Medtech Needs A Clearer Regulatory Definition Of Clinical Decision Support Software

By Scott Thiel and Jim Williams, Navigant Consulting

The definition of a medical device in the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) is purposefully broad — some say too broad. It allows the FDA to reserve potential oversight of many healthcare products, including software. For example, some software development companies have bristled at the FDA’s potential to regulate their products.

A relatively new type of software making its way into the healthcare arena, clinical decision support (CDS) software, takes in patient information and then presents it to the user in a manner that supports decision-making regarding health, diagnosis, or therapy. Based on the general purpose of CDS software, it meets the definition of a medical device, and therefore could be regulated by the FDA.

CDS software has become something of a regulatory poster child for healthcare software. Many practitioners and companies are interested in using CDS software to improve healthcare delivery and, potentially, outcomes, but there is ongoing debate over how CDS software should be regulated by the FDA. Typically, FDA issues guidance documents to help industry and FDA employees understand current Agency thinking on how certain products are regulated. However, despite previous indications from the FDA that issuing a guidance document for CDS software was one of its high priorities, debate in Congress prior to passage of the 21st Century Cures Act delayed FDA’s issuance of the guidance. This informational void has left many companies without a clear understanding of the potential regulatory burdens associated with CDS, thus slowing the introduction such software into the market.

To date, FDA has assessed CDS-like applications on a case-by-case basis. This approach can introduce delays in getting an app to market, and may cause inconsistencies among FDA’s assessment of different apps. FDA has issued more general guidance documents covering medical device data systems (MDDS) and mobile medical apps, and these documents are great for what they cover, but they only a nod to CDS software, unfortunately, rather than a detailed discussion.

Click Image To Enlarge

FDA also is not in the habit of making specific device decisions without having had some experience with them; this includes software. As such, new concepts or applications in development need to be described in language comparable to that in the mobile medical app and MDDS guidance documents. Most of the time, companies wanting a definitive regulatory classification determination for a product get FDA’s input via a 513(g) filing or a pre-submission. However, these processes add time and cost that some companies — especially start-ups — cannot afford.

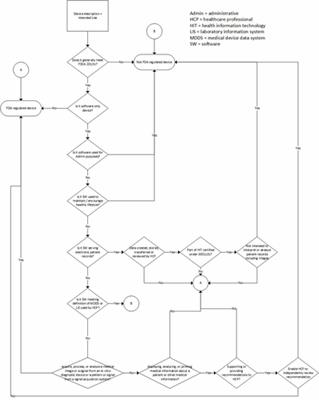

Congress attempted to address CDS software, in part due to pressure from constituents, in the 21st Century Cures Act (Cures) signed into law in December. Cures is a broad-reaching document that includes a section (§3060), carving out certain types of software from the definition of a medical device, thus removing potential FDA oversight. CDS software meeting certain criteria is included in this carve-out, but the decision flow used to arrive at the carve-out (Fig. 1) is convoluted and prone to different interpretation by different readers.

The introduction of Cures also led the FDA to remove CDS guidance development from its list of priority guidance documents for introduction in 2017, presumably because Cures provides the needed clarity. However, for CDS software that does not meet the definitions outlined in Cures, there still are questions regarding how it will be regulated. For example, how transparent does the software need to be in order to support independent review by a healthcare professional? And, for that matter, what does transparency mean to FDA? Is it enough to show the calculation used, or does the user need to see every logical decision made by the software? For CDS software processing volumes of data or including multiple nested decision trees, can a healthcare professional reasonably perform independent review?

Despite the enactment of Cures, the FDA still needs to introduce guidance addressing where CDS software will fall under the updated definition of a medical device, and how it will be regulated by the FDA under the Agency’s stratified risk categorization. A CDS guidance would help fill in part of the current void in information.

There still will be situations in which the characteristics of specific CDS products will require discussion with FDA, but guidance will help minimize the number of those scenarios and, further, improve the relevance of information provided to FDA for any needed discussion. Interested parties should press the FDA to make such a guidance available, otherwise we will continue to see lags in CDS software introduction in the U.S.

About The Authors

Scott Thiel, MBA, MT (ASCP), RAC, a Director at Navigant Consulting, Inc., has 30 years of experience in the medical device, health information technology, in-vitro diagnostics, and combination product industries. Scott has led engagements assisting a client with the commercialization of a novel IVD; supporting a Fortune 20 company in the quality remediation; and developing regulatory strategies for medical device manufacturers. He holds a master’s degree in Business Administration from Indiana Wesleyan and a bachelor’s degree in biology and chemistry from Ball State University; Scott also is a member of the Regulatory Affairs Professionals Society.

Jim Williams has over twelve years of experience providing software validation, healthcare compliance writing, expert witness support, and technical and regulatory writing support to organizations, such as life sciences, healthcare, social services, and state government. Jim’s recent projects include reviewing an extensive software documentation packet for an EU firm; serving as a V&V expert and writer on a HDE submission for a U.S. CLIA lab; helping the developer of an algorithm-driven IVD understand FDA requirements; and composing healthcare compliance policies following HHS OIG and FDA regulations/guidance and industry standards. Before joining Navigant, Jim collaborated with a Big Four consultancy on a large-scale software project for eight years.