FDA Vs. Congress: The Software Showdown

By John Giantsidis, president, CyberActa, Inc.

September 2022 will be remembered as a seminal turning point in digital health in the U.S. It was not FDA’s concluding its Software Precertification Pilot program, where the FDA finally admitted and further validated our cGMPs for SaMD approach1 that a new legislative authority is necessary to review, approve, and regulate SaMDs.2 It was not the U.S. Government Accountability Office publishing a report identifying the challenges limiting development and adoption of machine learning (ML) in diagnostics and urging the FDA and other regulators to promote collaboration to support the design of these technologies and the development of applicable standards.3

No, the seminal turning point would be issuance of FDA’s final guidance on Clinical Decision Support (CDS) software, in which the FDA disregards a Congressional directive when it enacted the 21st Century Cures Act in 2016.

Cures Act Refresher

Prior to the Cures Act, the FDA categorized software intended for medical diagnosis or treatment, including CDS software, as meeting the definition of a medical device. The Cures Act changed many aspects of FDA’s medical device regulation. Under the Cures Act, the following functions or uses, subject to certain conditions, were not to be treated as medical devices or subject to FDA oversight:

- Administrative Support: administrative support of a healthcare facility, including the processing and maintenance of financial records, claims, billing information, information about patient populations, business analytics, practice and inventory management, analysis of historical claims data to predict future utilization or cost-effectiveness, and population health management

- Healthy Lifestyle/Wellness: maintaining or encouraging a healthy lifestyle, provided the function is unrelated to the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, prevention, or treatment of a disease or condition

- Electronic Patient Records: use as electronic patient records, including patient-provided information, to the extent that the records are intended to transfer, store, convert formats, or display the equivalent of a paper medical chart so long as the records were created, stored, transferred, or reviewed by healthcare professionals or individuals working under their supervision and are not intended to interpret or analyze patient records, including medical image data, for the purpose of the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, prevention, or treatment of a disease or condition

- Transfer/Storage of Medical Device Data: transferring, storing, converting formats, or displaying clinical laboratory test or other device data and results, findings by a healthcare professional with respect to such data and results, general information about the findings, and general background information about the test or other device, unless the function is intended to interpret or analyze clinical laboratory tests or other device data, results, and findings, and

- CDS Software, if such function is:

- not intended to acquire, process, or analyze a medical image or a signal from an in vitro diagnostic device or a pattern or signal from a signal acquisition system;

- intended for displaying, analyzing, or printing medical information about a patient or other medical information (such as clinical studies and clinical practice guidelines);

- intended for supporting or providing recommendations to a healthcare professional (HCP) about prevention, diagnosis, or treatment of a disease or condition; and

- intended for enabling such HCP to independently review the basis for such recommendations that such software presents so that it is not the intent that such HCP rely primarily on any of such recommendations to make a clinical diagnosis or treatment decision regarding an individual patient.

Why Is CDS Important?

Before diving into the details of the latest CDS guidance, it is important to understand why it is so important to intentional medical device manufacturers and other organizations that did not intend to be regulated by the FDA. Under the Cures Act, numerous companies brought software to the market or have invested in software in development that were designed according to clear-cut parameters. Per the latest CDS guidance, FDA plans to oversee software that Congress explicitly removed from the agency’s oversight. This would be a quite a shock to software developers and digital health providers that were assured a new way of doing business by the Cures Act. Let’s dive into the specifics, and what software developers would have to consider if they wish to enter the digital health ecosystem in the U.S.

Data Origin

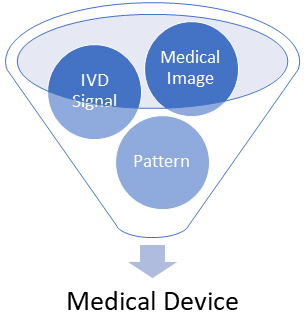

Your software would be treated as a medical device (under both the Cures Act and the CDS guidance) if its data origin is a medical image or a signal from an IVD or a pattern/signal from a signal acquisition system. The FDA established that the term “medical image” would include those images generated by medical imaging systems to view body parts, images acquired for a medical purpose, and images that were not originally acquired for a medical purpose but that are being processed or analyzed for a medical purpose. Software developers and medical device manufacturers should pay very close attention to the definition of “pattern,” which the FDA defines as the “multiple, sequential, or repeated measurements of a signal or from a signal acquisition system.” Under the latest FDA guidance, software that assesses or interprets the clinical implications or clinical relevance of a signal, pattern, or medical image would be deemed a medical device because it would “acquire, process, or analyze.”

Figure 1. FDA CDS Guidance – Data Origin

Medical Information

Software developers and designers should pay special attention to FDA’s latest interpretation of “medical information about a patient” and “other medical information,” shared in the CDS guidance. FDA considers “medical information about a patient” to mean patient-specific information that “normally is, and generally can be, communicated between HCPs in a clinical conversation or between HCPs and patients in the context of a clinical decision, meaning that the relevance of the information to the clinical decision being made is well understood and accepted.” FDA interprets “other medical information” to include information such as “peer-reviewed clinical studies, clinical practice guidelines, and information that is similarly independently verified and validated as accurate, reliable, not omitting material information, and supported by evidence.” As you can see, the latest guidance conveys FDA’s expectation to broaden the medical information definition and to render the underlying software a medical device.

Alarms And Risk Scores

FDA’s latest guidance renders software that provides a risk score or risk probability as a medical device, irrespective of the circumstances. The FDA would not consider software a medical device if it:

- provides condition-, disease- and/or patient-specific information and options to an HCP to enhance, inform, and/or influence a healthcare decision,

- does not provide a specific preventive, diagnostic, or treatment output or directive,

- is not intended to support time-critical decision-making, and

- is not intended to replace or direct the HCP’s judgment.

However, in reality, FDA is making the decisions for HCPs. Based on FDA’s latest guidance, “automation bias” — the propensity of humans to over-rely on a suggestion from an automated system — can cause errors, especially when the software provides the user with a single output, as opposed to a list of options with additional information. Urgent decision-making may not allow an HCP time to independently review the basis for the recommendations presented by the software and, as such, the FDA would bundle that under an automation bias. Some illustrative examples of software that would now be considered medical devices and subject to FDA oversight are:

- time-critical alarms intended to trigger potential clinical intervention to assure patient safety or provide a treatment plan for a specific patient’s disease or condition, and

- information that a specific patient “may exhibit signs” of a disease or condition.

Independent Review

The fourth prong of the Cures Act is for HCPs to independently review the basis of the recommendations made by the CDS, and the latest FDA view is that software developers would have to:

- include the purpose or intended use of the product, including the intended HCP user and patient population;

- identify the required medical inputs with plain language instructions on how the inputs should be obtained, their relevance, and data quality requirements;

- provide a plain language description of the underlying algorithm development and validation that forms the basis for CDS implementation, which would include a summary of the logic or methods used, the underlying data relied upon, and the results from clinical studies used to validate the algorithm/recommendations; and

- provide, in the software output, patient-specific information and other knowns/unknowns, such as corrupted or missing data, to enable the HCP to independently review the basis for the recommendations and apply their own judgment.

It is rather evident that FDA expects software developers to reveal and share detailed information about their proprietary process of developing, training, and using their algorithms.

The Bottom Line: What Does This Latest (Final) FDA Guidance Mean To You?

First and foremost, software developers currently marketing CDS that wish to follow FDA’s guidance will need to make substantial updates to the information shared by the software and associated labeling or follow a regulatory strategy entailing a premarket submission process that would afford trade secret and intellectual property protection.

Second, FDA’s latest guidance eliminated the patient/caregiver option that previously existed, also known as patient decision support (PDS). As such, any PDS in development or in the market would have to be evaluated under the traditional FDA frameworks.

Third, although the FDA purports to simply clarify its regulatory approach, the wide departure from the Cures Act and the lack of a prior opportunity for industry and stakeholders to voice their thoughts may bring some Congressional action. However, until that happens, developers of software tools for healthcare purposes should reevaluate whether their software’s functions qualify as non-device CDS under this framework and document those analyses and consider whether those functions require SaMD submission. Also, since the FDA did not confirm whether enforcement discretion would apply to the rest of a software-based CDS, it would be advisable to engage with the FDA to eliminate any regulatory surprises.

Lastly, although the FDA has deemed the latest CDS guidance as final, you can still submit comments to docket FDA-2017-D-6569, available at https://www.regulations.gov/docket/FDA-2017-D-6569.

References

- https://www.meddeviceonline.com/doc/cgmps-for-samds-0001

- The Software Precertification (Pre-Cert) Pilot Program: Tailored Total Product Lifecycle Approaches and Key Findings, https://www.fda.gov/media/161815/download

- Artificial Intelligence in Health Care: Benefits and Challenges of Machine Learning Technologies for Medical Diagnostics, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-22-104629

About The Author:

John Giantsidis is the president of CyberActa, Inc, a boutique consultancy empowering medical device, digital health, and pharmaceutical companies in their cybersecurity, privacy, data integrity, risk, regulatory compliance, and commercialization endeavors. He is the vice chair of the Florida Bar’s Committee on Technology and a Cyber Aux with the U.S. Marine Corps. He holds a Bachelor of Science degree from Clark University, a Juris Doctor from the University of New Hampshire, and a Master of Engineering in cybersecurity policy and compliance from The George Washington University. He can be reached at john.giantsidis@cyberacta.com.

John Giantsidis is the president of CyberActa, Inc, a boutique consultancy empowering medical device, digital health, and pharmaceutical companies in their cybersecurity, privacy, data integrity, risk, regulatory compliance, and commercialization endeavors. He is the vice chair of the Florida Bar’s Committee on Technology and a Cyber Aux with the U.S. Marine Corps. He holds a Bachelor of Science degree from Clark University, a Juris Doctor from the University of New Hampshire, and a Master of Engineering in cybersecurity policy and compliance from The George Washington University. He can be reached at john.giantsidis@cyberacta.com.