Flipping The Org Chart: Rethinking Where A Company's Focus Should Be

By Joanna Gallant, owner/president, Joanna Gallant Training Associates, LLC

In writing my last article about whether the life sciences industry has driven out people’s ability and motivation to think (see part 1 and part 2), I was reflecting on one of the most insightful comments I ever received. I had given a good manufacturing practice (GMP) refresher session in a company whose mantra was efficiency and speed. This led to a variety of process and cultural issues, because the desire for speed led to broken systems loaded with Band-Aids, corners being cut, people making mistakes, and more — which in turn created a poor quality culture within the company and led to deviations, scrap, and other problems. After the session, a manufacturing operator talked to me about employees’ frustration with the situation, saying, "Why don't people understand that if we focus on doing things right, efficiency will come?"

Truer words have never been spoken — and by a manufacturing operator, no less. This makes me think that our focus as an industry may be completely off.

The Reality Of Our GMP World — In Simple Terms

We run our companies with the intention of selling product to customers for profit, providing the money we need to run the business. So we set sales targets, then ask our sales and marketing departments to plan marketing campaigns and ensure we meet those targets. We also worry about expiring patents and look for a new product to fill that income gap. So we push R&D to develop new products, providing funding for the latest tools and strong personnel. We then tell our stakeholders about how well the company is doing, its future direction, and the return on their investments — in which we also review the performance of the existing products made by our Operations groups, and what they’re bringing in for revenue.

That revenue is the difference between the income from products sold and the cost of producing those products. Kept to the simplest terms (ignoring overhead, writeoffs and depreciation), the cost of producing a product is the sum of the costs of the materials required to make the product (components, containers, closures, packaging, and labeling), the costs of consumables used in processing (like laboratory reagents, cleaning chemicals, equipment lubricants/coolants, etc.), and salaries associated with the personnel doing the work in the various departments to support the production, testing, review/release, and shipping the product.

Companies want to maximize revenue by creating the lowest production cost possible, so we regularly look for ways to cut costs. This often means cutting staff or not filling open positions, putting off upgrades to equipment, implementing “Lean” and “OpEx” processes, or other cost-cutting activities. (To be fair, Lean and Operational Excellence are valuable activities, when used to improve processes and reduce waste, versus being used to justify cost-cutting measures.) And we look to implement “efficiencies,” which often means shuffling one part of a process from one department to another. These activities put stress on the operations people, who now have extra work from those positions that were eliminated or not filled and must deal with issues with the existing equipment (it hasn’t yet run to failure and won’t be replaced until it does). On top of that, we need people to work on the “efficiency” initiatives and other priorities, in addition to their daily list of job tasks. Then we’re surprised when deviations or issues occur, and those that cause us to scrap batches are particularly negative. These we typically call “operator errors,” mostly because they happened when a person was doing something. We address these by starting a human performance improvement initiative so that those same mistakes don’t happen again.

The way we currently do business makes it harder for the people generating our revenue to do so. At the same time, we’re increasing the cost of producing a quality product. It’s almost counterintuitive.

(I realize other areas of the business also face these problems, especially cost-cutting and staffing, but the following discussion focuses on Operations as a concrete example.)

The Phase Shift We Need To Make: Flipping The Org Chart

Since our ability to meet demand — and obtain the revenue that funds the business — comes directly from Operations’ ability to produce quality product at the lowest cost, would it not make sense to “flip the org chart” so that our focus is on ensuring the people making that product can do so? To me, this is the essence of the manufacturing operator’s comment.

Shouldn’t we make that area and those processes as good and reliable as possible? For the good of the whole business, I think yes.

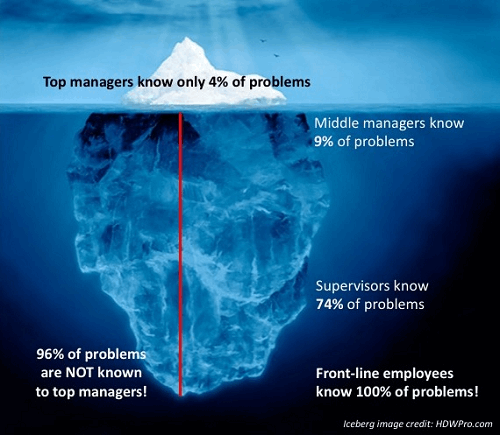

Figure 1: “Iceberg of Ignorance” study conclusions, illustrated visually

And no one knows how to do that better than the people who execute those processes every day. They know what works and what doesn’t, what processes are broken, and where the pain points are. Management-level personnel are typically removed from day-to-day operations (and in some cases, have never performed the work they’re leading), which means they may not have the data they need to make the best decisions for the company. But the cleaning staff, operators, facilities personnel, and analysts? They know all the holes, issues, or problems in any operation.

This was demonstrated in Sidney Yoshida’s 1991 “Iceberg of Ignorance” study, where he shows that 100 percent of problems are known to frontline employees, while only 4 percent are known to top management (see Figure 1).

What if we asked these folks what they need to do their jobs right, or what would make their jobs easier — because they will know, and they will tell us. But we must ask with the intention of listening and then figuring out how to give them those things, building our quality goals and objectives and resourcing plans around those needs.

If we did this, we could find ways to fix the broken processes and problematic equipment that keep creating deviations and failures. This means we could have possibly avoided the aging facilities mess and associated drug shortages that plagued the industry.

Fixing those issues reduces the amount of personnel time needed to document, process, and investigate deviations and nonconformances. It also eliminates many of the problems that are mistakenly termed “operator errors” and force retraining, again lessening the amount of personnel time spent producing a batch. These both lead to reductions in production costs — less personnel time required means lower salary amounts invested in each batch. At the same time, it reduces the time spent producing the product, because it’s done right the first time. (This also improves personnel stress levels by reducing time pressures and eliminating things that can lead to “blame culture.”)

Subsequently, we see improvement in the number of batches discarded due to those issues and investigational findings. This means we’re using purchased materials as intended, with less material going to scrap, so we further reduce production costs by having less waste with costs that need to be recouped elsewhere.

Overall, we’ve significantly lowered the cost of producing a quality product.

Since processes now work as expected, the number of successful batches increases, which provides more saleable product at a lesser cost to the business. This benefits the company in the form of a better, steadier revenue stream, because we can supply the predicted product demand (meaning fewer drug shortages industry-wide). It may also mean the company can find space in production schedules for new or additional products, increasing our revenue. We may even be able to sell the product for lower cost — which creates at least a competitive advantage, if not stepping toward addressing the industry-wide issue of drug pricing.

Let Joanna Gallant show you how to build a “Quality by Design” approach to eliminate human errors and risks in your manufacturing organization.

Organizational Strategies for Reducing Human Error in GMP Environments

Is This New Thinking? No.

Regulatory agencies saw this well before industry did and have been trying to lead us in that direction by:

- Encouraging the use of quality by design (QbD), to increase the likelihood that the processes we develop work appropriately in operations settings and ensure we have the information required to be successful. (See ICH Q8 (2009) and ICH Q11 (2012).)

- Driving toward quality risk management, to ensure that companies identify, understand, and address (or at least identify and plan for) those things that could have process and product impact and could lead to supply disruptions. (See ICH Q9 (2005).)

- Encouraging the use of PAT (process analytical technologies) to monitor and test batches during production to identify issues/problems before they become unrecoverable. (See the FDA’s 2004 guidance to industry.) This automation can also save personnel time and effort for tasks that must be performed by a person.

- Describing a process validation approach that encompasses continued process verification to ensure the process continues to work consistently, enabling early identification of equipment issues or process shift that may affect product quality. (See the FDA’s 2011 guidance to industry.)

- Expecting supply chain controls that ensure components work as expected and can provide the result we’ve defined as acceptable. (See the FDA’s 2016 guidance to industry.)

- Expecting quality management system implementations that encompass management reviews of product quality and process performance. These ensure senior leadership receives data that identifies operations processes that need attention and investment to ensure continued production of good quality product. (See ICH Q10 (2008).)

- Asking for sharing of consistent quality metrics, so that regulators can monitor how well we’re identifying and addressing problems internally. (See FDA’s draft 2016 guidance to industry.)

Industry, however, has been slow in adopting these approaches, for a number of reasons. Most of us don’t want to be the first to do something new, because of the uncertainty. We have no reference points, no examples to follow, and nothing to benchmark against, so we don’t know if we’ve done things correctly, and we don’t want to open ourselves up to regulatory inspection observations.

Resources, especially cost and time, also impact our willingness to try new approaches. For example, retrofitting a legacy manufacturing line with PAT requires process reworks, new equipment, validation, procedural updates, training, and possibly regulatory notifications or resubmissions that require approvals — the costs of which may not be worthwhile for legacy products. Alternatively, deciding to embrace the QbD approach to product development requires more time (or additional resources leading to more cost) to develop a new product, when we want new products available and generating revenue as quickly as possible.

Further, people also tend to view implementing automation as a means to reduce headcount — so when introduced, people often fear for their jobs and may stall the processes to the point where the projects are cancelled. In reality, we will always need people in these processes, but it may not be where they are or doing what they’re doing right now.

But inherent in this process is a better quality culture, more engaged employees, operational efficiency, and ultimately better business as a whole. So why wouldn’t we at least try it?

The Bottom Line

I ask you to think about this “flipped org chart” approach. From the senior leadership standpoint, there are a lot of positives here:

- The true internal threats to the business are known — and senior leadership can plan to address them before they have negative business impact, both internally and externally.

- Personnel see that their experience and ideas are valued by leadership, which leads to more engaged workers, better performance, and less turnover in the organization.

- Supply of product becomes consistent, at lesser cost — because the supply chain is as strong as it can be, and the process runs as expected as often as possible while experiencing minimal problems, driving better revenue, and benefitting the business as a whole.

- Regulatory agencies see that the business values doing things right and producing quality products, which could lead to fewer inspection observations and shorter inspections — meaning less business disruptions due to inspections, responses, and remediations.

Is this a threat to management, intended to weaken their position? No, not if done correctly. Senior leadership still drives the direction of the business and set expectations, even in a flipped organization, but the flip makes it easier for people to meet those expectations. And we as managers are ultimately responsible for enabling our personnel to meet organizational goals — doing so is what makes us successful as management.

But the leading goal of any business in the GxP space must always be getting good quality products to the patients who need them. Otherwise, why are we here?

Which brings us all the way back to our manufacturing operator: “Focus on doing things right, and the efficiency will come.”

About The Author:

Joanna Gallant is an experienced, solutions-driven quality and training professional who has spent more than 23 years in pharmaceutical, biotechnology, tissue culture, and medical device development and manufacturing environments. Over her career, she has provided regulatory, technical, skill, and management development training support to all operations functions, as well as IT, R&D, customer service, and senior management. Now, as a training system consultant, she works with clients to design and deliver custom training and build/remediate training systems, including in support of regulatory audit observations and commitments.

Joanna Gallant is an experienced, solutions-driven quality and training professional who has spent more than 23 years in pharmaceutical, biotechnology, tissue culture, and medical device development and manufacturing environments. Over her career, she has provided regulatory, technical, skill, and management development training support to all operations functions, as well as IT, R&D, customer service, and senior management. Now, as a training system consultant, she works with clients to design and deliver custom training and build/remediate training systems, including in support of regulatory audit observations and commitments.

Joanna has been a GMP TEA member since 2001, and now serves on the Board of Directors as an advisor. She is one of the founders of the Biomanufacturing Certificate Program at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and became an Adjunct Professor at the Boston University School of Medicine's Biotechnology degree program in 2011.

You can contact Joanna at Joanna@JGTA.net or connect with her on LinkedIn.