Pioneers Recall The "Good Old Days" Of Device Development

By Bob Marshall, Chief Editor, Med Device Online

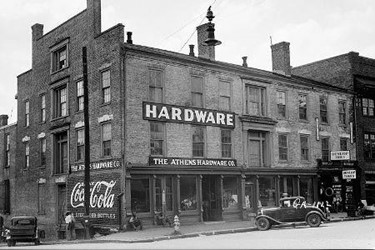

I love “old school” hardware stores. My best Saturdays, when I’m not out fishing in my little boat, are spent with a pencil behind my ear and a home improvement project to conquer.

But, inevitably, one or more trips to the store will be necessary, no matter how well I plan for the project. I am fortunate to live in a large town north of Pittsburgh that has both a Home Depot and a Lowe’s Home Improvement Center, but I often choose to drive to a neighboring small town with two “mom-and-pop” hardware stores. There’s no traffic, they know my name, and they don’t ask me to join their rewards program. Further, I can find the items I am looking for in the smaller footprint of the store, there is no pressure to buy, and I am helped by friendly, knowledgeable people.

I know I sound like an old guy — and I am getting there — but what does this have to do with medical devices? The thoughts of simpler times rushed to mind recently when I had the opportunity to interview Dr. Stephen Heilman and Dr. Mark Wholey, who together developed the first flow-controlled angiographic contrast injector 50 years ago. These two medical pioneers invented a device that satisfied a previously unmet clinical need, created a company called Medrad (now part of Bayer), and spawned a revolution in medical imaging. Evidence of their impact can be seen in the 10 million contrast-enhanced MRI procedures performed in the U.S. in 2017.

In the early 1960s, Heilman, an emergency room physician, saw an early coronary arteriogram and recognized the need for better tools to visualize injured vessels, as well as provide meaningful treatment for heart attacks and strokes. He partnered with Wholey, who was trained in angiographic procedures.

“Building a disposable syringe that could handle really high pressures, and including a feature that would control the flow of the contrast media — [ensuring] correct flow of contrast media into the site of interest to image — were the main innovations, amongst other features that were part of our first flow-controlled injector," Heilman explained.

Wholey, who was trained at Case Western University and the Mayo Clinic, added: “At that time, percutaneous angiography wasn’t being done; most angiographic procedures were done surgically. However, Seldinger in Sweden was describing a percutaneous method, so I applied for a NIH fellowship with the indication that, when I came back the U.S., I would train other physicians.”

“When I was in Sweden, a lot of the percutaneous procedures were done with just a needle and a doctor basically standing on the table, and through this tube pulling down with their hands to create some pressure to introduce fluid into the arterial system,” Wholey continued. “When I came back the U.S., it was uppermost in my mind that, if I was going to do anything, I would get involved with someone developing an injector. I have always been device-oriented, and Steve had always wanted to run a company, so when I met Steve, I suggested that developing an injector was an ideal situation for us.”

Initially, Heilman and Wholey developed a hydraulically-controlled injector. But they realized, no matter how good the hydraulic system was, it would have a leak, so they quickly switched to an electric motor-driven system.

“The injector was flow-rate controlled, which was important because the flow in the carotid artery to the brain is totally different than the flow in the abdominal aorta, or in the legs, or in the coronary arteries,” explained Wholey. “So, with a flow-rate injector, we were able to control the flow to the different vascular structures in the body. That’s critical, because we’re not interested in injecting by hand with whatever pressures we were generating to the carotid arteries and the brain. By regulating the flow control, we were able to create a whole safety environment for the injection.”

Wholey recounted the first use of his and Heilman’s injection system at the VA hospital in Pittsburgh.

“We had just finished developing the injector, but had never tested it clinically in patients. At that time, the contrast media was rather painful, because it was ionic. When we injected the ionic contrast media into this first patient, he almost stood up on the table screaming,” Wholey recalled. “One of our engineers thought we had killed the patient, but it was only a short amount of time before the contrast media washed out and everything went back to normal. That was our first exposure to the ionic contrast media in a high-level injection.”

Taking this walk down memory lane with Heilman and Wholey was quite interesting, and it made me think more deeply about the process of medical device development 50 years ago. One has to remember that these pioneers were bringing new technology to the medical device marketplace roughly a decade before the Medical Device Amendments of 1976 (also called the Medical Device Regulation Act) were enacted. I couldn’t resist asking Heilman and Wholey about their perspective on current day regulations. Heilman deferred to Wholey, who had some strong feelings on the topic.

“Steve and I both grew up in the honeymoon era of medical device development. In those days, we didn’t have IRBs and FDA regulation. We were free to think in terms of devices and using our best judgment. We could develop the devices that we thought were most appropriate without all of the unreasonable limitations now,” Wholey replied. “I think over-regulation has killed new device development in this country. I am a serial entrepreneur, and every single device we develop in the U.S. goes to Europe or Argentina for clinical studies. Getting things through FDA first — forget it. Eventually, we have to come back to seek clearance or approval in the U.S. because the revenue is here, but the processes are painfully slow.”

Heilman added, “We have a highly established, highly developed regulatory system in the United States. There’s a plus and a minus. The minus is it adds substantial cost and time to market; on the other hand, it does guarantee certain controls. Certainly, any product that’s in the marketplace is highly documented and consistent. It has got to be the same, product to product, within a given model. But the costs are very high in this country.”

I came across some corroborating perspective during my research for this article. Attorney Peter Barton Hutt, who left private practice in 1971 to become chief counsel for FDA, was given the primary charge of drafting the legislation that would become the Medical Device Amendments of 1976. Barton shared the following generalization in a 1996 interview:

“From their enactment in 1976 until the early 1990s, the Medical Device Amendments’ implementation was quite faithful both to the specific language and to the spirit and intent of the legislation. In the past five years, this has changed dramatically. What FDA is doing in many areas today is both outside the statute’s specific language and contrary to Congress’s original intent in enacting the statute.”

Ah, the good old days. I think I’ll just roll up my sleeves, put a pencil behind my ear and head over to my hometown hardware store. Better yet — I’m going fishing!