Trends In FDA Quality System Inspections: 3 Takeaways To Ensure Future Success

By Adam Atherton, PE, RAC, independent consultant

The FDA conducts thousands of quality system inspections each year. The FDA performs inspections of medical device quality systems for products planned for or already on the U.S. commercial marketplace and publishes summaries of the inspection observations here. In this article, I present background and high-level observations on the inspection data over time. My next article will analyze FY2020 data and how it compares to previous years.

FDA inspections of medical device quality systems are driven by either the older, but still relevant, quality system inspection technique (QSIT) or the more recently developed medical device single audit program (MDSAP) model. It is unknown if these different audit approaches result in different outcomes, but it is unlikely. I expect the MDSAP methodology identifies quality system gaps quicker due to the more rigorous and systematic approach, though.

Should the auditor identify quality system deficiencies during the inspection, an FDA Form 483 will be completed detailing the concerns. The Form 483 documents the regulatory clause(s) that is violated for the audited project and is informally provided to the team involved in the inspection before the auditor leaves the facility. The formal Form 483 is subsequently sent to the company CEO, and initial responses are expected within 15 days of receipt.

Although medical device quality systems are largely subject to the 21 CFR 820 Quality System Regulation subparts, the following regulations may also apply:

- 21 CFR 803 Medical Device Reporting (five subparts) requires medical device manufacturers to track and record adverse events for legally marketed devices. Auditors will look for appropriate handling and escalation of complaints or results from post-market surveillance.

- 21 CFR 806 Corrections and Removals (two subparts) requires manufacturers to report to FDA if a medical device correction or removal was initiated due to a risk to health. Auditors will look for the completeness and urgency of field actions.

- 21 CFR 807 Registration (five subparts) requires establishments that are involved in the production and distribution of medical devices intended for commercial distribution in the United States to register annually with the FDA and to list the devices and the activities performed on those devices at that establishment. Auditors will look for any changes in the manufacturing facilities or new lines.

- 21 CFR 812 Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) (six subparts) levies requirements on manufacturers for the conduct of significant risk clinical studies, including the need for design controls. Auditors will look for documentation of device performance during the clinical trials.

Title 21 CFR 820 is composed of the following 15 subparts:

A - 21 CFR 820.1/3/5 General Provisions

B - 21 CFR 820.20/22/25 Quality System Requirements

C - 21 CFR 820.30 Design Controls

D - 21 CFR 820.40 Document Controls

E - 21 CFR 820.50 Purchasing Controls

F - 21 CFR 820.60/65 Identification and Traceability

G - 21 CFR 820.70/72/75 Production and Process Controls

H - 21 CFR 820.80/86 Acceptance Activities

I - 21 CFR 820.90 Nonconforming Product

J - 21 CFR 820.100 Corrective and Preventive Action (CAPA)

K - 21 CFR 820.120/130 Labeling and Packaging Control

L - 21 CFR 820.140/150/160/170 Handling, Storage, Distribution and Installation

M - 21 CFR 820.180/181/184/186/198 Records

N - 21 CFR 820.200 Servicing

O - 21 CFR 820.250 Statistical Techniques

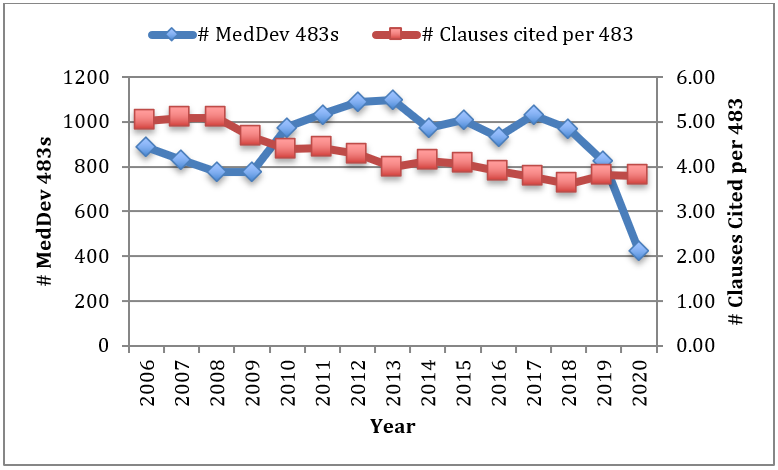

While the number of Form 483s issued annually against manufacturers has remained somewhat steady over time, the number of clauses cited per 483 has continually declined from five to four. The dip in FY20 is likely an outlier.

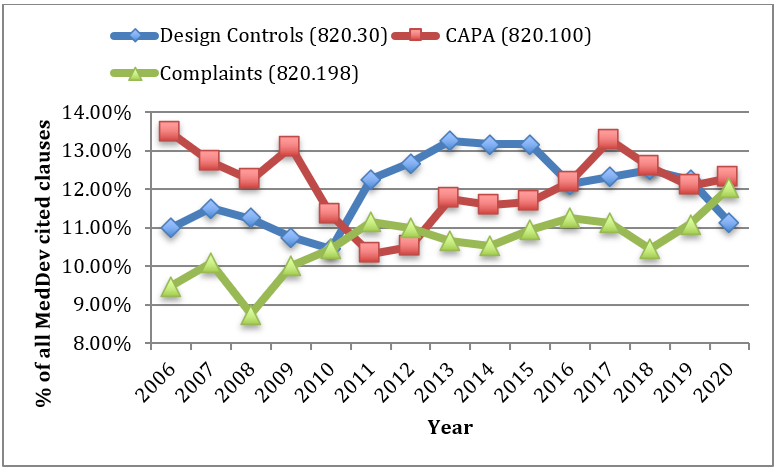

The top three cited sections are consistent across all years, other than 2008 when IDE (21 CFR 812) edged out Complaints (21 CFR 820.198). CAPA (21 CFR 820.100), Complaints (21 CFR 820.198), and Design Controls (21 CFR 820.30) typically comprise approximately 35% of all cited sections.

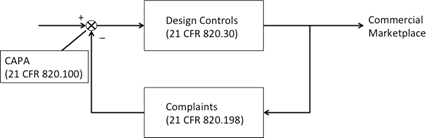

Interestingly, the three most cited sections together can be represented by a negative feedback control system. Design Controls (21 CFR 820.30) form the forward path, Complaints (21 CFR 820.198) the negative feedback, and CAPA (21 CFR 820.198) the feedback output that adjusts the reference input feeding Design Controls (21 CFR 820.30). Certainly, this is no coincidence.

What Should I Do With My Quality System?

In your medical device quality system, you can take steps now that will help ensure success in future audits, submissions, and development.

1. Document and follow your processes.

If team members take shortcuts around the documented processes, stop the practice immediately and then find out why that is happening. It is likely there is an opportunity for improving the process. If a gap in the process is identified (and, yes, you need to be looking for these), document a plan to address it on a priority basis. Like quality documents, processes can change with appropriate coordination and controls in place. A learning organization has the potential to be a high performing one.

2. Check to ensure there is clarity at the interfaces.

For example, in the negative feedback control system above, there are several interfaces where there will likely be distinct procedures, or even quality systems, and functions involved. Design Controls include Design Transfer into the production environment, which necessitates transfer of ownership from development to manufacturing and may include accounting for different geography or a contract manufacturer. Are the procedures clear? Are quality agreements comprehensive? Are the different and transitioning responsibilities detailed and agreed to?

The interface between the marketplace and complaint handling is post-market surveillance. Recent changes to the EU medical device regulation (MDR) and ISO 14971 include post-market surveillance rigor. Post-market surveillance must be reactive, proactive, and strategic because the medical device manufacturer of record owns the device’s performance and reliability. Are procedures in place to update the risk management file? Is there a fast path in complaint handling in case an adverse event occurs? Is there a consistent method for capturing, handling, escalating, and closing complaints?

The integration of significant changes to an approved product may necessitate another round of design controls and subsequent regulatory activities (this does not refer to minor changes within manufacturing). These changes will hit the CAPA, project management, risk management, management, and development processes. Are CAPA obligations being met? Are planning and investigations adequately documented? Have the impacts to the design been characterized and analyzed to ensure no collateral damage is occurring with the changes? Have scope and priority been agreed to within the organization (communication gaps are common)?

3. Put on your auditor hat.

FDA auditors will generally follow either a QSIT or MDSAP process. Both of these are linked above and include questions auditors will ask. When auditors ask questions, they don’t want spin, they want documented evidence showing compliance and completeness. Challenge your internal auditors to integrate the QSIT or MDSAP methodology into their approach so the organization is better prepared for the actual audit. Is your DHF organized well? Are all your document repositories compliant with your document control procedures (21 CFR 820.40)? Do all quality documents have the appropriate approvals? Are approved priority vendors periodically audited and issues resolved?

Remember, inspections are done at a point in time against only one of perhaps many projects. To do well in an inspection is a thrill, but it does not mean there is not room for improvement. To do poorly is a disappointment and a potential impact to the customer and business, but it also tends to focus the organization on areas where immediate improvement is needed. Maintain your quality system as you learn from experience, updated regulations, regulatory or internal inspections, and problems for best results.

About The Author:

Adam Atherton, PE, RAC, is an independent consultant to medical device and combination product manufacturers. He develops strategies to address technical feasibility, new product development, remediation, regulatory, clinical, manufacturing, and post-market surveillance for Fortune 200 medical device and pharmaceutical companies as well as startup ventures. He manages key aspects of design control, risk management, product architecture, and quality systems. He graduated from Naval Postgraduate School with his MSEE degree and from California State University, Fresno with his BSEE degree. He can be reached at www.keb-llc.com or info@keb-llc.com.

Adam Atherton, PE, RAC, is an independent consultant to medical device and combination product manufacturers. He develops strategies to address technical feasibility, new product development, remediation, regulatory, clinical, manufacturing, and post-market surveillance for Fortune 200 medical device and pharmaceutical companies as well as startup ventures. He manages key aspects of design control, risk management, product architecture, and quality systems. He graduated from Naval Postgraduate School with his MSEE degree and from California State University, Fresno with his BSEE degree. He can be reached at www.keb-llc.com or info@keb-llc.com.