The Science Of Patient Preferences In Med Device Clinical Trial Design

By Marina Damiano and Stephanie Christopher, Medical Device Innovation Consortium

The p-value.

Statisticians use it. Non-statisticians have heard of it (likely in the context of the standard threshold of p = 0.05). While it’s not the only component of a clinical trial design, the p-value helps determine the maximum acceptable level of uncertainty associated with clinical evidence and, in a way, the fate of patient access to a new medical device.

But, is the traditional 0.05 threshold too restrictive for the patient populations willing to accept more uncertainty, depriving them of treatment options? Is it too permissive for other patient populations? Can we optimize clinical trial design by considering patients’ urgency for new therapeutic options, as well as their willingness to accept uncertainty?

These questions on optimizing clinical trial design were the focus of a nearly two-year collaboration between the FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH), Parkinson’s patients (via The Michael J. Fox Foundation Patient Council), MIT, RTI Health Solutions, and the Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC) to move clinical trials from generic p-values of 0.05 to therapy-specific patient-values. (For more on p-values, read the American Statistical Association’s Statement on P-values and Statistical Significance, its first-ever position statement on statistical practice).

We will share here an overview of the process, the results, and lessons learned to provide insight for fellow MDO readers considering a similar approach.

Elevating the Science of Patient Input In Clinical Trial Design: The Process

Setting patient- and therapy-specific significance levels may be a pathway to treatment access for patients with a higher risk tolerance and no effective therapies. In these cases, the standard statistical threshold for determining therapeutic effectiveness in clinical trials may not reflect patients’ perspectives on the trade-off between the risk of approving an ineffective therapy (Type I statistical errors) and rejecting an effective therapy (Type II statistical errors). Ultimately, the motivation for this project is to optimize clinical trial design to meet patients’ needs.

We pulled in diverse stakeholders from the medical device and healthcare ecosystem to address the project in three parts:

- Identify the outcomes important to patients, family members, and caregivers — FDA reviewers participated to ensure that the study also captured concerns that reviewers believed they would need to address when evaluating a new device for PD.

- Design and conduct a patient preference assessment study based on the outcomes identified as most important to Parkinson’s Patient.

- Design methods for clinical trials based on explicit patient input. (Read more about specific project aims here)

Patients As Scientific Collaborators

This project marks the first time MDIC has partnered directly with a patient group to engage patients as research partners to give direct input on the design and execution of the project. Our patient scientists were members from The Michael J. Fox Foundation (MJFF) Patient Council, a 29-member group of Parkinson’s patients who advise the Foundation on “programmatic fronts including (but not limited to) strategies to best convey patient priorities to the research community and its funders and patient roles in developing novel ways to conduct research.”

Seven patient scientists participated in a series of six two-hour calls and in-person discussion groups to refine attributes, benefits, and risks that were “meaningful” to those living with Parkinson’s. For example, our first round of attribute selection did not include pain. But, we learned from our patient scientists that pain and its magnitude are some of the most important factors to them, and thus included it in our second round of attribute selection.

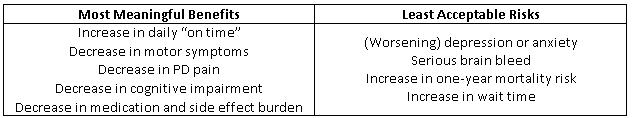

We then distributed a survey to the entire MJFF Patient Council to narrow the attributes to be used in our patient preference study. We further tested the attributes and survey through phone interviews with 20 MJFF community members who were not part of the Patient Council. This was an iterative process that helped us refine the survey to make sure it was interpreted as intended, that patients could answer the questions, and that the attributes most meaningful to the most patients were the ones included in our final version of the survey. Through this process, we arrived at what the patients felt were the most meaningful benefits and least acceptable risks a PD treatment could offer (see table below).

We then deployed the survey to more than 10,000 Parkinson’s patients via Fox Insight, MJFF’s online platform for collecting “patient-reported data about health-related experiences from volunteers with and without Parkinson's disease.” In six weeks, we received 2,752 completed surveys and began analysis to understand patients’ benefit-risk preferences for a hypothetical device to treat Parkinson’s Disease.

Using Patient Preference Information To Set Significance Levels In Clinical Trial Design

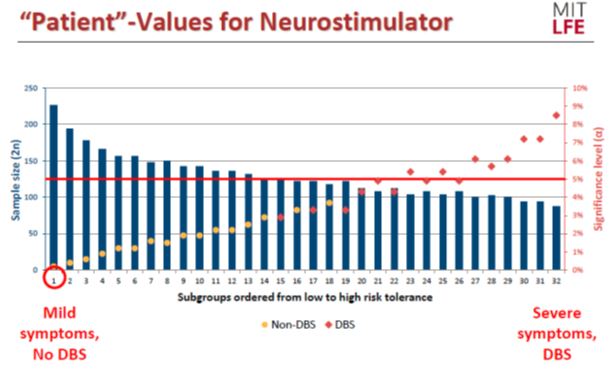

Andrew Lo and colleagues at MIT previously put forth a Bayesian Decision Analysis framework that used patient information to set p-values in a clinical trial design.1,2 Using that framework and the patient benefit-risk profile that resulted from patient preference study, we designed a two-arm, randomized clinical trial for a hypothetical neurostimulation device. Because of the large sample size, we were able to stratify patients based on their risk tolerance and model the acceptable significance level — the “patient-value” — for each subgroup based on those tolerances.

Fig. 1 shows two important sets of data. The first is the sample size as a function of patient risk tolerance (blue bars, left y-axis). As risk tolerance increases across the patient subgroups, the available sample size for each subgroup decreases. The second is the patient-centered significance level as a function of risk tolerance (red dots, right y-axis). As risk tolerance increases across the patient subgroups, the patient-centered significance level increases. The solid, horizontal red line represents the standard 5 percent significance level (p-value = 0.05).

Fig. 1 — “Patient”-values for a hypothetical neurostimulator device. Image courtesy of Shomesh Chaudhuri, MIT, May 2018 MDIC Patient-Centered Clinical Trials Workshop

The spectrum of risk tolerance in the subgroup ranged from “low” — patients with mild symptoms who have no experience with deep brain stimulation (DBS), a surgical treatment for Parkinson’s in which a device that controls movement via electrical impulses is implanted in the brain — to “high” (patients with severe symptoms, plus experience with DBS).

For patient subgroups in the lower one-third of risk tolerance, the patient-centered significance level was approximately 2 percent. For patient subgroups in the middle one-third of risk tolerance, this significance level ranged from approximately 2 percent to 5 percent. For patients in the upper one-third of risk tolerance, the optimal significance level was at or above 5 percent, with the most risk-tolerant subgroup having a maximum acceptable significance level of nearly 9 percent.

Based on these data, our key findings were:

- A fixed significance level of 5 percent does not always maximize patient value

- For risk-tolerant subpopulations (experience with DBS, severe cognitive and motor function impairment), clinical trials are overly conservative

- For patients with less severe symptoms, traditional thresholds of 5 percent may be too permissive

Though the pilot focuses on a specific disease state, Parkinson’s disease, the method may be generalizable to other diseases, and has the potential to remove barriers to therapy access by giving patients a pathway to potentially breakthrough, life-saving technologies based, in part, on their risk tolerance.

Elevating the Science of Patient Input In Clinical Trial Design: Reflections, Challenges, And Takeaways

Collaboration was crucial to the success of this project, and project collaborators weighed in with their thoughts during a May 18, 2018 workshop.

- Involve Patients With A Clear Purpose In Mind

“If you’re going to involve patients, make sure you ask concrete questions, so you can get concrete answers. Incorporate what they say or think about what they say. Don’t do it because it’s ‘in’ or ‘hot’,” said Margaret Sheehan, a patient scientist and a Partner at Ashurst LLP. Fellow patient scientist Anne Cohn Donnelly, a senior lecturer at Northwestern University, concurred, stating, “We knew we were being listened to and that was motivation enough to stay involved.”

Resist the temptation to engage patients just because other sponsors have done so. Understand how the engagement fits into the bigger picture, and have a plan to use patients’ time and input productively. We asked a lot of our patient scientists. They willingly stepped up because we listened to them, respected them, and made changes and improvements to our methods based on their input.

- Prepare For FDA Scrutiny

Owen Faris, Ph.D., Clinical Trials Director for FDA CDRH, said during the workshop’s closing panel that “We need to keep building upon the work we’ve previously accomplished. Now, we have an example tool, the next step is…let’s build upon it and use it. Let’s see an example where we can use it. It won’t be an easy conversation and those first couple of times you’ll get plenty of questions that will need some prolonged discussion to address. But that’s the next step.”

CDRH has invested significant resources in patient engagement and the science of patient input, in addition to this project. Though this project is a conceptual starting point for similar real-world submissions, it is important for sponsors to remember and prepare for the fact that, when they bring a new method or clinical trial design to FDA, reviewers will have questions, and it will take time to agree on a trial design.

- Patients Require A New Solution

“Heterogeneity matters. If you’ve met one person with Parkinson’s, then you’ve met one person with Parkinson’s,” summed up Brett Hauber, Ph.D., Senior Economist and VP of Health Preference Assessment at RTI Health Solutions.

The Parkinson’s community is diverse in many aspects. In this study, our sample came from users of Fox Insight, who do not necessarily represent all PD patients, including those without internet access or those who are not interested in volunteering their perspective. While working with patient groups is a good approach for getting a solid base of participants, the groups themselves are not necessarily representative of the patient population as a whole.

Sponsors interested in using patient preference information to inform the development of a clinical trial for FDA should work to ensure, from the beginning, that the sample is diverse and representative of the general patient population.

“People fix [themselves] on p-values because they know the concept, but the fact is, in order for us to replace p-values with something more useful, we need to provide it,” said Andrew Lo, Ph.D., a professor at MIT Sloan School of Management.

Significant work remains to shift clinical trial culture from one-size-fits-all to a more tailored approach that optimizes clinical trial design and product development. As we develop the science around this and other tailored approaches, it’s always a good idea to talk to the FDA about your product and approach using the pre-submission process.

In sharing our work on this project, we hope to encourage sponsors to submit similar projects to FDA and engaging the agency for early and frequent feedback so that, as a community, we have more data and examples to demonstrate to all stakeholders that this approach is worthwhile.

About The Authors

Stephanie Christopher is the Program Director for the Science of Patient Input project at the Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC).

Marina Damiano is a scientific communications consultant for MDIC and owner of Damiano Group Scientific Communications.

References

- Chaudhuri SE, Ho MP, Irony T, Sheldon M, Lo AW. Patient-centered clinical trials. Drug Discov Today. 2018;23(2):395-401.

- Montazerhodjat V, Chaudhuri SE, Sargent DJ, Lo AW. Use of Bayesian Decision Analysis to Minimize Harm in Patient-Centered Randomized Clinical Trials in Oncology. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(9):e170123.