New Gene Therapy Could Make Electronic Pacemakers Passé

By Joel Lindsey

Researchers at the Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute in Los Angeles have developed a minimally invasive gene transplant procedure that they say could one day provide an alternative to implantable electronic pacemakers.

“We have been able, for the first time, to create a biological pacemaker using minimally invasive methods and to show that the biological pacemaker supports the demands of daily life,” Eduardo Marbán, director of the Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute and lead researcher of the project, said in a press release issued recently by the institution. “We also are the first to reprogram a heart cell in a living animal in order to effectively cure a disease.”

In their experiment, researchers used a catheter to inject a gene called TBX18 into the hearts of laboratory pigs. In observations of the pigs in the days following the injections, the pigs that received the gene transplants had significantly faster heartbeats when compared to pigs that did not receive the genes. The increased heartbeats remained consistent for the entire 14-day study period.

“This work by Dr. Marbán and his team heralds a new era of gene therapy, in which genes are used not only to correct a deficiency disorder, but to actually turn one kind of cell into another type,” said Shlomo Melmed, dean of the Cedars-Sinai faculty.

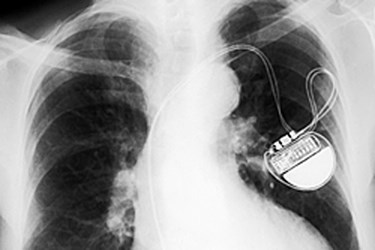

Researchers involved with the project said that the new technique could provide a safer and more effective way to treat heart disorders in a number of patients. In particular, using gene injection to influence the development of heartbeat-generating cells could significantly reduce the need for implanted pacemakers, which can often lead to complications or the need for additional surgeries.

Similarly, the new gene therapy could provide a way to treat babies born with heart disorders who are too young for the invasive surgeries necessary to implant a pacemaker device.

“Rather than having to undergo implantation with a metallic device that needs to be replaced regularly and can fail or become infected, patients may someday be able to undergo a single gene injection and be cured of the slow heart rhythm forever,” Eugenio Cingolani, director of Cedars-Sinai’s Cardiogenetics-Familial Arrhythmia Clinic, said in a news article published by Reuters.

Details and results from the research team’s tests have been published in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

According to Cedars-Sinai’s press release, Marbán predicted that the gene therapy could be ready for human clinical studies in about three years.