'Trojan Horse' Technique Proves Effective For Fighting Cancer

By Chuck Seegert, Ph.D.

Researchers from Cambridge University have employed a “Trojan Horse” strategy to attacking brain tumors by using gold nanoparticles to smuggle chemotherapy drugs inside cancer cells.

Glioblastoma multiforme is one of the most aggressive and most common forms of brain tumors seen in adults. Historically, glioblastoma has been incredibly resistant to treatment, partly because it intertwines closely with healthy tissue, making surgical removal nearly impossible. Statistically, patients diagnosed with the condition have only a 6 percent survival rate after 5 years.

Traditionally, chemotherapy has been used to treat glioblastoma cancers, and while it may cause a decrease in the spreading of the tumor, it is often temporary. Generally, not all cells are killed, and the ones that remain are often the strongest. So when the tumor returns, it becomes resistant to the treatment.

"We need to be able to hit the cancer cells directly with more than one treatment at the same time," Dr. Watts, a clinician scientist and honorary consultant neurosurgeon at Cambridge University’s Department of Clinical Neurosciences, said in a recent press release. "This is important because some cancer cells are more resistant to one type of treatment than another. Nanotechnology provides the opportunity to give the cancer cells this 'double whammy' and open up new treatment options in the future."

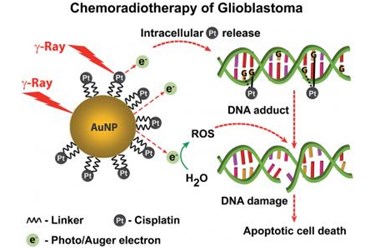

The combined therapy consists of gold nanoparticles coated with polyethylenimine, a polymer that interacts with proteins on the cellular surface, and cisplatin, a common chemotherapy drug. When the nanoparticles are ingested by the cancer cell, they release the cisplatin which has toxic effects.

Once inside the cell, the nanoparticles are exposed to radiation therapy, which causes the gold to emit low energy electrons called auger electrons. Auger electrons damage the cell’s DNA, leading to cell death. The beauty of the technique is that the electrons have energy levels that are so low that they potentially won’t damage the surrounding cells.

In a study published in the journal Nanoscale, the treatment method was tested in cells cultured from glioblastoma patients. Gold by itself was shown to be damaging to the cancer cells, but eventually they recovered. Gold and chemotherapy together, however, led to a reduction in the cancer cell population that was 100 thousand times more effective than the untreated cells. What’s more, the cell culture did not appear to be renewing, or growing back.

The project was a collaboration between researchers and clinicians, which ensured its clinical relevance.

"It made a huge difference, as by working with surgeons we were able to ensure that the nanoscience was clinically relevant," said Mark Welland, professor of nanotechnology and a fellow of St. John's College, University of Cambridge, in the press release. "That optimises our chances of taking this beyond the lab stage, and actually having a clinical impact."

Nanoparticles are currently a focus of intense research in the field of cancer medicine with researchers using them to selectively heat cancer cells, improve diagnostics for tumors, and even reduce tumor progression in multiple myeloma.

Image Credit: M. Welland