlight.guru

Any medical device initially starts with an idea — a problem to solve, with the hope of positively impacting human lives — and there are plenty of product development steps between inspiration and market launch. Today, medtech developers seem hell bent on getting to actual use, often dubbed “first-in-human” (FIH), as soon as possible.

So, what motivates the race to FIH? Why is it so important and meaningful to quickly achieve that first actual use case of a new medical device? Furthermore, are the motivations guided in a way that aligns with safety and efficacy?

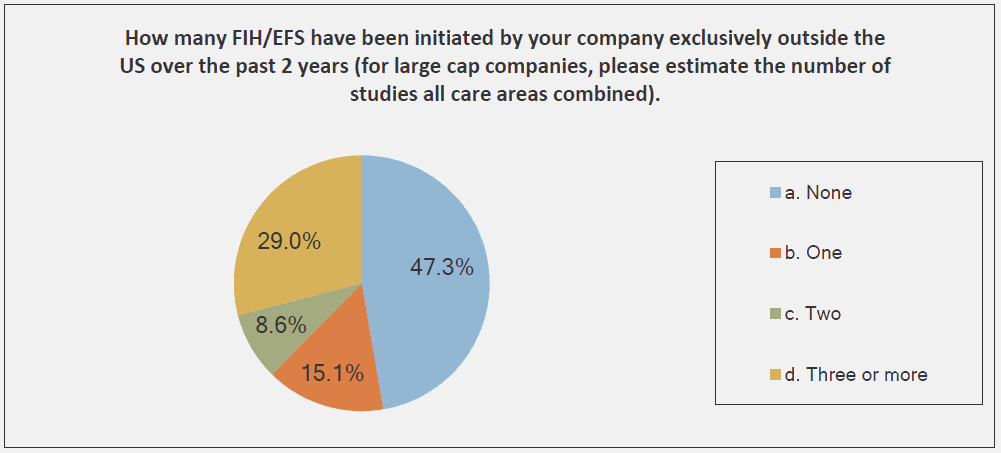

One of the biggest factors driving FIH interest is financial motivation. Specifically, medtech investors are increasingly looking to FIH as a significant milestone for funding purposes. And, medical device companies have responded to this phenomenon — so much so that many such companies seek opportunities to complete that FIH study outside the U.S.

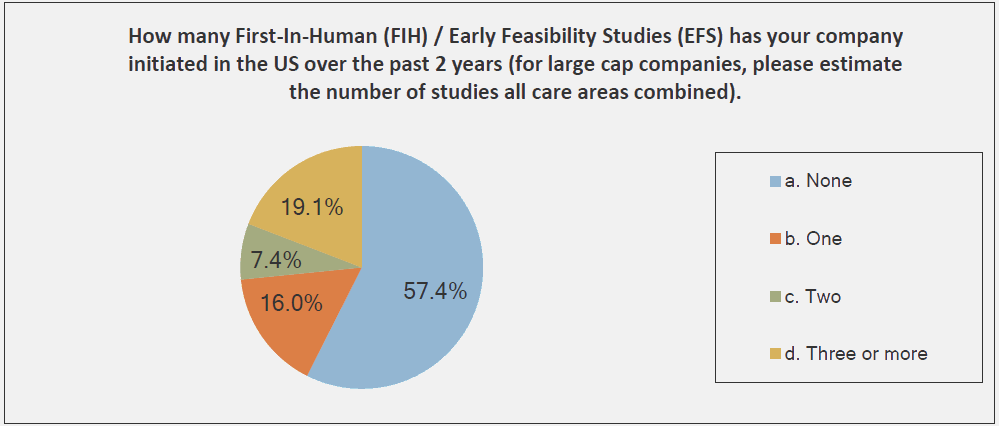

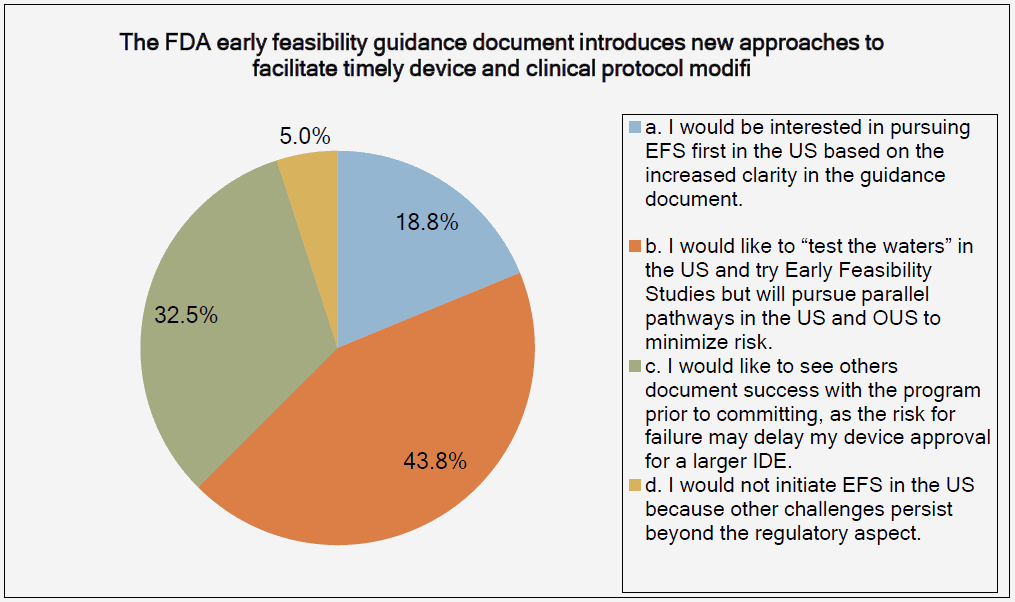

The graphs below, provided by the Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC) Clinical Trial Innovation and Reform Project Report, provide evidence to support this trend:

The reason that FIH has become an emphasis for investors is simple: A successful FIH study demonstrates that a medtech product performs under actual use conditions — a positive indicator of potential product success in the marketplace. With that promise of success comes return on investment (ROI) and reduced business risks.

Still, while all investors want to make money, it’s prudent to ask: Should first-in-human be a motivating milestone that triggers additional investment funding?

Travel back in time to the medtech industry of about ten years ago, and investor emphasis was different. At that time, the significant funding milestone was a regulatory submission, often in the form of a 510(k) submission.

Driving towards a regulatory submission and getting clearance also is a means of reducing business risks. Getting the go-ahead from FDA or another regulatory agency is substantial: It’s a nod that a device has been demonstrated as safe, and that a company can launch its product into market.

But, in today’s industry, preparing a regulatory submission is a late-stage product development activity. Achieving a regulatory submission means that design controls and product risk management have been documented and addressed, and that the device has been proven safe and effective to meet its specified indications for use.

All of this is very significant, of course. Yet, many times, a regulatory body may clear a device with little or no actual use. In such scenarios, are medtech companies faced with a business risk obstacle that can be obviated via a FIH study? More to the point, does a medtech company still have a significant business risk to overcome before there is substantial evidence to demonstrate the product’s effectiveness?

Perhaps.

Over the past couple of years, I have talked with hundreds of medical device companies, several of which are pursuing FIH studies all over the world. In many of these cases, I question whether or not these companies have adequately demonstrated that their devices are, in fact, ready for actual clinical use. Many seem to view FIH as the finish line of a race, of sorts.

There is a rush to construct a few prototypes, to conduct some preliminary bench testing and, in some cases, animal testing may be conducted. Then, a company might identify some part of the world where the regulatory environment is a little more lax when it comes to human use. Sound design controls and risk management documentation may or may not be in place, viewed as secondary and somewhat optional. But should they be?

To answer that question, consider FIH from a different perspective. Specifically, if a medical device company is pursuing FIH, then what should be done prior to initiating its study?

Well, FIH is about demonstrating that a medical device meets user needs and indications for use — a form of design validation. Design validation is about demonstrating that the medical device is the correct product for its intended purpose. And, since FIH is part of design validation, the products included in the study are to be production units.

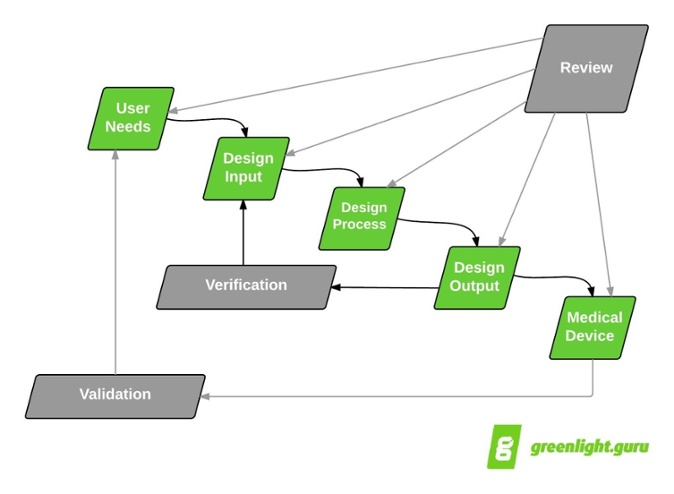

Working backward from design validation, additional design control activities must be captured and documented, as well.

That’s right: design planning, user needs, design inputs, design outputs, design verification, design reviews, and design transfer all should be addressed, documented, and contained in a design history file (DHF). Since FIH represents actual human use, it also is imperative that product risk management be documented. The risk management should assess the hazards, and then estimate the probability of occurrence and severity of harms.

Basically, going for FIH is analogous to building the first production units and using them clinically. Does this mean that the product used for FIH studies is the anticipated go-to-market, production version? Not necessarily. The FIH product often has a very specific purpose to demonstrate that the device works. It then is likely that, from this FIH platform, medtech companies will enhance product attributes and design features, and use the FIH findings to support additional regulatory submissions.

Thus, just because no strict regulatory requirements address geographic location when conducting FIH studies, do not view the opportunity as a free ticket to skip design controls and risk management. As medtech professionals, we all have an obligation to ensure that products used on people are as safe and effective as possible.

About The Author

Jon D. Speer is the founder and VP of QA/RA at greenlight.guru, a software company that produces quality, compliance, and risk management software exclusively for medical device companies. He is also the founder of Creo Quality, a consultancy that specializes in assisting startup medical device companies with product development, quality systems, regulatory compliance, and project management. Jon started his career in the medical device industry over 16 years ago as a product development engineer after receiving his BS in chemical engineering from Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology.