Human Organ-Mimicking Chip Could Revolutionize Clinical Trials

Harvard researchers have landed the London Design Museum’s 2015 Design of the Year award for their “Organs-on-Chips,” a series of devices that use stem cells to mimic organs of the body. Many experts believe this technology could lead to a paradigm shift in the world of clinical trials and individualized medicine, and could replace animal testing.

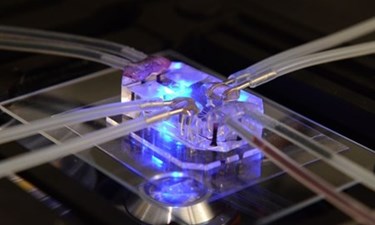

The Organs-on-Chips technology, created at Harvard University’s Wyss Institute, is a piece of clear flexible polymer, roughly the size of a flash drive, that contains hollow microfluidic channels lined with human stem cells coaxed into mimicking a particular organ. So far, the research team has designed chips to mimic fifteen organs including the heart, lungs, liver, eyes, and intestines.

Because the chips use human cells, researchers say they can predict human response with a precision that outstrips traditional testing methods, which usually involve animal models. While an animal’s reaction to a drug or cosmetic can provide some insight into how a human body will respond, the science isn’t 100 percent reliable, and an inaccurate preclinical prediction can cost developers millions of dollars and years of setbacks.

According to researchers’ comments on the Wyss Institute website, “Clinical studies take years to complete and testing a single compound can cost more than $2 million. Meanwhile, innumerable animal lives are lost, and the process often fails to predict human responses because traditional animal models do not accurately mimic human physiology.”

Anthony Holmes, from the National Center for the Replacement, Refinement and Reduction of Animals in Research, called the Organ-on-Chips technology “revolutionary,” and told The Independent that potential applications could lead to a better understanding of human and animal health, personalized drugs for individual patients, and safer drugs that are available more quickly.

“The Organs-on-Chips allow us to see biological mechanisms and behaviors that no one knew existed before,” said Don Ingber, founding director of Wyss Insitute, in an article for The Guardian.

With this much potential, the tissue chips caught the attention of several U.S. government organizations. The National Institute of Health (NIH), the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have pooled their resources and launched the Tissue Chip For Drug Screening Initiative (TCDSI), intended to fund research that could create and refine this technology.

Last year, the NIH awarded $17 million to research institutes with tissue chips in development. NIH director Francis Collins told GenomeWeb, “The development of tissue chips is a marriage of biology and engineering, and has the potential to transform preclinical testing of candidate treatments, providing valuable tools for biomedical research.”

Though the technology is still in its infancy, the chips hold such revolutionary potential that they caught the attention of the London Design Museum’s award selection committee, who remarked in a press release that the award recognizes designs that could positively impact society both now and in the future.

Gemma Curtin, Designs of the Year 2015 exhibition curator, said “This winning design is a great example of how design is a collaborative practice embracing expertise and know-how across disciplines.”

A start-up named Emulate will commercialize Harvard’s technology, and currently is in talks with Johnson & Johnson to begin preclinical testing.