Medical Device Cybersecurity Alerts On The Rise

By Mike Kijewski, MedCrypt

In the past 18 months, the FDA and DHS have been warning the medical device industry about the danger of cybersecurity vulnerabilities in networked medical devices. But the number of medical device cybersecurity alerts has more than tripled in the last three months. Is this an anomaly or the new normal?

Medical devices can be hacked. This isn’t news to most. In August, the FDA issued its first ever cybersecurity-related recall of an implanted medical device, affecting about 450,000 patients. Additionally, the U.K.’s National Health Service (NHS) hospital system was hit by a ransomware attack in May 2017, affecting many healthcare IT systems and medical devices. This isn’t shocking. Experts have been warning of medical device cybersecurity dangers for a long time.

What is shocking, however, is the recent flood of alerts about different medical device vulnerabilities. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security has a team called The Industrial Control Systems Cyber Emergency Response Team (ICS-CERT). This organization provides a database of alerts and advisories related to cybersecurity issues in technology used in “Critical Infrastructure.” ICS-CERT has included cybersecurity alerts about medical devices for the past several years.

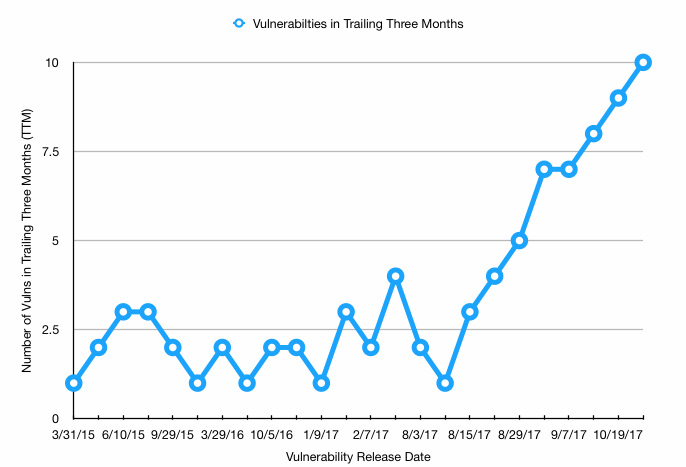

According to the ICS-CERT database, at any given time between January 2015 and July 2017, there were between one and four reports of medical device cybersecurity vulnerabilities issued in the prior three months. These issues ranged from difficult-to-exploit vulnerabilities in obscure hospital-based devices, to patient health information (PHI) being stored in plain text on glucose monitors used by diabetics.

But, starting in early August 2017, a new batch of advisories was issuing every two weeks. As of Oct. 27, 2017, there were 10 advisories issued in the last three months. Some of these are vulnerabilities that have been in the news for a while, and some are brand new issues found by security researchers.

This uptick in advisories begs three questions:

Why are there suddenly more alerts than in the past?

There are only two possible answers to this question. Either a small group of recently released medical devices had some issues that were found quickly, or researchers have just begun to focus on these issues, and the issues are widespread across all classes of medical devices.

Many of the devices for which alerts are issued have been in the field for several years, indicating that the problem is not limited to recently released devices, but plagues all medical devices. Three years ago, there were only a handful of security researchers looking into medical device security. With the increased focus on this issue, more and more researchers are turning their sites toward these devices. One can only assume the focus of “bad guys” has followed suit.

Will this trend continue, or is it an anomaly?

As researchers continue to dig into these devices, the frequency of vulnerability disclosures will only increase. In fact, the number of vulnerabilities found is not limited by the number of vulnerabilities that exist, but by the number of researchers looking into the problem. I would not be surprised if one out of four medical devices released in 2018 is found to have a security issue at some point in its useful life, meaning the number of advisories will increase considerably in the near future.

How will medical device vendors deal with these issues in the future?

Medical device vendors can choose to reactively or proactively address the problem. Manufacturers that choose only to react to security issues once they are found are likely to lose sales and spend significant engineering resources fixing vulnerabilities through recalls.

Some vendors will choose to take a proactive approach to the security of their devices, adding layers of security redundancy. This means that vulnerabilities in their devices are less likely to be found, and recalls stemming from vulnerabilities in related technologies (such as Windows vulnerabilities and WiFi issues) are less likely to require an urgent software patch.

Vendors who choose to address security proactively should determine which functions in their device would be most problematic if hacked. For example, an insulin pump that receives data over Bluetooth should have cryptographic signatures on the data it is receiving, so it can verify the data is not coming from a hacker. This and other security features can often be incorporated with a few lines of code from commercial security vendors.

Often, the biggest obstacle to including security features in devices is the rush to get products to market. When a product manager needs to decide between including a clinical feature or a security feature, the clinical feature almost always wins. Ways to address this include having a mandate that a fixed percentage of engineering resources go toward implementing security features, or designing in a security improvement development cycle before the device design is finalized.

Some devices, like implantable cardiac defibrillators, use such low power processors that certain security functions are not possible. Device vendors do need to weigh device functionality against security, and may find that certain devices can’t include proactive features. But, these devices then need compensating controls placed on their usage to ensure they are not vulnerable to hackers. As the small processors that these devices use become more powerful, vendors should look to include cryptography features when possible.

The most important factor affecting the future of medical device cybersecurity is how regulatory agencies prioritize this problem. As a fan of free markets, I usually prefer to see customers driving the features device makers include. But the U.S. healthcare system is not a traditional free market, and healthcare providers are not properly incented to demand security features in medical devices. This is a situation where the FDA and similar regulatory agencies need to ensure the safety of patients through guidelines and regulations related to cybersecurity.

The FDA’s recent guidelines on pre- and post-market cybersecurity are helpful in highlighting the importance of security to device vendors. Yet many vendors see these guidelines as optional, and are waiting for the FDA to require cybersecurity features in devices before investing significantly in this technology. The FDA has dispelled the notion that security is “optional,” but many device vendors still haven’t acted to address these issues in a meaningful way.

The rate of cybersecurity vulnerabilities found in medical devices is likely to increase steadily over the next 18 months. It is only a matter of time before the “bad guys” use these devices in a way that harms a patient. Our industry must move quickly to prevent these events from being as common as hospital PHI breaches.

About The Author

Mike Kijewski is the CEO of MedCrypt. Mike is passionate about new advances in the intersection of internet technology and healthcare. Prior to starting MedCrypt, he was the founder of Gamma Basics, a radiation oncology focused software startup. Gamma Basics was acquired by Varian Medical Systems in 2013. Mike holds an MBA from the Wharton School, and a Master of Medical Physics from the University of Pennsylvania