3 Rules For Defensible Compliance: Applying Risk Management To Regulatory Decisions

By Thomas Bento, Nihon Kohden America

“Defensible compliance” can’t be a new concept for those of us who have spent any amount of time in a regulated space. Defensible compliance is, at its core, the consideration of risk management in every regulatory decision. The concepts discussed in this article will help you and your organization begin to think and act only after considering the risk associated with a decision, which will give you greater confidence in decision-making.

It didn’t take me long working as a regulatory consultant to find the common thread running through the QA/RA fabric of all manufacturers: A propensity to overcomplicate what could be a simple process, that of reducing regulatory and business risk. Simplification “leans” the internal process, reduces risk, and puts the manufacturer in a more defensible regulatory position.

Years ago, I was reading through FDA’s guidance General Principles of Software Validation, or GPSV, which states “… activities, tasks, and work items should be commensurate with the complexity of the … design and the risk associated with the … specified intended use.” This logic can easily be applied not only to validation of software, but to how we manage all aspects of regulatory business activities. For example, 95 percent of the time, the answer to the common question, “How much supporting documentation is enough to satisfy regulatory expectations?” is discovered through understanding the risk and complexity associated with a device.

Consider the following equation, where R is risk, C is complexity, and Ri is rigor:

- More detailed documentation to support decisions = (> R+ > C = > Ri)

- Less detailed documentation to support decisions = (< R+ < C = < Ri)

The greater level of rigor is applied to the greater level of risk. This concept is adopted in FDA’s guidance that details supporting documentation for 510k submissions, Guidance for the Content of Premarket Submissions for Software Contained in Medical Devices. This rule is applicable to validation, procedural complexity, requirement definition, rationale statements, etc. Once you understand and define the risk and complexity of your own process, you can create a method to quantify it, and then define your own levels of rigor.

There are three simple rules to help your company in this direction: simplify, educate, and own it.

Rule #1 - Simplify

Don’t overcomplicate a process that can be simplified. It’s ironic that, with all the technology available to simplify our lives, we instead use that technology to squeeze more into a day than was ever thought possible. This multi-tasking leads to an overcomplicated state; it now takes conscious effort to simplify. In the regulated space, there are opportunities at every corner to over-interpret the QSR and other regulatory requirements, making what could be a simple process into a complicated mess. Let’s take a closer look at how this applies to automated process validation.

About 98 percent of medical device manufacturers for whom I have consulted interpreted the requirement for automated systems validation (21 CFR Part 820.70(i)) differently from one another. This regulatory clause in the QSR requires the manufacturer to “validate computer software for its intended use according to an established protocol,” and it is intended to validate automated systems that are used as part of production or the quality system. So, this requirement applies to those systems that have a “predicate requirement” found in the QSR (i.e., document control, training, statistical data, traceability and ID, etc.).

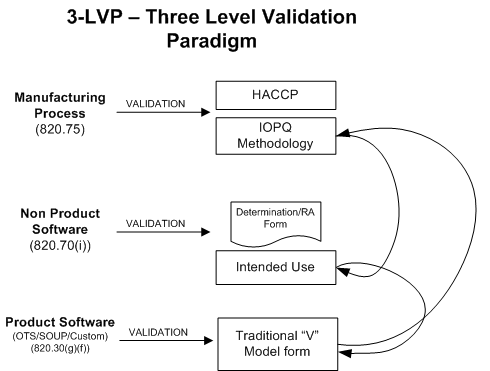

Thus, if I have an automated system that manages my document control, I must validate that system, because it can indirectly impact the quality of the product. Specifically, the requirement states that I must “validate my software for its intended use.” Why, then, do many manufacturers assume that it is required to follow an installation, operational, and performance qualification (IOPQ) paradigm for validation, or to introduce the rigors of product validation? These steps are not necessary to satisfy our regulatory obligation, and they introduce complexity and compliance risk. To illustrate this point, below is a graphic of how different validation techniques are inappropriately applied.

I subscribe to the out-of-box thinking paradigm outlined in AAMIs TIR 36 – Validation of Software for Regulated Processes. This approach adopts a critical thinking approach to validation, rather than a checklist mentality: It encourages validation based on the risk of the process. Why not apply a simple approach to validating the software by defining a set of requirements, testing each of those requirements, and then maintaining records of that testing as evidence of compliance?

Rule #2 - Educate

The best way to equip both yourself and your organization with the information necessary to make intelligent compliance decisions — and to be confident in those choices, equating to defensible compliance — is education. Stakeholders throughout the development process should be familiar with the most up-to-date training regarding applicable regulatory requirements (CFRs), FDA guidance publications, and your organization’s proprietary product lines. When making regulatory decisions, a well-thought-out, structured rationale and justification, based on the risk and complexity of the device, will put the organization in a defensible position.

Furthermore, education and training should not be limited to regulatory requirements, but should extend to adoption of industry best practices through FDA’s acknowledged consensus standards and applicable guidance documents. In the case of 21 CFR Part 820.70(i), AAMI TIR 36 is an excellent choice; in the case of software development lifecycle processes, look to IEC 62304:2006.

Rule #3 – Own It

The individuals that execute these processes must “own” them! This cannot be emphasized enough. In every collaborative meeting conducted at my company, the points of proactivity and process ownership are discussed. When given stewardship of key critical processes — such as complaint handling, corrective and preventative actions (CAPA), nonconforming products (NCP), and design control — it’s of the utmost importance to understand all aspects of our duty and responsibility. These tie into the previous point of being sufficiently trained to perform the appropriate duties. How can I effectively defend a process if I don’t have sufficient knowledge of the process and expectations? Ownership of the process is more than just knowledge of how the process is proprietarily defined within your organization; it extends to the attitude of the individual.

Everyone has experienced, at some point, a profound passion for work or recreation, embracing wholeheartedly a sport, hobby, or profession. As you devote your time and focus your mental agility to an activity, you will find that new creative solutions begin to creep into the methods of how you apply yourself to that activity. This is the essence of owning the process. Allowing, and encouraging, this to occur will ultimately bring out the best in people, as well as ensure a process that is more valuable and effective.

Good, Better, Best

GOOD regulatory decisions satisfy the short -term regulatory goals of the organization, but they lack the substance of a more well-thought-out solution. Such decisions consider risk only when assessing the product, and they tend to come from a checklist-thinking organization, rather than one thinking outside the box.

BETTER solutions have a history of satisfying compliance to requirements, but they do not always cultivate an environment of confidence in regulatory decision-making and continuous improvement.

The BEST regulatory decisions are founded on all parties understanding and being able to demonstrate the conclusion of risk and complexity. The organization understands the regulations and the explicit requirements related to their product; they understand intimately the risk associated with all aspects of the product, as well as the production process, to enable control of the products’ design and development. For every compliance question asked, the risk of hazard and complexity is considered. Regulatory and product confidence is very high within this company!

About The Author

Thomas Bento is SVP of quality, regulatory, and clinical assurance for Nihon Kohden America. He has over 15 years' experience in regulatory compliance for medical device manufacturing, focusing on a simplified, risk-based approach to product safety, quality systems, and regulatory affairs from around the world. Prior to joining Nihon Kohden, Thomas consulted for Certified Compliance Solutions and worked within industry for companies like Mitek Systems, Hewlett-Packard, Pulmonetic Systems, and Edwards LifeSciences.