Meeting & Exceeding User Needs For Wearable, Nearable Medical Devices

By Sara Cinnamon, Amy Hung, and Tobias Silberzahn, McKinsey

Welcome to Part 2 of our article series on wearable medical devices, where we will go into greater depth on the first of three areas critical to creating a successful wearables business: meeting and exceeding user needs.

As described in our overview article, the power of wearables depends on demonstrating their value to users. We introduced a concept called “return on engagement,”1 where patients and clinicians seek sufficient benefits in exchange for using wearable devices. Big-picture messaging such as “improved outcomes” or “healthier life” are not enough to justify continued interaction with devices or platforms. Instead, designers need to understand how they are asking users to engage and participate in the monitoring or treatment process and create useful, seamless interactions – ideally with outputs from the device that are helpful to users and based on a reasonable set of active or passive inputs, i.e., a "positive return on engagement.”1

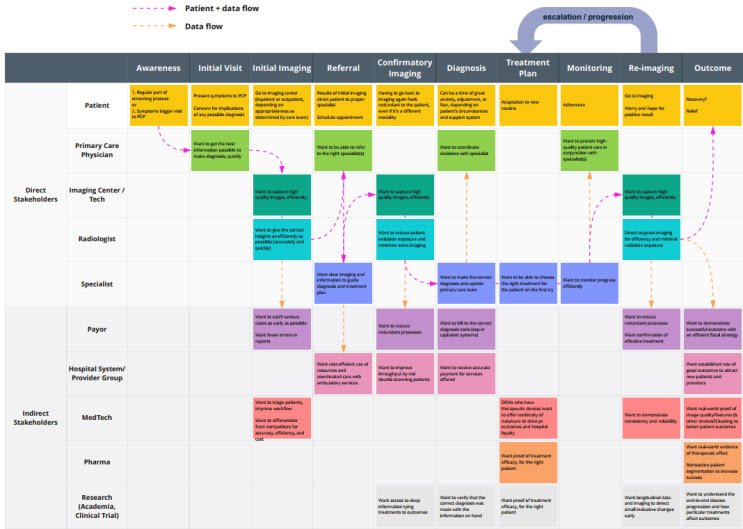

To better understand how satisfying users fits into creating a successful business, consider the framework2 presented in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Building blocks for a successful healthtech business.

Within this framework, meeting and exceeding user needs falls under “Clear value proposition” and “Delightful experience.” Both are needed to satisfy this “return on engagement” equation for a sustained relationship with a device and platform. The first, having a clear value proposition, aids initial adoption by demonstrating how the product addresses a common challenge for both patients and providers. Most people aren’t willing to put up with a frustrating product for long, no matter the promised value. For this reason, it is important to imbue delight in the experience to encourage continued usage. In the following sections, we will provide an overview of the process to discover and codify the needs of patients and clinicians as well as how to provide value and delight via accurate insights that improve care.

Empower Patients In Their Own Care

To deliver value and delight to patients, consider that patients are increasingly interested in understanding their health at a deeper level. Diagnostic and therapeutic devices can deliver information and feedback specific to the user and empower patients to feel more in control of their life and treatment. Designers must ensure these insights are relevant and actionable over the full period of intended usage. For instance, the needs of patients after a life-changing diagnosis, such as cancer, vary from reacting to the initial diagnosis to adapting and actively managing new routines and to quickly becoming experts in their own care. If a product is meant to be their partner throughout, then it should also adapt and grow along with the users.

Discover Users’ Unmet Needs

The process of discovering the unmet needs of users in detail is not rocket science but does require a methodical approach and dedicated resources. After all, this research will provide the basis for many design and business decisions, so investing the time up front will pay off in the long run.

1. Identify Where To Focus

Deciding which medical condition to address can be driven by many factors, including population growth rate, total cost of care, technology available, or lack of innovation in care guidelines. Personal experience cannot be overlooked either, as an anecdote can often be the tip of the iceberg when it comes to identifying market needs.

2. Understand Clinical Implications

Once an area of interest has been identified, reference available clinical guidance to build a detailed understanding, including:

- Biomarkers of disease severity or progression

- Typical progression timelines

- Possible complications and typical speed of onset

- Acute and chronic symptoms

- Typical interventions and their side effects

3. Interview All Stakeholders

Next, interview a representative sample of stakeholders such as patients, caregivers, clinicians, specialists, pharmacists, and payors. Ask open-ended questions to understand their pain points and challenges in managing the condition. Listen to potential users to build both empathy and data-backed insights that inform the future feature set and business model.

4. Take A Deep Dive Into The Patient Experience

As the patient need for usability and comfort is paramount to long-term adoption, spend extra time with five to 10 users to start – and their caregivers as applicable – to better understand the lived experience of managing their condition(s) day to day, including from an emotional standpoint. Build a relationship with users early as collaborators in device development.

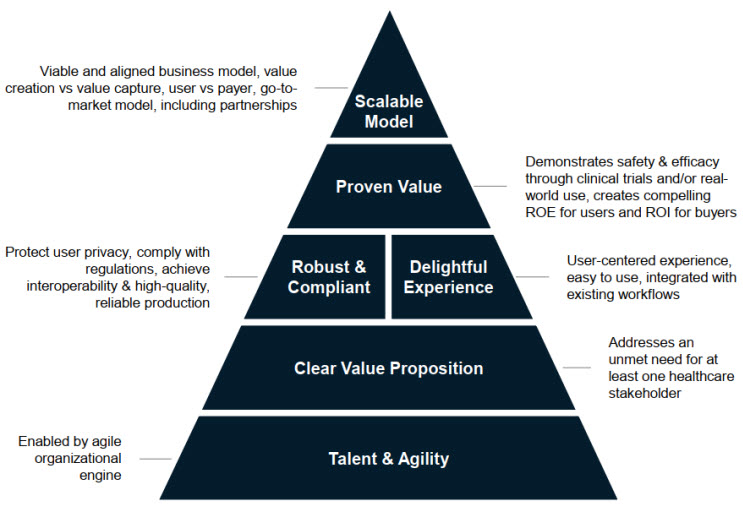

5. Build An Ecosystem Journey Map

Use this information to create a patient-centric ecosystem journey to serve as a touchstone for future decision-making and align incentives across stakeholders. The journey is patient-centric as the wearable will be with them every day and it is their experience to be optimized. The ecosystem is captured to reflect the reality of other influences upon that care journey and can be used to highlight when a feature or service may conflict with the needs of another stakeholder or address the needs of multiple stakeholders at once, generating greater value overall. See an example in Figure 2, below.

Figure 2. Illustrative ecosystem journey for a condition that requires imaging and referral to a specialist for treatment. Click on image to enlarge.

6. Ideate Features And Functions

Summarize the clinical needs and key concerns or complications to detect. Identify aspects that can be measured by existing or developing technology. Additionally, identify aspects that may not be captured by a wearable but could be addressed via a companion app or integration.

7. Jump Into Development

With this fact base in hand, new device development can start in earnest. Identify functional requirements that satisfy user needs. Follow agile principles and test early and often. Prototype in the lowest fidelity possible to answer the question at hand. Continue to test with users to rapidly gain feedback on fit, comfort, and function, addressing the physical and cognitive ergonomics.

Embody Artful Data Collection And Insight Generation

Once user requirements have been defined, the process of collecting data delivering actionable insights can begin in earnest.

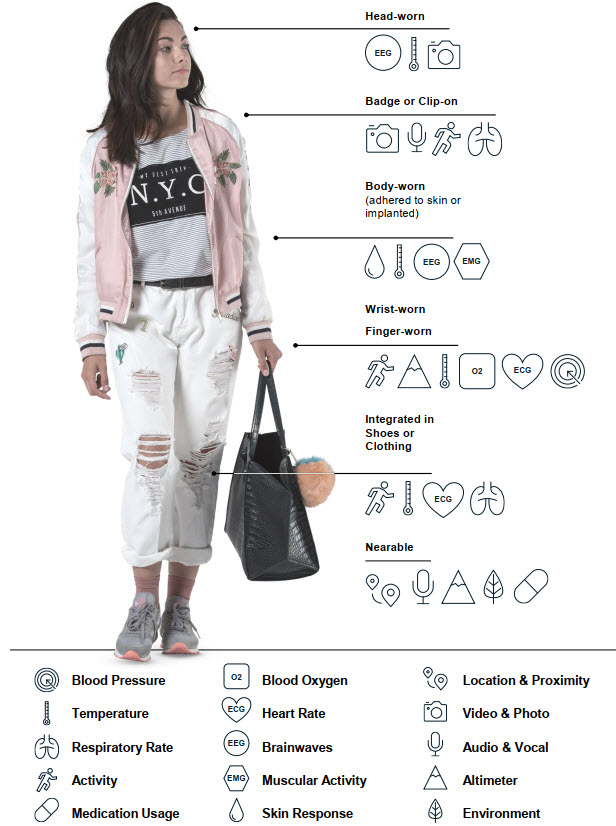

Collecting Data

Devices to gather health metrics can be worn in various locations on the body (wearables), collected from nearby smartphones, thermostats, or other smart devices (nearables), and in some cases devices can be implantable or ingestible.

A variety of general health metric data and insights including behavioral and environmental information can be collected such as:

- Exercise & recovery frequency

- Sleep quality & habits

- Stress & emotional state

- Environmental factors

- Mobility & travel

- Medication adherence & habits

- Dietary habits

These metrics can be captured via a range of devices on or near the body, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Gathering health data from patients and their environment.

Making The Collection Process Easy And Effective

Patients have high expectations for comfort and usability thanks to innovation in consumer devices. If the wearable device is uncomfortable or burdens the user’s daily routines, they generally use it only for a limited time. As a result, device designers may strive to develop smaller, less obtrusive devices with longer battery life. For nearables, they may focus on simple setup and reliable connectivity. Device designers must also understand how physical and cognitive ergonomics affect device operation and data comprehension. Patient interactions with the device should be simple, seamless, engaging, and personal. General guidance for simplicity and seamlessness includes reducing the number of steps required, using consistent language and interfaces, and embedding accessible design into every interaction. Engaging and personal interactions come from enabling choice and customization where meaningful.

Making The Collected Data Useful

When designed with the patient in mind, these devices can deliver many benefits to the user, including reassurance that a professional is monitoring their health metrics and able to deliver care above and beyond what point-in-time visits can offer. We saw this acutely during the early days of COVID-19 when telemonitoring solution Huma was able to monitor patients at home while providing high quality care. AliveCor has provided similar reassurance for users concerned about cardiac health, using community diagnosis to direct patients to appropriate care as well as to augment follow-up in chronic and post-acute care.

Interpretation of data in simple terms and actionable guidance in response to that data provides patients additional insight into and control of their own health. For example, for a patient with asthma using a respiratory monitor that detects early signs of inflammation, at the first signs of a flare-up the device could recommend a strength training day at the gym over a cardio day. For a patient with diabetes, a continuous glucose monitor paired with a meal-tracking function could help patients identify which meals cause them to feel worse, providing direct feedback to make healthy choices in the moment more easily. Similarly, these devices can identify helpful behaviors, such as, for example, showing the positive impact that a walk can have after a meal.

An additional consideration for some use cases is how to include others in the patient’s ecosystem, such as friends and family who may be providing a caregiver or support role. In this case, what information is shared and how it is shared should be treated carefully and with the informed consent of the patient, in addition to following appropriate regulatory guidelines. It is important to understand the nuances of patient-caregiver relationships, including respecting the agency of the patient. Interactions should be designed to support patient understanding and autonomy.

Support Clinical Shift To Prevention Over Reaction With Contextual Data

Now that we have collected a rich set of useful data from patients, we can also deliver value and delight to clinicians. To do so well, we must first understand their current constraints, consider their current workflows, and identify pain points around managing care for many patients. What leading indicators or trends would help them feel more informed when creating care plans? How do they measure progress and outcomes currently? How can wearables support earlier diagnosis through monitoring and provide indicators of disease progression sooner?

Providers are starting to see real value from telehealth broadly. Preferred site of care is rapidly transferring to the home, accelerated by the global COVID-19 pandemic. The flexibility and time savings afforded to both clinicians and patients has been counter-balanced, however, by the lack of reliable data that would otherwise be gathered in person. Wearables enable this collection of real-life and real-time data as patients live their lives. A few examples include MedKitDoc and TytoCare enabling tele-primary care, Nuvo for tele-obstetrics care, and Kinesia for more effective tele-assessments of Parkinson’s.

Once data has been collected, clinicians’ return on engagement can be realized by integrating device readouts into their current systems and workflows seamlessly, as well as by generating insights that they wouldn’t be able to infer otherwise. Devices and associated services that interpret wearable data to reveal patterns and trends can give clinicians a more comprehensive and longitudinal picture of patient health compared with point measurements in the doctor’s office, enabling more efficient disease management. This information is more likely to be considered when it is automatically integrated into the patient record via the EHR. If the provider must log in to a separate system or scan a patient-provided summary, the additional time added to the workflow may not be seen as valuable in a modern practice, unless operational savings can be enabled elsewhere. In the “virtual ward” example by Huma referenced earlier, the tele-monitoring solution reduced time spent per patient from 490 minutes to 280 minutes over 14 weeks.

When data is integrated with the clinician’s primary workflow in a thoughtful manner — e.g., working with existing systems and minimizing additional notifications that contribute to alert fatigue — clinicians can best reap the promise of proactive care delivery to the patient and more efficient resource management among the care team, both of which positively impact the operational efficiency of any medical practice.

Conclusion

Meeting and exceeding user needs is key to adoption and sustained usage of any wearable device in the clinical setting. Companies need to understand the unmet needs of all users in the ecosystem to provide a balanced solution valued by all. The discovery process provides a critical foundation for decision-making and development. The process is not hard, but it is rigorous and requires proper commitment of time and resources. The upside is informed decision-making grounded in user needs that will provide net-positive value to clinical care and outcomes.

Stay tuned for deep dives on delivering rigorous, compliant data and insights for the entire patient care ecosystem as well as crafting a viable business model.

References

- “Return on engagement” coined by Bettina Ryll from Melanoma Patient Network Europe

- https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/life-sciences/our-insights/moving-digital-health-forward-lessons-on-business-building

About The Authors:

About The Authors:

Sara Cinnamon is an expert with McKinsey Design focusing on all aspects of the product development lifecycle, including strategy, design, quality, and manufacturing. Sara also leads the wearable pillar of the HealthTech Network. As an expert practitioner, she combines her background in systems engineering and agile methodology to successfully address complex product and user challenges. She is based in San Francisco.

Amy Hung is a life sciences leader in the McKinsey New Jersey office, where she leads the Global Life Sciences Intelligence Team and co-leads the Global HealthTech Network. With more than 15 years of experience in the life sciences, she has worked with a variety of healthcare companies on growth strategy, capability development, digital and analytics transformations, and org and operating model design. She leads the Annual McKinsey Digital Health Conference, has co-authored a number of papers on digital health and digital in pharma, and spends a good portion of her time speaking with and collaborating with innovators in healthtech. She has a B.S. in chemical engineering from MIT and a dual M.S. in materials science engineering and medical engineering and medical physics from the MIT-Harvard Health Sciences and Technology (HST) Program.

Amy Hung is a life sciences leader in the McKinsey New Jersey office, where she leads the Global Life Sciences Intelligence Team and co-leads the Global HealthTech Network. With more than 15 years of experience in the life sciences, she has worked with a variety of healthcare companies on growth strategy, capability development, digital and analytics transformations, and org and operating model design. She leads the Annual McKinsey Digital Health Conference, has co-authored a number of papers on digital health and digital in pharma, and spends a good portion of her time speaking with and collaborating with innovators in healthtech. She has a B.S. in chemical engineering from MIT and a dual M.S. in materials science engineering and medical engineering and medical physics from the MIT-Harvard Health Sciences and Technology (HST) Program.

Tobias Silberzahn is a trained biochemist and immunologist and works as a partner in McKinsey’s Berlin office, where he is a member of the Lifescience Practice. Over the last 12 years with McKinsey, Tobias has served mainly health tech, pharmaceutical, medical device companies, and ministries of health. He leads the global HealthTech Network, a community of more than 1,000 health tech companies, and he hosts the quarterly HealthTech CEO Roundtable. As part of his work, Tobias also hosts the MedTech R&D Industry Roundtable. Within McKinsey, Tobias also leads the Health & Wellbeing program, focused on sleep, nutrition, stress management and fitness.

Tobias Silberzahn is a trained biochemist and immunologist and works as a partner in McKinsey’s Berlin office, where he is a member of the Lifescience Practice. Over the last 12 years with McKinsey, Tobias has served mainly health tech, pharmaceutical, medical device companies, and ministries of health. He leads the global HealthTech Network, a community of more than 1,000 health tech companies, and he hosts the quarterly HealthTech CEO Roundtable. As part of his work, Tobias also hosts the MedTech R&D Industry Roundtable. Within McKinsey, Tobias also leads the Health & Wellbeing program, focused on sleep, nutrition, stress management and fitness.