6 Indispensable Tools To Drive Effective User-Centered Design

By Craig Scherer and Carolyn Rose, Insight Product Development

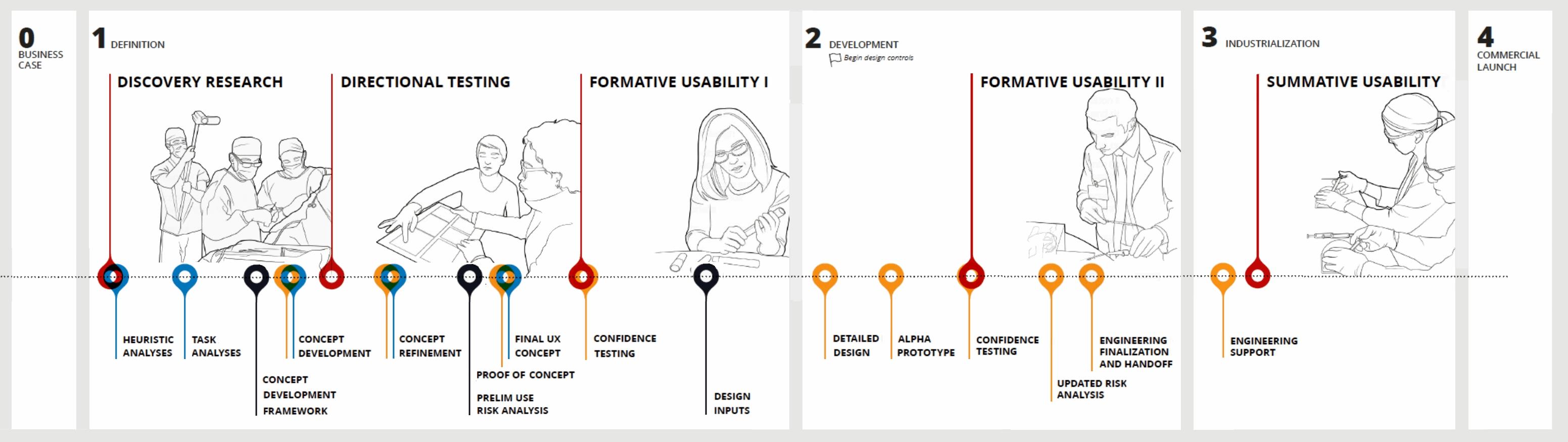

Effectively identifying, prioritizing, and translating user needs into design guidance is a key component of developing a successful medical device. The primary goal of this process is to develop a device that not only meets the FDA’s criteria for safety and effectiveness, but also one that provides the best possible user experience for all stakeholders.

The successful application of user-centered design principles relies on iterative and frequent feedback from stakeholders throughout the entire development process. This research also provides the design team information with which to identify, document, and better manage risk throughout the design cycle.

These activities can be further optimized by clearly understanding the goals, tools, and outputs that are expected at each stage of research. With every research touchpoint, it’s important to start by concisely defining the purpose of the effort (what do we need to learn?) and, from there, determining the tools most likely to fulfill the need.

Prototyping To Learn

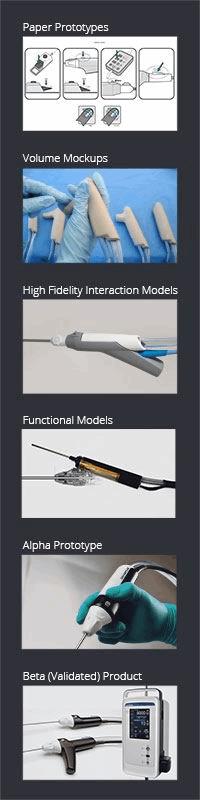

In terms of tools, prototypes are an extremely effective way to communicate ideas to people. It is said that, if a picture is worth a thousand words, then a prototype is worth a thousand pictures. Prototypes can vary widely in their fidelity and purpose but, at their core, they provide a shared language – between designers and users, and across disciplines on a development team. They also can provide buy-in and clarity for decision-making during development.

Prototypes can scale in fidelity based on the stage of development and what kind of questions need to be answered. Scaling fidelity mitigates unnecessary budget and time investment by development teams. For end users, it focuses attention on the specific attributes of an idea under development.

Here are six of the most effective prototypes that continue to inform our product development activities:

Here are six of the most effective prototypes that continue to inform our product development activities:

- Paper Prototypes can include everything from quick probes — which entail research participants responding to pictures or words as they relate to the research topic — to storyboarding, which, just like Hollywood, takes the subject on a journey through a story representing a process or work flow.

- Volume Mock-ups are aimed at understanding the impact of scale on an environment or interaction. Early scale models might be leveraged to determine things like portability or storage. Early rough mock-ups can be used to determine the extent to which a device could feasibly move within confined spaces or accessories for chronic disease management; they can answer questions like “is this something I can conceivably have with me at all times?"

- Appearance Models, like volume mock-ups, are non-functional solid representations of designs, but are of much higher fidelity. They are best used to convey issues like size, form, portability, grip styles, etc. They also can accurately depict user interactions and experiences, and can be used to obtain feedback on details like control and indicator locations. This level of fidelity often is used when a single overall design direction has been chosen.

- Functional Models are the direct counterpart to Appearance Models. They are functionally accurate, but can be very rough in appearance. These prototypes also are known as integrated proof-of-principle models or system breadboards, and can be used to test functionality and utility of the technology package. Still they do not directly represent the intended final user interaction. This level of prototype often is used for animal or cadaver studies.

- Alpha Prototypes are where form and function come together as one. These models are production-intent in terms of aesthetics, configuration, and functionality, but are produced from non-validated tools and processes. Typically created using a combination of prototyping methods, such as machining and 3D printing, these models represent the final device to be commercialized, and can be used to accurately evaluate usability, user interaction, functionality and safety.

- Beta Units are not actually prototypes, but are production products created from validated tools. These initial builds are used for usability validation, also called Summative Usability Testing.

Decisions, Decisions, Decisions

How we choose what type of prototype to use is a function of three important questions. These questions are interconnected and can be applied across a range of issues, from understanding an early idea or technology’s core value and applications, all the way through to understanding usability of a specific design embodiment.

We must ask, “What specifically do we want to learn at each stage of research?” Research collateral that helps us uncover attitudes and emotions, or help to envision an experience, may be very different from research designed to help us gauge a selected direction’s feasibility.

To develop the most effective user experience prototype, we also must understand, “Where are we in the process?” If it is early in the development process, we may be trying to understand the overall product environment and landscape, or we may want to better understand workflows and efficiency improvements. As development progresses, we will choose prototypes that assist the design team with selecting and refining early concepts, or we might want to better understand users’ tolerance to change.

As time progresses on the project, the number of concepts, divergent at first, begin to converge and narrow. As we move closer to completion of concept development efforts and move into detailed design, and ultimately industrialization, we develop higher fidelity prototypes that help us finalize and ultimately validate the usability of these chosen directions.

Finally, logistical issues can affect the decision when selecting a prototype style and fidelity, asking “Where and how do we need to engage with users?” Research may be conducted in the actual or intended environment of use. This may present challenges, for example, if the environment is an operating room or another crowded clinical space. Likewise, research can be effective over the web or remotely. Both of these scenarios may require paper prototypes to convey intent. Conversely, we may be evaluating usability in relation to functionality in a mock-surgical setting, in which case both Appearance and Functional Prototypes may best enable the research.

Wherever you are in the process, whatever questions you need to answer, there are a variety of user experience prototypes that you can call on to best inform your development process. Your research outputs inform both the user experience and technical teams, which in turn allows them to more effectively interact with each other and support the research efforts. This interaction of disciplines also effectively informs risk-mitigation strategies, which ultimately provides the most appropriate, safe, effective, and optimal user experience solutions for your medical device challenges.

For more information and a more comprehensive map of this process, visit Insight here.

About The Authors

Craig Scherer is senior partner and co-founder of Insight Product Development. Craig plays an active role in key account management, working with companies ranging from early stage tech organizations to the largest healthcare OEMs. He is also a director of Insight Accelerator Labs, Insight's in-house med device accelerator, helping medtech start-ups deliver transformative technologies to healthcare. Craig holds a BFA in industrial design from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and an MBA from the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Carolyn Rose is director of research and strategy at Insight Product Development. Carolyn works with Insight's clients generating meaningful research insights and defining actionable market opportunities. She manages a team of researchers in an immersive, process-oriented approach to better understand the behaviors, expectations, and motivations of end-users, as well as the environments, attitudes, and trends that shape them. Carolyn earned BAs in both industrial design and Spanish linguistics and literature from Syracuse University, and holds a master’s in design methods from IIT’s Institute of Design.