How To Know You've Passed Validation Testing (And What To Do If You Haven't)

By Peter Sneeringer, Design Science

When studies are successful, human factors (HF) validation can be as straightforward as checking off the boxes on a study protocol. If all the pieces of testing don’t come together as planned, however, HF validation can be a complicated endeavor. At the recent HFES Symposium on Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care, we shared our thoughts on how to know whether or not you’ve cleared that last hurdle.

As consultants who often help biomedical companies that struggle with applying human factors to their products, we’ve been privy to lots of complicated situations over the years. Through our experience, we’ve identified several key questions that can help to determine whether or not a summative submission is likely to be accepted or rejected by the FDA. In cases where it is likely that a submission will be rejected, we’ve also identified some strategies for how to move forward. (It is important to note that our experiences are not necessarily representative of all interactions with the FDA.)

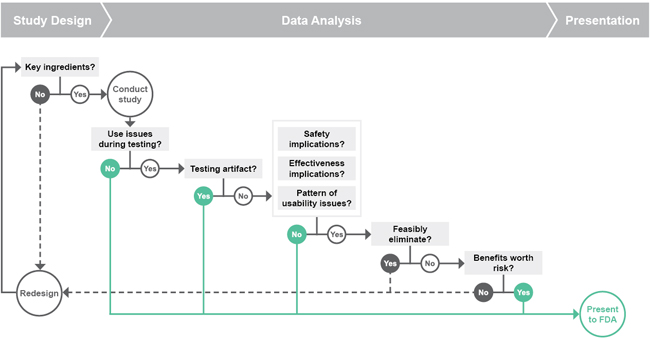

We use the series of questions shown in the flowchart above as a guide for anticipating the FDA’s feedback on our HF validation studies. It may seem complicated, but it’s really just a matter of considering whether or not we have:

- Designed the study properly,

- Analyzed the data and obtained defensible results, and

- Presented those results well.

If you didn’t have perfect results in your validation testing, ask yourself the following six questions to see if you may still be able to move forward (or if you need to start over).

1. Key Ingredients

Following the flowchart step-by-step, the first question we ask is: “Have we designed the right validation study?” That is, “Does the study have all of the key ingredients for a summative?”

According to the 2011 FDA Draft Guidance Applying Human Factors and Usability Engineering to Optimize Medical Device Design, a summative needs to:

- Test critical and essential tasks

- Test a representative product

- Recruit representative users

- Simulate the representative environment

- Provide representative training

- Record sufficient and appropriate data

It’s fairly straightforward to predict failure if your summative study does not include one of these key ingredients.

2. Use Issues During Testing

The next question is often the easiest to answer: “Were there use issues that were observed during testing?” There almost always are some use errors or difficulties that occur during testing, in which case we need to explore the root causes and consequences of those use issues.

3. Testing Artifact

To explore the root causes of issues encountered during testing, we ask: “Are we likely to see these use problems in real use, or did they only occur due to the simulated nature of the testing?”

Although we design simulated-use usability testing to closely mimic real-world environments, the simulated environment will never be entirely perfect. If the use problem was, in fact, a testing artifact that would not occur in real use, then the use problem is likely to be defensible and the results are likely to be accepted by the FDA. We just need to be sure to provide rationale explaining why a use problem is a testing artifact in the human factors engineering (HFE) / usability engineering (UE) report. (For instance, if you must wait 30 minutes after removing a device from refrigeration, you will not expect the user to actually wait 30 minutes during the testing session). Note that we can really only make a strong case for testing artifact by including subjective feedback from the participant about the use error, which emphasizes the importance of obtaining participant feedback during a validation study.

If the use problem is not a testing artifact, we then need to investigate the real-life consequences of such an issue.

4. Significant Use Error Consequences

To identify the real-life consequences of any observed use errors, we need to look at three factors: safety implications, effectiveness implications, and patterns of usability issues.

First, we must ask: “Does the error have potential safety implications?” Typically, according to a product’s risk assessment, a use error with safety implications would be one in which the consequence requires medical intervention. For example, an error that forces a nurse to take action to help a patient has safety implications, while a drop of blood resulting from an injection does not.

The next consequence to consider is whether or not the error has effectiveness implications. In other words, “does the error reduce or eliminate the intended medical effects of the product?” If a user can’t remove the cap on an auto-injector, it’s not going to be very effective; but if a user takes slightly longer than expected to navigate a screen sequence, the product ultimately still has the intended result. Note that in the newly released version of IEC 62366-1, the definition of safety folds in this concept of device effectiveness.

The last question to consider is: “Do the errors show any patterns of usability issues that suggest that users are likely to struggle with the product?” Due to the small sample sizes in human factors testing, the FDA looks for patterns of usability issues that point to deficiencies in product design, which, given a larger sample size, might result in significant use errors.

If we ask these three use error questions and are able to say that the error does not have those consequences, we feel confident with submitting the product to FDA. However, if the use problems do have significant consequences, then things can get pretty tricky.

5. Feasibly Eliminate the Error

The next question is: “What can be done about the use problem?” or “Can we feasibly eliminate the error?”

This is one of the most important — and most challenging — questions to answer, because there’s a gray area when considering which mitigations are “feasible.” Is implementing a comprehensive training program feasible? Is reconsidering the entire design of the device feasible? In our experience, FDA’s expectations for feasible mitigations are higher for more sophisticated products with higher risks, like infusion pumps and dialysis machines. Potential mitigations can only be considered feasible if the function of the device is not compromised.

Obviously, when considering feasible mitigations, cost always comes into play. How much will a product redesign cost? How does that factor into the feasibility argument? From a regulatory perspective, cost is not a barrier to feasibility unless the cost of the mitigation is so burdensome that it would make the product financially out of reach for its users, thereby negating the product’s benefits. However, cost can certainly influence decisions about what mitigations will solve the problems experienced in testing.

The bottom line here is this: If you can think of a feasible mitigation, the FDA probably can as well. So it’s important to ask yourself, “What WILL we do to fix this?” rather than “Will the FDA accept this, as-is?”

6. Benefits Outweigh Risks

In cases where we find that use problems with safety implications cannot be feasibly eliminated, the question to ask is: “Do the benefits that this device offers the patient outweigh the inherent risks associated with using it?”

As a product manufacturer, of course you’ll want to believe that the benefits are substantial enough to justify some small amount of risk. However, this is a line of thinking that most manufacturers should avoid, because not only is it a difficult case to make, but it will also likely require a lot of communication with FDA to ensure that they understand the benefits of the product. We consider the benefit-vs.-risk argument a last resort, only to be used for treatment areas that currently lack any viable treatment options — meaning that the benefits are sure to be substantial for the patient population.

Presentation of Results

Now, if we’ve asked all these questions about the protocol and the data, and we think it will be smooth sailing through FDA, the final issue is to properly present the results. The report needs to be clear and to the point, while still providing the agency with all of the information they need. Specifically, when describing each use issue observed during testing, we need to include:

- Objective and subjective data

- Root causes

- Consequences

- Mitigations

- Residual risk

Including all of the information listed above helps us build a persuasive case to the FDA by showing the agency that we not only understand how users are using the product and what risks are associated with its use, but also that we have done everything possible to mitigate those risks.

What To Do If You Haven’t Passed

If, on the other hand, we go through that flowchart and find that the product is not in optimal shape, what’s next? The key here is to be proactive. Acknowledge that there are shortcomings with the device and seek ways to address them. Remember to think, “What WILL we do to fix these issues?” rather than “Will the FDA accept this, as-is?”

Plan a follow-up study and seek feedback on the study design from the agency. Tell the agency how you plan to address the issues, and ensure that they agree with that plan before proceeding. Often, you can focus the additional studies on the changes made to the product rather than revalidating the entire system. Depending on the results, you may also be able to conduct the follow-up testing with a subset of users.

A question we often come across is whether or not to submit the study results even if they don’t look promising. We wouldn’t necessarily endorse that, but if you decide to submit your results as-is, ensure that you are upfront about the limitations of the product and your strategy to implement additional mitigations, as necessary.

This article is an adaptation of a presentation given at the HFES Symposium on Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care.

About The Author

Peter Sneeringer holds a B.S. in mechanical engineering and an M.S. in human factors engineering from Tufts University. At Design Science, he directs and conducts human factors projects involving usability testing, heuristic analysis, and the design of instructional materials. He has experience with a wide variety of medical devices, particularly drug-delivery devices, diabetes-related products, and home healthcare devices.