SaMD PCCP Implementation Beyond AI/ML: Considerations & Challenges

By Yu Zhao, Rene Hardee, Randy Horton, Ashley Miller, Michael Iglesias, Roma Williams, and Jaden Maloney

This is the third and final installment in our three-part article series on postmarket change controls and implementing a Predetermined Change Control Plan (PCCP) for Class II Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) products beyond artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML). If you missed the first two articles, they are:

- Article 1: Medical Device Postmarket Change Controls & FDA 510(k) Software Modification Guidance

- Article 2: Deciphering New U.S. Laws Around Predetermined Change Control Plans

Considerations For PCCP Changes For Non-exempt Class II SaMD Products

The PCCP is a new mechanism that allows the FDA to exempt certain planned changes from the premarket notification or the premarket approval submission requirements if those changes are consistent with the PCCP authorized by the FDA. Prior to FDORA, such changes would otherwise require 510(k) or PMA submissions.

Therefore, it is not necessary for manufacturers to include any planned change that would be assessed as a document-to-file under the existing regulations and FDA guidance, as such minor changes do not require 510(k)s, PMAs, or PMA supplements without a PCCP.

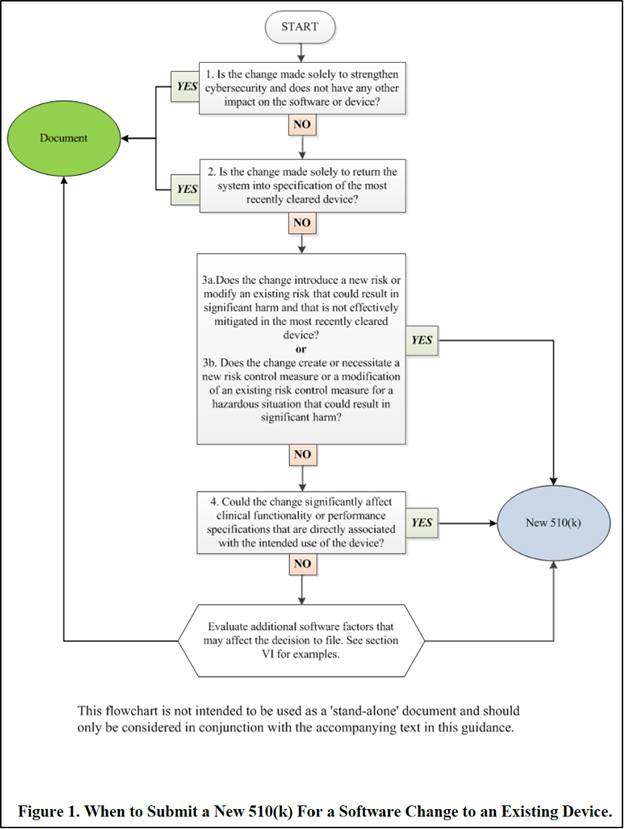

Specifically for non-exempted Class II SaMD software, planned changes that would lead to a “document” decision in the same decision-making flowchart from the 510(k) software modification guidance (illustrated below) are not suitable for the PCCP. Manufacturers can simply go through the change control process, assess the impact of the change, and properly decide on a document-to-file regulatory pathway before implementing the change, without a need for such future changes to be included in the PCCP for pre-authorization by the FDA.

Figure courtesy of the FDA’s guidance document

For the same reason, suitable changes to be included in a PCCP are the type of future changes that would fit in one of the decision boxes in the above flowchart and result in the decision to file a new 510(k).

Since FDORA does not change the requirements for 510(k) devices, the FDA expects that any changes included in a PCCP for a 510(k) device must be limited to modifications that do not affect the device’s safety or effectiveness. Software with these modifications must also be substantially equivalent to the last cleared version of the software or the last version granted through the de novo classification process. We offer the following suggestions to both device manufacturers and the FDA about how to evaluate which changes might be a good fit for this new regulatory state, and which might be poor fits.

Section VI of the 510(k) software modification guidance includes the change categories listed below. The FDA presented these as “additional factors to consider” without indicating the appropriateness of a new 510(k) submission, since the potential impacts from these categories of software changes vary greatly and are difficult to be summarized in a flowchart format. If your planned software changes fit into these categories, they could be good candidates for PCCP changes as long as you describe in detail in the PCCP your change impact assessment process, performance criteria, etc.:

- infrastructure

- architecture

- core algorithm

- clarification of requirements

- cosmetic changes

- reengineering and refactoring

Next, we suggest that manufacturers focus on decision boxes #3 and #4 in the flowchart in Figure 1 above when evaluating the appropriateness of potential changes for inclusion in a PCCP. Specifically, manufacturers should carefully review the 510(k) software modification guidance’s Appendix A software modification examples, especially software changes that lead to a new 510(k) based on flowchart questions 3a, 3b, and 4. Not all such changes are good candidates for the PCCP, but some could be with an appropriate control plan presented in the PCCP and implemented by the manufacturer.

A SaMD software change can lead to changes in software labeling, performance specifications, or wireless communications, for example. To properly decide whether or not a new 510(k) is required for a proposed software change, in addition to using the 510(k) software modification guidance, a manufacturer should also refer to the 510(k) device modification guidance (i.e., Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff, Deciding When to Submit a 510(k) for a Change to an Existing Device, October 23, 2017).

Similarly, we suggest that a manufacturer carefully review Flowchart A (labeling changes) and Flowchart B (technology, engineering, and performance changes) in the 510(k) device modification guidance and examples of relevant changes (in Appendix A) that currently lead to decisions to file a new 510(k) to determine whether there are appropriate change types that can be included in the SaMD PCCP.

Appropriate Components Of An Effective PCCP For Non-exempt Class II SaMD Products

It’s important to keep in mind that a PCCP is a request to FDA to pre-authorize certain future changes to a medical device without lowering the standard for safety, effectiveness, or substantial equivalency. Making PCCP determinations is not something that we expect FDA reviewers to take lightly.

To improve the chances of FDA authorization for a PCCP, in addition to selecting appropriate changes or change types to be included in the PCCP, it is crucial to provide a comprehensive and transparent explanation of the change control process in the PCCP. The PCCP should demonstrate that the changes will be well-understood, well-controlled, thoroughly tested, and properly implemented to ensure safety and effectiveness. We suggest that an effective predetermined change control plan for non-exempt Class II SaMDs could include the following key components:

- Software description

The PCCP could include a detailed description of the product, including software functions, features, and key UI designs, architecture charts, interface specifications among different modules if the software uses a modular design, and technologies used (e.g., computer vision, machine learning (ML), or deep learning (DL)).

- Types of planned future changes covered by the PCCP

The PCCP could specify the anticipated or planned future changes that are covered (i.e., in scope) by the proposed PCCP, i.e., future changes for which the manufacturer is seeking pre-authorization from the FDA through the PCCP.

Equally important, the manufacturer could indicate future changes that are explicitly excluded (i.e., out of scope) for the proposed PCCP.

Detailing specific in-scope and out-of-scope change examples can help the FDA understand the scope and the boundaries of the proposed PCCP.

We also note that based on past experience, it is not uncommon for the out-of-scope list to be longer than the in-scope list.

- Change control process description

The PCCP could describe the manufacturer’s change control process in sufficient detail, including which functional groups are involved, impact assessment including the risk assessment process, how the proper level of verification and/or validation testing is decided, how to determine whether a proposed change is or is not consistent with the FDA-authorized PCCP, software change deployment and postmarket performance monitoring and control plan, etc.

A key element of the change control process for PCCP is the decision-making process and criteria for deciding whether each proposed future change is within the scope and consistent of the PCCP. Such decision-making criteria may include clinical or functional performance criteria. This adds to the process described in our first article in this series, but Step 4 assessing whether a new 510(k) is required also takes into consideration PCCP.

- Labeling

The PCCP could describe whether, and under what circumstances, new labeling is required for safe and effective use of the modified software and how the new labeling is presented to the users. For example, such circumstances could be when a change requires a new warning, affects instructions for use, or results in significant user interface changes. The updated labeling should be presented in a clear and transparent way for users to understand the changes and the potential impact.

- Post-deployment control plan

The PCCP could include the plan for real-world performance monitoring post-deployment, and the criteria and process of reverting the change and/or notifying users if the modified SaMD does not function as intended.

Areas That Require Further Clarity

We have included some points that would benefit from clarification regarding the PCCP to encourage ongoing discussions among the medical device industry, the FDA, and other stakeholders. We believe that these points are important to consider as the FDA and the medical device industry jointly tread onto the new terrain of implementing PCCPs. Continued discussions and collaboration between all stakeholders will be necessary to address these points and ensure the effectiveness and sustainability of the PCCP over time:

- In the proposed PCCP submitted to the FDA, does the manufacturer need to provide any supporting evidence to build agency trust?

- How should the manufacturer and the FDA assess the potential impact of evolving standards and regulations on the already-approved PCCP?

- How will the FDA verify proper implementation of the PCCP? For example, should the FDA set up a special audit program outside of current for-cause and routine surveillance inspections?

- Should there be an expiration date for a PCCP? Or should the FDA ask the manufacturer in subsequent premarket submissions after the original PCCP is authorized to provide an updated PCCP or a justification why the existing PCCP will continue to be effective with the modified device?

- Once approved, can a PCCP be suspended or rescinded by the FDA and, if so, under what circumstances?

- FDORA covered the PCCP but not the software precertification program. What are the relationships between the two programs? What is the current status of the software pre-certification program?

Note that in September 2022, the FDA issued a final report1 discussing the results of its software precertification program, concluding that while rapidly evolving medical device software technologies could benefit from the new regulatory framework, such a new paradigm would require federal legislative action. However, with the PCCP approved under Section 3308 of the FDORA, there may be an opportunity to modify the software precertification program and potentially implement it under the PCCP framework. This could potentially involve incorporating some or all five culture of quality and organizational excellence (CQOE) principles (product quality, patient safety, clinical responsibility, cybersecurity responsibility, and proactive culture) as a part of the PCCP.

Reference

1. https://www.fda.gov/media/161815/download

About The Lead Author:

Yu Zhao founded Bridging Consulting LLC, a consultancy dedicated to assisting AI startups and medical device companies in achieving innovation and regulatory compliance, in 2020. He has more than two decades of experience in the life sciences and technology space, and specializes in medical device regulatory, quality, and clinical affairs. His clients range from startups to large industry companies. During his tenure at Medtronic, he led regulatory affairs departments for multi-billion-dollar business units.

Yu Zhao founded Bridging Consulting LLC, a consultancy dedicated to assisting AI startups and medical device companies in achieving innovation and regulatory compliance, in 2020. He has more than two decades of experience in the life sciences and technology space, and specializes in medical device regulatory, quality, and clinical affairs. His clients range from startups to large industry companies. During his tenure at Medtronic, he led regulatory affairs departments for multi-billion-dollar business units.

Contributing authors are Rene Hardee, director of regulatory and program management at MedSec; Randy Horton, chief solutions officer at Orthogonal; Ashley Miller, director of regulatory affairs at Digital Diagnostics; Michael Iglesias, global quality advisor at Roche; Roma Williams, student at the University of Miami; and Jaden Maloney, student at Johns Hopkins University’s Whiting School of Engineering.