Framework Methodologies For Medical Device Usability Engineering

By Sean Hägen, founder & director of research and synthesis, BlackHägen Design

How a medical product is perceived enables usability and has scientific premises in human factors/usability engineering (UE) and industrial design. Each discipline shares theories that, when harmonized, can become a method to optimize usability, which is ease of use and use safety. The importance and challenges in the relationship between medical device design, UE, and the aesthetic development process significantly impact usability and delight. There are two theories that complement each other to create an applicable methodology: affordance and product semantics.

UE research has documented the nature of a user’s choices and user interface behavior, as they are influenced by aesthetics, specifically, initial visceral impressions and intuitiveness of use. So, it is much more than a marketing objective. Consider that the apparent usability of a device may be just as important as the actual usability. The user’s initial impression of a device and their expectation of how it will function and meet their needs are often critical to safety and efficacy in the healthcare context of use. The user’s initial impressions can not only be characterized and planned for, but actually purposely designed into the user experience, enabling the desired affordances. That is, a user’s perceptions of potential interaction and outcome with an object, based on its properties, are referred to as its affordances.

Addressing the affordance theory means understanding what a user will likely perceive and expect of a proposed design interaction. The device designer should encourage affordances that benefit the user and discourage interactions that may be unintended and thus could potentially cause use error. This may also mean limiting certain affordances in a device design. In this capacity it is a subset of product semantics, a design methodology for enabling the desired affordances. The industrial design theory of product semantics informs the design process and enables a self-evident user interface through the qualities of the device’s aesthetic, form, texture, color, and metaphor. The aesthetic composition, or semantic, of a design does not literally explain what it does; rather, it influences how the user interprets it. When the two theories are integrated, product semantics can be a framework methodology to proactively enable the desired affordances in the design of a device.

For example, in the case of designing a laparoscopic instrument, the user interface features and grip need to be considered for both aesthetics and functionality in order to intuitively meet the user’s expectations. Instrument A (Figure 1) has three grip opportunities that afford the user flexibility in both learning and practice. Form, texture, and color provide visceral cues as to where and how to grip the instrument. With instrument B (Figure 1) form, color, and texture were also used to indicate grip and interaction; however, two issues influence the intended use of the device. First is how the semantics afford proper grip and are impacted by negative transfer bias due to being unfamiliar when applied to a laparoscopic instrument (as opposed to a kitchen tool or gaming control). Second, there is a rotatory control knob that was not easily identifiable during usability testing due to its colocation with the cable strain relief, despite texture indicating it is a user interface. Instrument C utilizes the metaphor of scissors to afford proper interaction and a mental model affording what the distal end of the instrument is doing.

Figure 1: Form and function in laparoscopic instrument design

Another example of utilizing metaphor in a design can be demonstrated in the development of a new autoinjector where the existing form factor is that of an ink pen. In this case, due to a new microfluidic technology, the design is significantly more compact than the predicate and the pen metaphor does not work. In addition, the act of injecting could no longer be a stabbing motion. The form and activation of a common desktop stapler were used in the design for the autoinjector semantics to afford a new user with a familiar usage model (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Design semantic utilizing metaphor

As the design evolved, both technologically and from user evaluations, the design semantics also evolved to enable intuitive interaction with the device and its packaging features (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Development and implementation of product semantics

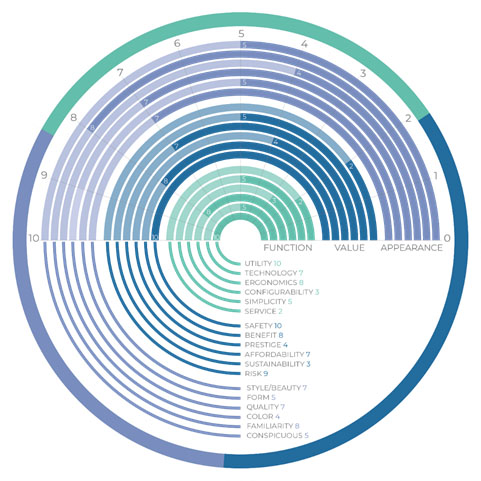

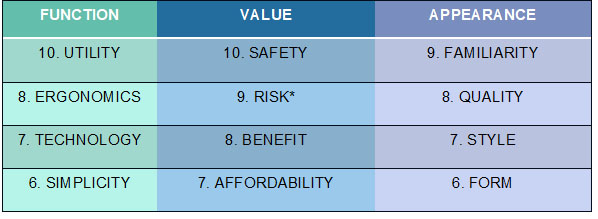

It may be apparent that incorporating multiple semantic attributes works well in concert, complementing and reinforcing the intended affordance. The approach to developing the design semantics can often be obvious to the designer, especially with an iteration of an existing design; however, requirements are often more complex for medical devices, especially a novel one. A process for aligning requirements and the stakeholders that influence them is a useful approach. The application of a perceived attributes methodology, where attributes of function and aesthetics define a user’s perception of value. The user’s assessment of a device can be based on their perceived value as a result of function and appearance – these are interconnected and influence each other. This method can connect the two theories of product semantics and affordances into a cohesive approach to enable a meaningful and appropriate aesthetic by providing a common vernacular across development disciplines.

A typical challenge that usability engineering specialists have for defining user needs and translating user interface (UI) requirements is trying to understand and characterize intuitive use, or worse yet, "ease of use." Having common definitions of function, aesthetic, and, ultimately, value can help characterize such ambiguous requirements with a documented baseline. Once these attributes are established, they become a means for articulating the design semantics that enable the desired affordances.

Returning to the example of developing a laparoscopic instrument, a matrix mapping function, aesthetic, and value (see Figure 4) can provide a means to establish priorities in the development of design semantics (see Figure 5). This approach can align a cross-functional team in the development of semantic design schemes and the interpretation of requirements.

Figure 4: Perceived attributes (adapted from The Relationship of Function and Appearance to Value, Privitera & Johnson 2009)

Figure 5: Prioritized perceived attributes for laparoscopic instrument

This approach for communicating attributes and the infographic (Figure 4) is an example of a process tool; it is not a prescription. It can represent user rating of importance and/or ranking of priority. The purpose of such an exercise is to provide objectives for the design semantic approach.

It should be noted that the development of the UI requirements may often occur after the industrial design, if the initial ID is conducted pre-design controls.

Use-safety impacts the design from the perspective of regulatory objectives Ease of use impacts design from the perspective of marketing business objectives and often is led by usability engineering and industrial design. However, the engineering stakeholders for regulatory objectives are not necessarily the same as those focused on technology or usability. Use-safety is the responsibility of UE, which may be initiated as part of system engineering or implemented as part of quality engineering. Proactively addressing these discrete objectives by developing design features that are perceived in a manner that is intended to initiate intended behavior as a significant impact on implementing the more challenging requirements like ease of use.

Often the implementation of these varied agendas is translated into user interfaces by industrial design. The UI design is responsible for influencing the user to behave and use the device as intended by both the device manufacturer and the user. The connection of these disciplines and objectives is typically documented in requirements. This is where the deployment of a product semantics methodology, enabling intended affordances through a collaboration tool such as perceived attributes, can align all the designers’ interpretations of the requirements.

Consider the UE process and the validation of the UI design. Formative studies typically identify tasks that have usability issues, informing use-related risks, and many of those are characterized as not intuitive, requiring the design to be more resilient and user friendly. Those evaluations are purposely designed so that the user does not know how the device is intended to operate in order to expose usability issues and, by default, demonstrate intuitiveness. When UE reports on formative user evaluations, there is language used to describe the deficiencies. These can further inform the development of the perceived attributes that, in turn, inform the product semantics.

Conclusion

When a device and user interface are being developed, the decisions and anticipation of intended interactions are influenced by aesthetics and are most crucial in the design process. Usability engineering can define what affordances the design will provide the user to meet the desired expectations, and industrial designers can utilize a product semantics method to embody those affordances. Consider product semantics as a means to develop design language for optimizing usability, aesthetic, shape, form, color, and metaphor, which speaks to the end user and influences their interpretation. The syntax is the affordances and the vocabulary is its perceived attributes informed from the UE process.

About The Author:

Sean Hägen is founding principal and director of research & synthesis at BlackHägen Design. He has led design research and usability design, within both institutional and home environments, across 20 countries. His role focuses on the user research and synthesis phases of product development, including usability engineering, user-centric innovation techniques, and establishing user requirements. Hägen has a bachelor's degree in industrial design with a minor in human factors engineering from the Ohio State University. He is a member of IDSA (the Industrial Designs Society of America) and HFES (Human Factors and Ergonomics Society), having served two terms on the former’s Board of Directors.

Sean Hägen is founding principal and director of research & synthesis at BlackHägen Design. He has led design research and usability design, within both institutional and home environments, across 20 countries. His role focuses on the user research and synthesis phases of product development, including usability engineering, user-centric innovation techniques, and establishing user requirements. Hägen has a bachelor's degree in industrial design with a minor in human factors engineering from the Ohio State University. He is a member of IDSA (the Industrial Designs Society of America) and HFES (Human Factors and Ergonomics Society), having served two terms on the former’s Board of Directors.