The De Novo Classification Process: A Work in Progress

By Janice Hogan, Partner and Co-Director of the FDA/Medical Device Practice, Hogan Lovells US LLP

How Much Has The Process Improved Since FDASIA?

When Congress created the de novo classification process in the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997 (FDAMA)i, the goal was to create an intermediate pathway between a 510(k) submission and a PMA application for innovative, low-risk devices. The purpose was to foster the development and clearance of innovative products by reducing the regulatory burden.

During the first 15 years after enactment, the de novo process was used infrequently by FDA, with only 76 completed submissions from 1997 until the enactment of FDASIA in July 2012, compared to over 500 PMA applications and 40,000 traditional 510(k) notices over the same time period. In 2012, Congress enacted reforms to the de novo process as part of the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA)ii in an effort to streamline and improve this pathway. Key questions about the de novo process remain important to assessing its viability and the effectiveness of the FDASIA modifications:

- Was FDASIA effective in streamlining the de novo process and improving review times?

- Why is the process used so infrequently, and is this improving?

- Are some types of products more suitable for the de novo pathway than others?

- Is there significant variability in use of the de novo process across FDA review divisions?

- How much clinical data is required to support a de novo submission?

- Is the burden of a de novo submission significantly reduced compared to a PMA?

- Does a de novo facilitate competitors’ entry into the marketplace via the 510(k) pathway?

Post-FDASIA De Novo Review Time Is Not Significantly Improved, Remains Highly Variable

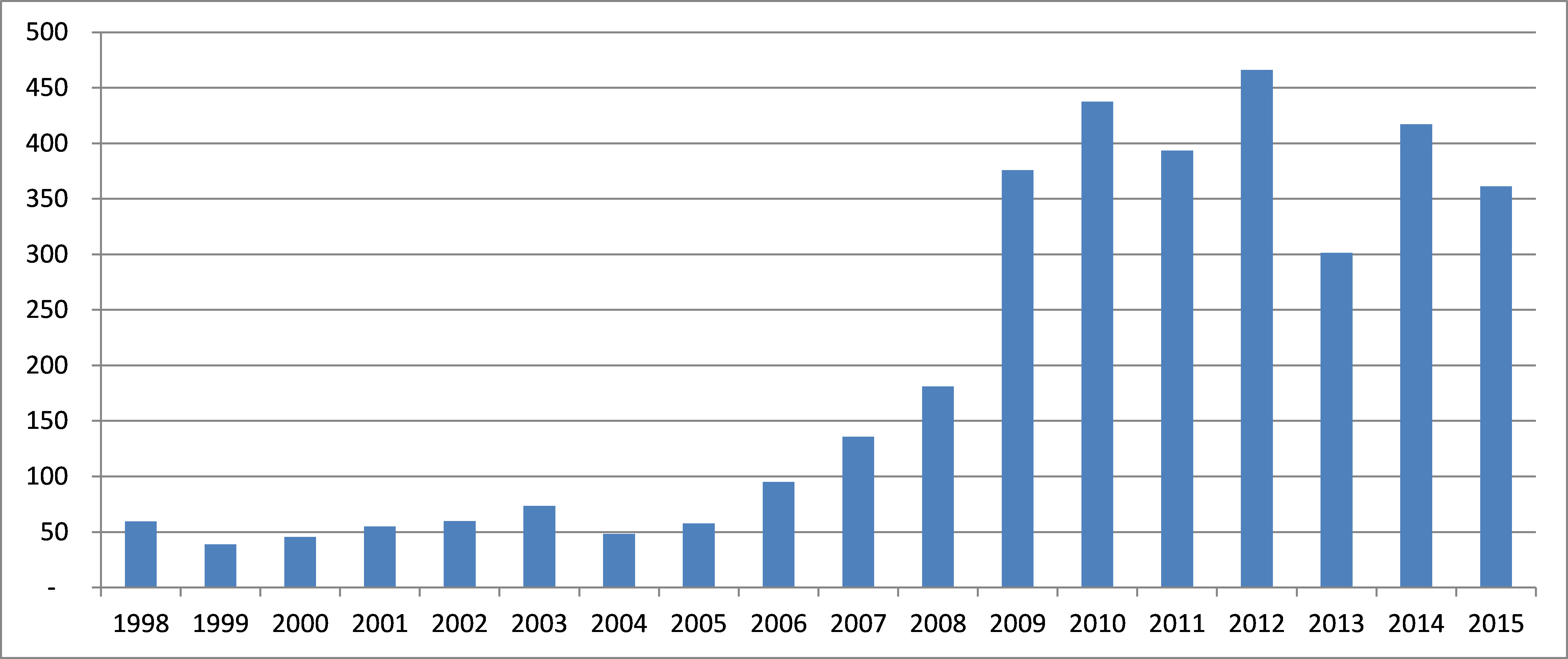

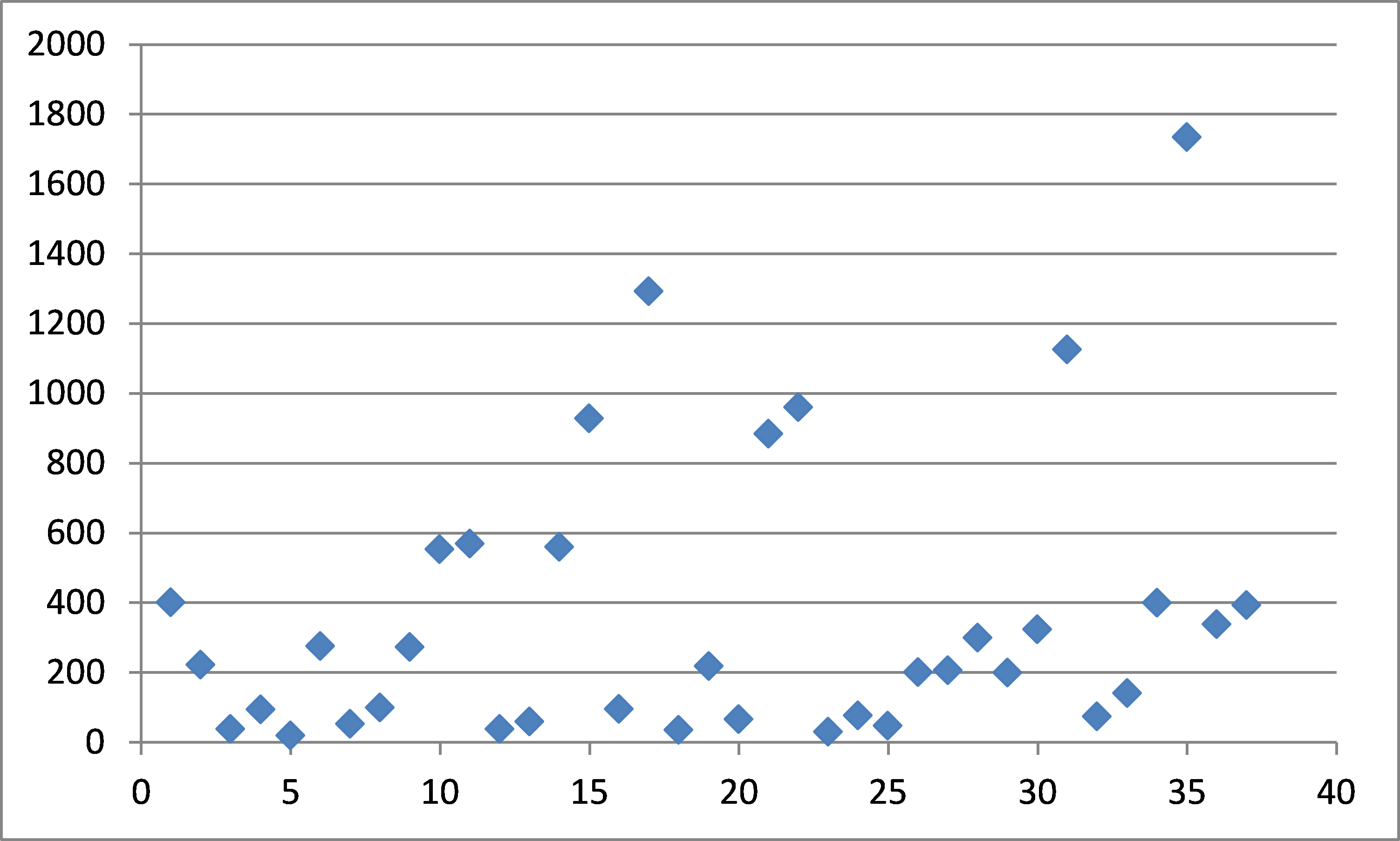

One of the key reforms to the de novo pathway implemented in FDASIA was the creation of a “direct” de novo pathway. Previously, an applicant was required to first submit a 510(k) then, in a second step, file a de novo petition after the 510(k) was found “not substantially equivalent” (NSE). This change was designed to help reduce review times. However, as shown in Figure 1, mean de novo review times show limited evidence of improvement over the past several years compared to the pre-FDASIA period.

As indicated in Figure 1, while the mean de novo review time dropped significantly between 2012 and 2013, this decrease has not persisted in 2014 and 2015 YTD. Overall, considering all the data since 2009, the mean review time for de novo submissions has consistently remained at approximately one year.

It does appear, though, that the direct de novo process offers some advantage in review time compared to the previous two-stage process. The mean de novo review time for direct de novo submissions only, all of which have been filed post-FDASIA, is 295 days (median 274 days). However, over the entire history of the de novo process since 1997, the current review times remain much higher than in the 1997-2004 period.

It should be noted that, prior to FDASIA, de novo review times did not include the time that could be spent on 510(k) review prior to a “not substantially equivalent” decision and therefore may significantly understate the total FDA review time. For example, prior to FDASIA, if an applicant submitted a 510(k) notice that was under review for two years, followed by a de novo submission that was under review for 60 days, only the 60-day review would be reflected.

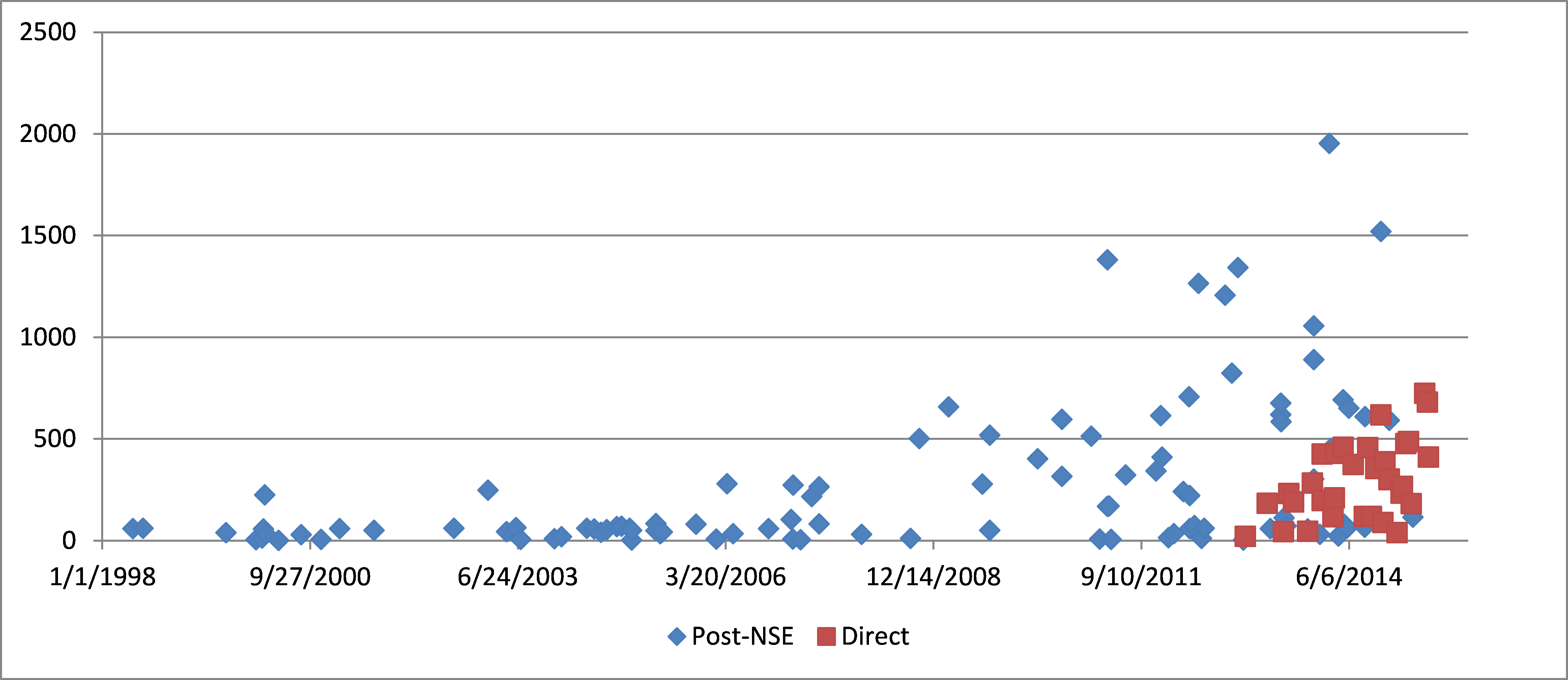

Nonetheless, variability in de novo review times remains high, as illustrated by the scatter plot In Figure 2. Direct de novo submissions since FDASIA generally show lower review times than many of the post-NSE de novo submissions prior to FDASIA, but the range of review times remains wide; several of the longest review times (> 600 days) have occurred in 2015. Thus, the availability of a direct de novo procedure has not eliminated the risk of very long review times.

This variability is likely attributable, at least in part, to the relatively infrequent use of the de novo process compared to the 510(k) and PMA mechanisms. Most divisions clear fewer than five de novo submissions per year, and many may not handle any de novo submissions for multiple years.

Use Of The De Novo Process Is Increasing

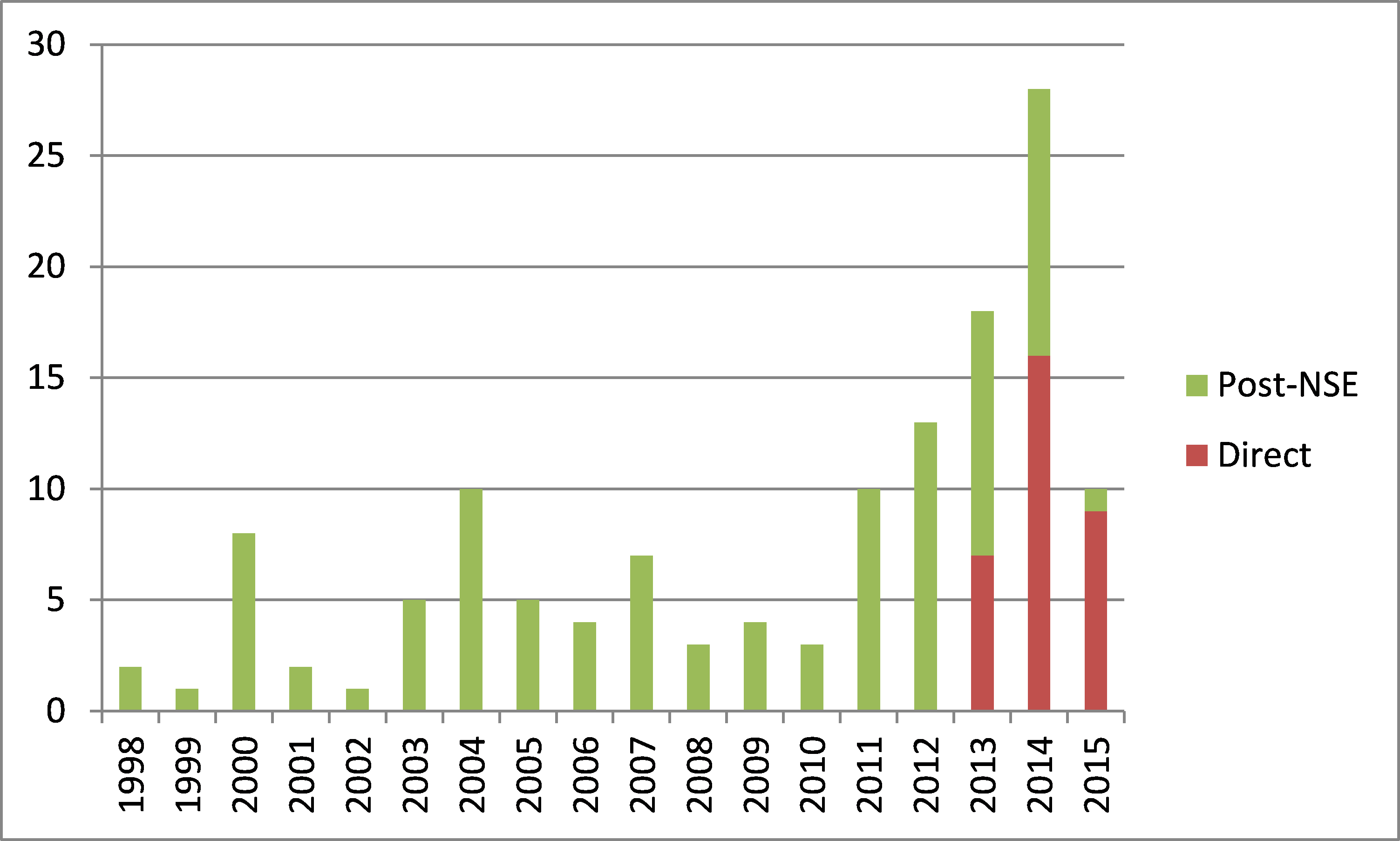

Use of the de novo process is increasing, as shown in Figure 3. Although the increase appeared to begin before enactment of FDASIA, the number of de novo clearances in 2014, a total of 28, was the highest number in any year since the process was created in 1997. Although the 2015 data to date suggests that the number of de novo clearances may be lower than in 2014, the three-year period from 2013-2015 clearly demonstrates greater use of the de novo process than the pre-FDASIA period.

Figure 3 also shows that, since FDASIA created a “direct” de novo option in 2012, this option has been used to an increasing extent. The continuing number of post-NSE decisions (rather than direct de novo decisions) in 2013 and 2014 largely reflects submissions that were already in progress prior to FDASIA. Over time, it is anticipated that nearly all de novo submissions will follow the direct pathway, as shown in the partial year 2015 data above.

Significant Variability Remains Across Review Divisions and Therapeutic Categories

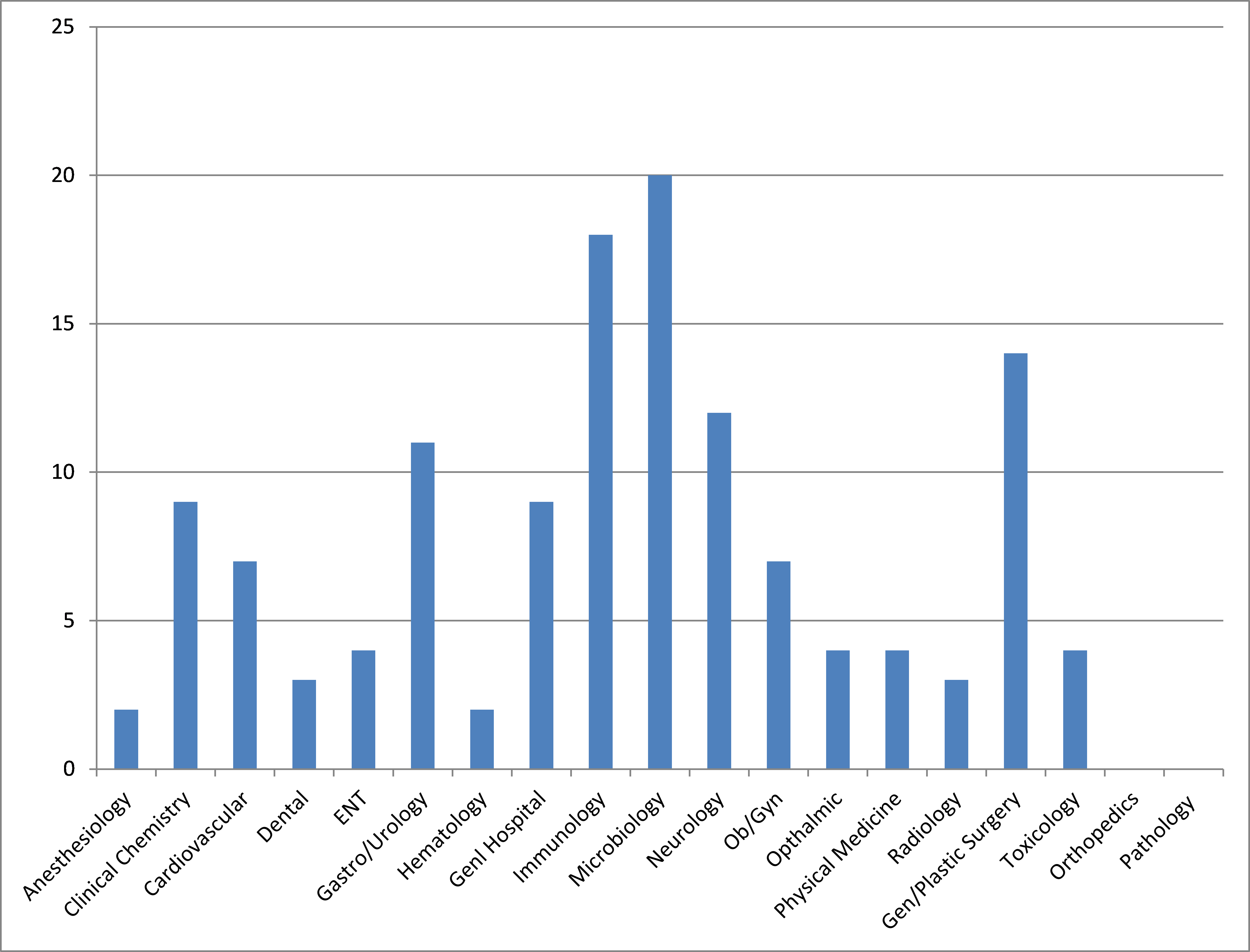

While the overall volume of de novo submissions is increasing somewhat since FDASIA, use of the process by review division remains highly variable, as illustrated in Figure 4.

As shown in Figure 4, only two product categories remain where the de novo process has never been used successfully to date: Orthopedics and pathology devices. The reasons for this are unclear. For orthopedic products, this likely relates to the minimal use of the de novo process for implanted devices.

Some implanted products have received de novo clearance in other therapeutic areas, such as cardiovascular and urology. However, implants represent a small minority of all de novo submissions. In other areas, the de novo process has been used rarely; for example, no de novo submission has received clearance in the anesthesiology category in over 15 years, with the last de novo clearance in 2000. Therefore, there appears to be somewhat inconsistent interpretation of de novo eligibility across divisions.

It is also notable that very few groups within CDRH have used the de novo process more than 10 times since its creation. These are limited to the gastroenterology/urology, immunology, microbiology, neurology, and general/plastic surgery therapeutic areas. Thus, it appears that there is still potential for greater use of the process in other therapeutic areas.

In addition, there is consistent evidence over time of shorter review times for diagnostic de novo submissions compared to therapeutic device de novo submissions. For direct de novo submissions, all of which have been filed post-FDASIA, the mean review time for diagnostic devices is approximately half that of de novo submissions for therapeutic products: 174 days compared to 350 days. In addition, over half of the direct de novo submissions for therapeutic devices required over a year of review, compared to only one diagnostic device.

The Amount Of Clinical Data Required To Support A De Novo Submission May Be Comparable To A PMA, Depending On Product Type And Level Of Risk

A frequent question regarding the de novo process is what amount of data is required to support clearance of this type of submission. The range of answers to this question is very broad and highly dependent on the type of product and the level of risk. Looking at only those de novo submissions since enactment of FDASIA in 2012, the range of data requirements is illustrated in the scatter plot in Figure 5.

It should be noted that this includes both therapeutic and diagnostic devices. For diagnostic de novo submissions, a large number of samples may often be tested to support clearance; thus, the majority of the highest numbers are from diagnostic submissions, which in some cases have required testing of 500-1000 samples or more. For most therapeutic products, the number of patients included in clinical studies has more typically been less than 200. Approximately 40 percent of the submissions were cleared based on studies of 100 patients or less.

However, even if the amount of clinical data required to support a de novo submission is not significantly reduced compared to a PMA application, the process offers other advantages that reduce regulatory burden. For example, very few de novo submissions have ever undergone advisory panel review, while first-of-a-kind PMAs may often require panel input. A de novo submission also does not require submission of detailed manufacturing information in most cases, nor is a pre-approval inspection of the company’s manufacturing facility generally necessary. A de novo submission also does not require payment of a user fee. Following clearance, de novo submissions also do not require annual reporting, nor are postmarket approval studies generally required. Device modifications following de novo clearance also are subject to the framework for assessing 510(k) device modifications, compared to the more stringent PMA supplement requirements. These differences may provide significant cost savings over the life of the product.

De Novo Clearance Often Does Not Facilitate Competitor 510(k) Clearance

In considering whether to pursue a de novo pathway, companies must evaluate both time and effort and the potential business implications of choosing this regulatory approach. If the review time and data burden for a de novo are close to those of a PMA, a PMA approach theoretically affords a higher regulatory barrier to competition. However, if a de novo pathway offers advantage in terms of reduced review time and data collection burden, then a lesser degree of competitive protection may be acceptable.

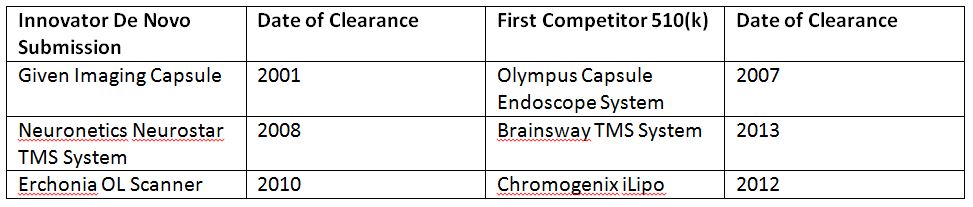

Review of the entire history of the de novo process suggests that the likelihood of a competitor following a de novo submission with a traditional 510(k) is relatively low, although legally permissible. Of the nearly 70 de novo submissions cleared since the beginning of 2012, less than a dozen have been followed by a competitor clearance in a traditional 510(k).

Although over time more of these products may be followed by 510(k) clearances for competitive products, the data generally indicates that there is at least a significant time lag — in the majority of cases — between an initial de novo clearance and the first subsequent 510(k) clearance for a competitive product. Typically, the delay between the initial de novo clearance and the first competitor 510(k) clearance has been on the order of several years, with some exceptions. Several examples are noted below.

Among the few exceptions to this rule are balloon aortic valvuloplasty devices. The initial de novo clearance in this category for the Numed PTV device in 2012 was quickly followed by multiple competitive clearances. There are also a number of diagnostic devices where an initial de novo submission was rapidly followed by one or more competitive 510(k) clearances. Overall, however, while a de novo clearance does not present as high a regulatory barrier to competition as a PMA, there is generally a significant “lead time” between the innovator’s de novo clearance and any competitive 510(k) clearances.

FDA also appears to interpret the scope of a de novo narrowly in determining whether a subsequent product can be 510(k) cleared using the de novo-cleared product as a predicate. For example, while Neuronetics obtained de novo clearance of its Neurostar transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) device for use in refractory depression, and was followed by competitive 510(k)s for this indication, subsequent applications of TMS technology to other indications (e.g., migraine) by other companies have required new de novo submissions.

Finally, where clinical data has been required to support a de novo clearance, FDA has generally required a competitor 510(k) following the initial de novo submission to include similar clinical data. For example, in the case of the TMS example above, Neuronetics was required to provide robust clinical data to support de novo clearance. The first competitor 510(k) that was cleared five years later also included a robust clinical study in over 200 patients.

Conclusions

Despite Congressional and FDA efforts to improve the de novo program, there is limited evidence of meaningful improvement in review time. While the process is being used more frequently than in the past, average review times remain at approximately one year, similar to the average review time for PMA applications. In addition, there is considerable variability in review times and in use of the de novo process across therapeutic categories. De novo submissions for diagnostic devices tend to proceed more rapidly than for therapeutic products; some types of product categories, such as orthopedic devices, have never to date been successfully cleared via a de novo submission.

The amount of data required to support a de novo submission may in some cases be reduced compared to a PMA, while in other instances the amount of data required has approached that of a PMA. There is some indication based on prior de novo clearances that the process affords more flexibility in study design compared to a PMA, with a number of de novo clearances supported by single-arm studies, rather than randomized, controlled investigations, as would typically be required for PMA approval. There are, however, other benefits of a de novo pathway compared to a PMA, particularly as related to postmarket reporting and compliance.

Recently, FDA has issued new guidance regarding the Expedited Access Pathway (EAP), which would be available for “breakthrough” products cleared via the de novo route. It is possible that this program may yield further improvement for some de novo submissions.

Overall, while the de novo program may provide a useful regulatory approach as an alternative to a PMA application for some products, the reforms implemented under FDASIA have not yet produced meaningful and consistent streamlining of the procedure. Because of the significant variability in de novo pathway usage and review times across therapeutic categories, manufacturers should carefully assess not only overall de novo statistics, but data within each therapeutic category, to assess whether it is likely to provide advantage for a specific product.

About The Author

Janice Hogan is the managing partner of Hogan Lovells' Philadelphia office and is co-director of its FDA/Medical Device practice. Janice focuses her practice primarily on the representation of medical device, pharmaceutical, and biological product manufacturers before the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

A biomedical engineer, she held positions in marketing/marketing research for a major pharmaceutical manufacturer prior to becoming an attorney. She has authored articles regarding the medical device 510(k) review process, regulation of medical software, orphan drug regulation, and medical device products liability, and a chapter of a recent textbook, Promotion of Biomedical Products (FDLI 2006).

Janice has served as an adjunct professor at the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia and as a guest lecturer at the Wharton School, Drexel University, and Stanford University on the development and regulation of medical products. She is also a frequent lecturer at FDA regulatory law symposia and conferences on topics related to premarket approval of medical products, combination products regulation, and product development. She has also served on the faculty of FDA's staff college training for new review staff.

Questions to the author may be directed to janice.hogan@hoganlovells.com.

Resources

- Public Law 105-115, January 7, 1997.

- Public Law 112–144, July 9, 2012.