Shark Skin Inspires Antimicrobial Surfaces

By Chuck Seegert, Ph.D.

In order to combat superbugs, alternative methods of preventing infection have become paramount. A recent study from researchers at Sharklet Technologies shows significant promise and may provide a tool in the fight against hospital-based infections.

Hospital-based infections are a significant concern to many patients and healthcare workers. Germs abound in hospitals, and patients are particularly vulnerable due to other diseases they may have. Combine this with certain antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria, and the problem only worsens.

Instead of relying on antibiotics after an infection has taken hold, a recent study published by a team at Sharklet Technologies introduces a novel preventative approach. While cleaning surfaces to remove bacteria is a mainstay of hospitals, there are drawbacks and shortcomings to this approach, including the toxicity of the chemicals and human error.

The team’s preventative approach involves changing hospital surfaces to make them less amenable to bacterial attachment by mimicking a texture similar to shark skin. Used in conjunction with existing methods, the new surface design could help reduce hospital-based infections.

"Shark skin itself is not an antimicrobial surface, rather it seems highly adapted to resist attachment of living organisms such as algae and barnacles,” said Dr. Ethan Mann, a research scientist at Sharklet Technologies, in a recent press release. “Shark skin has a specific roughness and certain properties that deter marine organisms from attaching to the skin surface."

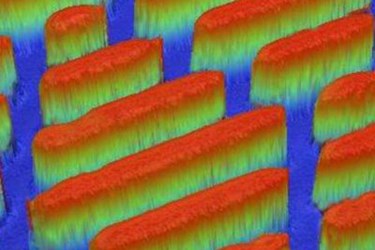

The Sharklet micropattern was based on the microscopic surfaces seen on shark skin, a surface that prevents marine organisms from attaching to the shark. Studies performed for more than decade have shown that this pattern is more effective than other micropatterns, like pillars or channels, at preventing organisms from attaching in nutrient-rich environments, according to the study. Essentially, the size and spatial positioning of the microscopic features make it difficult for bacterial attachment.

"The Sharklet texture is designed to be manufactured directly into the surfaces of plastic products that surround patients in hospital, including environmental surfaces as well as medical devices,” Mann said in the press release. “Sharklet does not introduce new materials or coatings — it simply alters the shape and texture of existing materials to create surface properties that are unfavorable for bacterial contamination."

In their study, the Sharklet team tested their micropattern in a setting that resembles a hospital environment. Using methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA and MSSA), the researchers contaminated surfaces in a way that replicated the effects of sneezing, touching, and spilling contaminants on surfaces. MSSA transmission was reduced by 97 percent on the surfaces with the Sharklet micropattern when compared to copper, a common antimicrobial surface. MRSA was also reduced by an impressive 94 percent.

Prevention of hospital-based infections continues to gain attention as the threat of antibiotic-resistant organisms increases. Treating hospital surfaces is an approach that continues to be studied as a method of prevention. In addition to micropatterning, other research teams have looked at using light-activated materials for eliminating bacteria from high traffic surfaces.

Image Credit: Mann et al.