Take The Narrow Path To Wide Adoption — Here's Why And How

By Mike Fix, Navigant

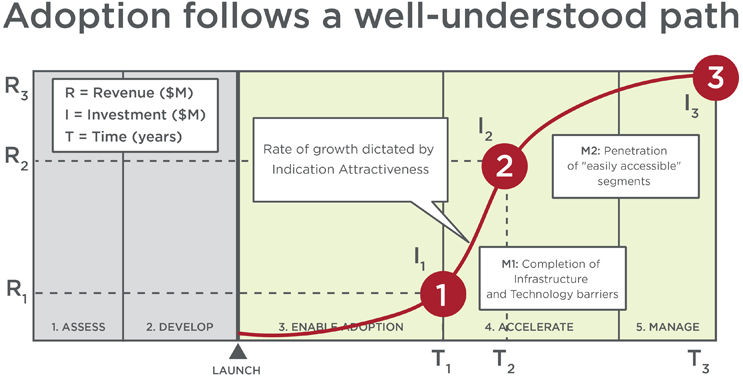

After spending thousands of dollars to develop, test, and approve a product, medtechs tend to focus their commercialization strategies on the whole patient pool, thinking it’s the best bet for significant return on investment. While that approach seems logical, it rarely manifests in practice. The average medical technology takes 10-15 years to be broadly adopted — after being published as a standard of care in practice guidelines. Most technologies falter long before then.

So, what is the best path to market penetration? Ironically, it’s usually a narrow one. Segmenting patients, providing physicians with guidance on which ones your technology suits best, and clearly stating expected outcomes helps to drive use, preference, and — eventually — increased adoption rates. It also helps you align your resources and investments realistically to foster adoption.

Consider this example: a startup originally estimated the market size for its breakthrough technology to treat uterine fibroids at 75 percent of all women. But, further research revealed that figure to be significantly inflated and vague, as it failed to consider several critical factors. In fact, the most compelling opportunity lay in the large pool of insured U.S. women who regularly sought preventive ob-gyn care — 24 percent of the addressable population, representing $428 million in annual revenue by 2028. This insight was based on patients’ condition severity, desire for fertility, fibroid location, provider access, and payer coverage, as well as the company’s modest sales infrastructure.

Had the manufacturer launched broadly, they risked weak clinical outcomes, reduced physician confidence in the technology, and failing investor expectations. Here’s why.

Rules Of Engagement: Adoption And Penetration

The average clinician takes no personal stake in helping a technology succeed or fail; their only stake is in providing positive outcomes for their patients. To convince them it’s worth using a new innovation in favor of what they already know works, you need to motivate them through belief that the technology will deliver:

- Improved patient outcomes, safety, quality of life or comfort

- Improved efficiencies, economics, or time savings

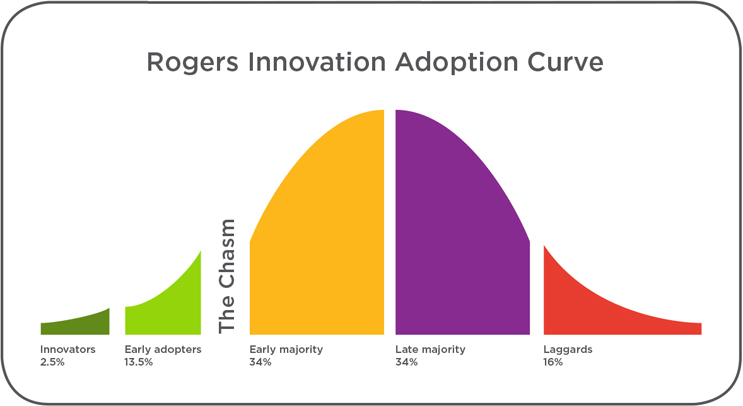

Adoption follows a well-understood path to standard of care. Most technologies fail to get past the early adopters (about 15 percent) through the classic “chasm” to the early majority, which serves as the gate to the rest of the market.

The difference between each adoption group is its intrinsic beliefs about both the status quo and what the new technology offers. The innovators and early adopters are driven primarily by the idea and promise of the new technology. Therefore, they need little evidence or guidance on patient selection; they want to figure it out on their own, and often believe other clinicians think like they do. In contrast, the “early majority” needs hard evidence and a proven patient selection algorithm. And, importantly, the “late majority” and “laggards” share the early majority’s needs, plus personal experiences that give them confidence in the new technology.

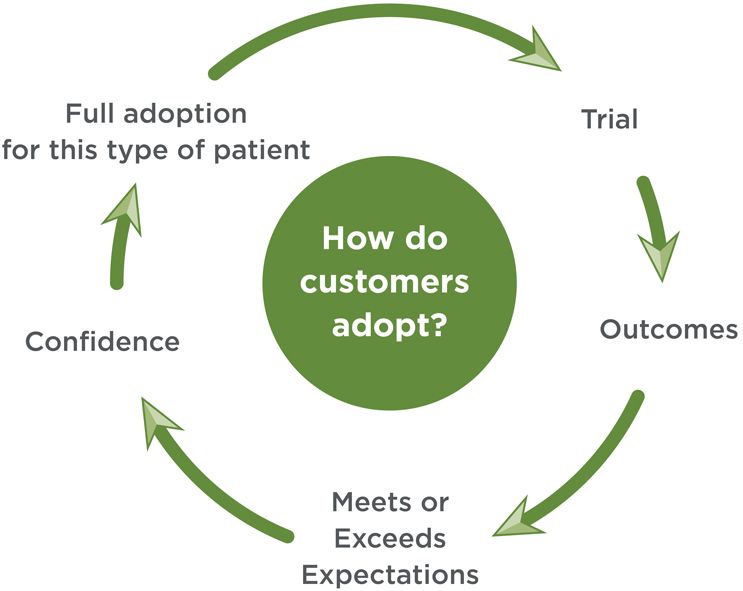

Consequently, convincing each subsequent stage of adopters requires more evidence and validation of a new technology’s clinical and economic value proposition, along with a roadmap identifying the best patients. If no guidance is provided on best-use case scenarios (i.e., patient segments most likely to experience a positive outcome from the treatment option), physicians usually apply the therapy to patients as a last resort. As a result, outcomes will be questionable, at best, and often negative — which ultimately diminishes adoption rates.

However, if a pipeline of evidence and patient selection guidance is provided, then early stage adopters will gain confidence, share their experiences, and provide useful insights. These insights will help the manufacturer make relevant modifications to the product and/or resolve other adoption-related barriers, enabling the manufacturer to continue building confidence among physicians, and to roll the therapy up and over the adoption curve.

Once physicians are confident in a technology’s value proposition for a certain segment, they will more readily expand to a fuller indication. Each positive step accelerates and deepens market penetration. Full adoption occurs when behavior change fully transitions.

The clearer the benefit and better the results, the faster the adoption.

Patient Segmentation Considerations And Factors

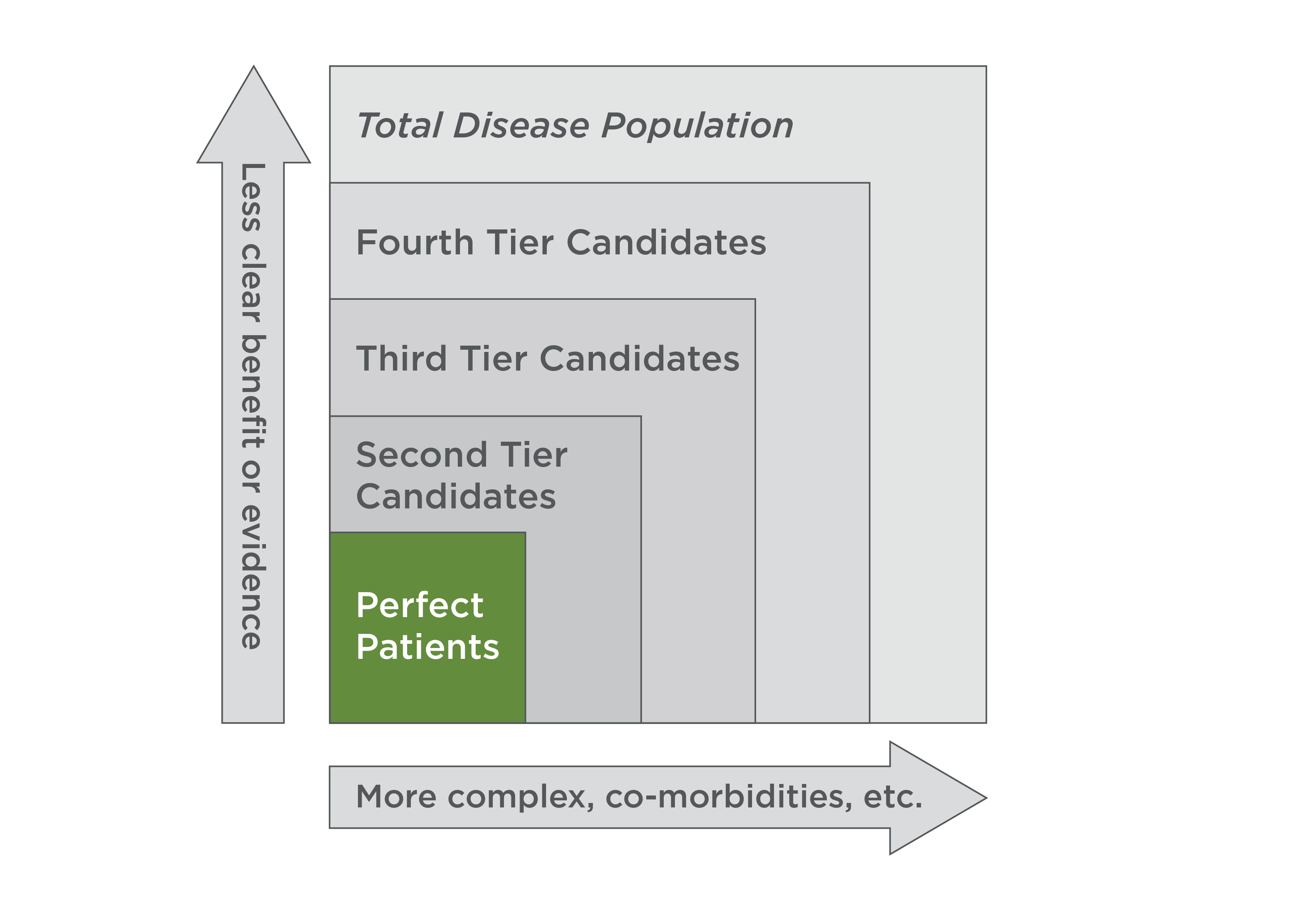

The goal of patient segmentation is to gain granular insight into the differential technology benefit and adoption potential among distinct groups. By strategically organizing heterogenous patients into more homogenous groups, based on the benefit of the new technology vs. standard of care, you can more accurately estimate the true market potential of a technology, anticipate and create strategies to overcome potential barriers to adoption, and better manage expectations across stakeholders.

A series of objective, identifiable, and predictable factors are used to categorize segments. While these factors vary depending on the technology and condition, they often include:

- Disease — Characteristics that impact the urgency and potential benefit associated with treatment vs. the current standard of care, including disease severity, specific pathology, symptom status

- Patient — Characteristics that inform response, potential benefit, or burden of the disease, such as age, gender, comorbidity burden, frailty

- Technology — Disease, pathologic, or anatomic features that inform the technology response rate, or selection decision

- Economic — Ability of patients to pay for their share of the cost can be an important driver for technologies with a high upfront cost or ongoing payments over time.

“Actionable” segmentation identifies patients for whom therapy will provide lesser or greater benefit, and notes where patients will be in the healthcare system. Adoption rates will vary significantly across different patient segments. As such, it’s important to identify “perfect patients” (i.e., those representing the group for whom a specific therapy option will offer the greatest consistent benefit). They are the beachhead target to drive to standard of care. Subsequent indications are based on logical sequencing of how clinicians would think about patients.

Consider the following three examples, wherein research and analysis performed after the “potential” patient pools had been determined uncovered a series of unavoidable factors that significantly reduced the potential patient pools and enabled segmentation:

- One startup’s leadership team believed a vast U.S. market existed for its innovative migraine therapy, and planned to target the 11 million Americans who suffered from the condition. In this case, the 11 million Americans were trimmed to 8.5 million after evaluating exclusion factors, including condition severity, compliance, and income.

- A market-leading device manufacturer with a novel technology platform instinctually believed its technology could be applied generally to obstetric and oncology patients. In this case, the most compelling opportunity lay in smaller patient segments within one major treatment segment: trauma.

- A global medtech company hoped its new technology could be launched to treat obesity in 80 million U.S. patients, and millions more globally. In this case, the 80 million narrowed to only seven million. Exclusion factors included people aging out of obesity, fewer patients than anticipated feeling enough discomfort to be motivated to seek treatment, and limited reimbursement that resulted in a prohibitive cost barrier.

While each of these cases still proved to be fruitful endeavors and strong market opportunities, the original patient pool estimates were grossly misleading. Data-driven patient segmentation gave each company a patient segment to target, helping each company to prove its value and to carve out a place in the complex, existing clinical pathways that are extremely hard to disrupt.

Risks Of Not Segmenting

Without clear and actionable patient segmentation, there exist many risks throughout product development, market development, and commercialization, including:

- Diluted results in clinical trials, which can dampen potential interest in the technology, and be detrimental to practical outcomes, soiling physicians’ organic experiences.

- Regulatory bodies narrow your indication because it’s too broad as initially pitched, which can greatly limit your future ability to gain approval for broader indications.

- Inadvertently giving your competitor the lead, because your competitor determined to narrow the indication for its technology, and thus appears to get better overall results.

- Limiting your ability to maximize price by not anchoring your value on the highest-benefiting patients

However, if you take the time to identify and understand your technology’s ideal patients, and implement strategies to motivate physicians to adopt your technology, you will know what to expect, and be better positioned to maximize your technology’s realizable market opportunity.

The bottom line is, changing standard-of-care clinical practice is very difficult. A targeted and focused patient and commercial approach is required to achieve broad adoption with the lowest investment and the greatest return in the shortest time. While most venture-backed start-ups have no intention of following this road to its end, being on any other road rarely leads where they want to go.

The case studies referenced in this article can be accessed here.

About The Author

Mike Fix is Director of Life Sciences at Navigant. He has more than 15 years of experience across the pharmaceutical and medical device industries, with additional experience in retail. His work focuses on leading engagements assessing market landscapes for startups, mid-size, and multinational medical device manufacturers. He also manages and develops the firm's market development software application. Most recently, he has worked on projects in therapeutic areas including chronic venous insufficiency (CVI), coronary artery disease, emphysema, heart failure, hospital acquired infection, migraine, and obesity.