Risk-Based Postmarket Surveillance In The Age Of EU MDR: Incident Investigation

By Jayet Moon, author of the book Foundations of Quality Risk Management

As the central focus of the EU’s Medical Device Regulations (MDR), postmarket surveillance (PMS) and its related processes and subsystems have been in the limelight since 2017. This four-part series, using a fresh perspective, takes a bottom-up approach to PMS and starts by elaborating on the state of the art on the incident investigations in Part 1. “Investigations” are the basic iota of the PMS system upon which all further analysis, synthesis, and decision-making is based. With clarity on this most fundamental unit of PMS, a systems approach to both EU MDR and PMS will be explored in Part 2. Successful implementation of an effective EU MDR-compliant PMS requires a systems approach which requires appreciation of not only the organizational context within which PMS operates but also the knowledge management as it relates to PMS generated data, information, knowledge, and wisdom. Part 3 will focus on the bedrock of EU MDR: the risk management system. It not only explores the interfaces between risk management and PMS but also discusses the postmarket aspects of risk surveillance and their accomplishments. Part 4 will detail an important upcoming topic with relevance going beyond EU MDR. Risk-based incident trending for postmarket signal detection is quickly becoming an expectation from most regulatory agencies and EU MDR is one of the first regulations to expressly document this requirement. The regulation asks for a methodology to gauge “statistically significant increases” in a certain subset of postmarket incidents. This article details salient features of any such method such that any chosen tool can act as a postmarket risk monitor and, if used right, can also convert the lagging indicator of complaints and incidents into a leading key risk indicator. Key risk indicators can help establish preemptive preventive actions before benefit-risk profile can be adversely impacted.

processes and subsystems have been in the limelight since 2017. This four-part series, using a fresh perspective, takes a bottom-up approach to PMS and starts by elaborating on the state of the art on the incident investigations in Part 1. “Investigations” are the basic iota of the PMS system upon which all further analysis, synthesis, and decision-making is based. With clarity on this most fundamental unit of PMS, a systems approach to both EU MDR and PMS will be explored in Part 2. Successful implementation of an effective EU MDR-compliant PMS requires a systems approach which requires appreciation of not only the organizational context within which PMS operates but also the knowledge management as it relates to PMS generated data, information, knowledge, and wisdom. Part 3 will focus on the bedrock of EU MDR: the risk management system. It not only explores the interfaces between risk management and PMS but also discusses the postmarket aspects of risk surveillance and their accomplishments. Part 4 will detail an important upcoming topic with relevance going beyond EU MDR. Risk-based incident trending for postmarket signal detection is quickly becoming an expectation from most regulatory agencies and EU MDR is one of the first regulations to expressly document this requirement. The regulation asks for a methodology to gauge “statistically significant increases” in a certain subset of postmarket incidents. This article details salient features of any such method such that any chosen tool can act as a postmarket risk monitor and, if used right, can also convert the lagging indicator of complaints and incidents into a leading key risk indicator. Key risk indicators can help establish preemptive preventive actions before benefit-risk profile can be adversely impacted.

The genesis of EU MDR can be traced to lack of postmarket surveillance in the EU, which led to certain events compromising the safety of some EU citizens. In that vein, it’s no surprise that EU MDR makes PMS its central focus. In fact, Chapter VIII, Section 1, Article 83 of the regulation defines PMS with the express intent to prevent issues in the past: lack of continual monitoring after approval, lack of diversity of sources of monitoring, and lack of focus on benefit-risk:

- For each device, manufacturers shall plan, establish, document, implement, maintain and update a post-market surveillance system in a manner that is proportionate to the risk class and appropriate for the type of device. That system shall be an integral part of the manufacturer's quality management system referred to in Article 10(9).

- The post-market surveillance system shall be suited to actively and systematically gathering, recording and analysing relevant data on the quality, performance and safety of a device throughout its entire lifetime, and to drawing the necessary conclusions and to determining, implementing and monitoring any preventive and corrective actions.

The recently released guidance for PMS for manufacturers, TIR 20416:2020, defined the purpose of the PMS process as:

- Monitoring medical device safety and performance

- Meeting regulatory requirements

- Contributing to lifecycle management.

In that vein, for PMS, the EU MDR regulation wants a manufacturer to:

- Actively and systematically gather data

- Record and analyze relevant data

- Focus on quality, safety, and performance

- Engage in PMS data gathering and, more importantly, analysis as a lifecycle activity

- Use this data to draw conclusions regarding quality, safety, and performance

- Modulate rigor of PMS activities based on risk class.

And if there were any doubts regarding what exactly needed to be done with the gathered PMS data, Chapter VII, Section 1, Article 83 of the regulation also gives you a list of things to do as shown below.

(a) to update the benefit-risk determination and to improve the risk management as referred to in Chapter I of Annex I;

(b) to update the design and manufacturing information, the instructions for use and the labelling;

(c) to update the clinical evaluation;

(d) to update the summary of safety and clinical performance referred to in Article 32;

(e) for the identification of needs for preventive, corrective or field safety corrective action;

(f) for the identification of options to improve the usability, performance and safety of the device;

(g) when relevant, to contribute to the post-market surveillance of other devices; and

(h) to detect and report trends in accordance with Article 88.

In all this talk of processes, systems, and analysis, the undoing of many companies will be failure to focus on the fundamental unit of PMS.

The Incident Investigation

It is important to recognize that postmarket incident investigations may stem from both proactive and reactive data collection methods. Per TIR 20416:2020, proactive methods include:

- Surveys or questionnaires

- Physician or healthcare professional (device user) interviews

- Literature reviews

- Use of medical device registries

- Postmarket clinical follow up studies

- Public information released by regulatory agencies regarding recalls, field actions, alerts, etc.

Reactive methods include:

- Complaints

- Service reports

- Maintenance reports

- Unsolicited observations from any stakeholders

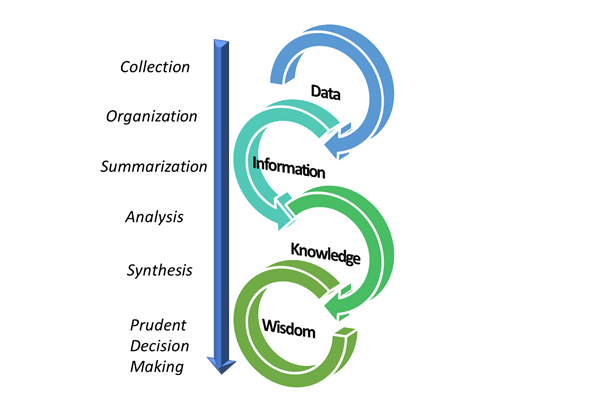

I bring this up because many companies are busy drawing up fancy templates and hiring statisticians. That’s great, but to gain true knowledge and wisdom from these activities, one must ensure that the data and information (see Figure 1 below) in the complaint and other PMS records (incident investigations) are complete, valid, and integral.

Figure 1: Data, Information, Knowledge, Wisdom hierarchy (DIKW).

Russell Ackoff, the famous systems theorist from The University of Pennsylvania, created the original DIKW model, and I’ve expanded it as Figure 1 above. Per this model, DIKW are defined as:

- Data is raw and can exist in any form, usable or not. From a systems standpoint, one data point has no meaning unto itself until its connection are explored using relevant information. It can be a fact or a signal, which are unorganized and unprocessed and hence have no or limited meaning unless contextually explored.

- Information is data that has been given meaning by situating it in relational context. It can be the What?, Who?, When?, Where?, etc. Information takes the data, adds contextual richness to it, and makes it useful for decision-making.

- Knowledge is collection and synthesis of information that is useful. It is the How?. It is information combined with understanding and capability.

- Wisdom is the evaluated understanding that rests on conversion of data to information and information to knowledge. It is the true synthesis of data, information, and knowledge to make best informed, forward-thinking judgments and decisions.

In EU MDR context, we need to talk more about the richness of incident investigations. This is the building block on which everything else is based. The wisdom we need through PMS activities is the state of device benefit-risk. To gain this wisdom, the knowledge of how post market issues occur is critical. These may include gathering data and information on:

- Did the device fail to meet specifications?

- How did the device fail to meet specifications?

- What is the relationship of the device to the incident or adverse event?

- Why did the device fail to meet specifications?

- What is the sequence of events between the alleged device failure and the alleged adverse event, if any?

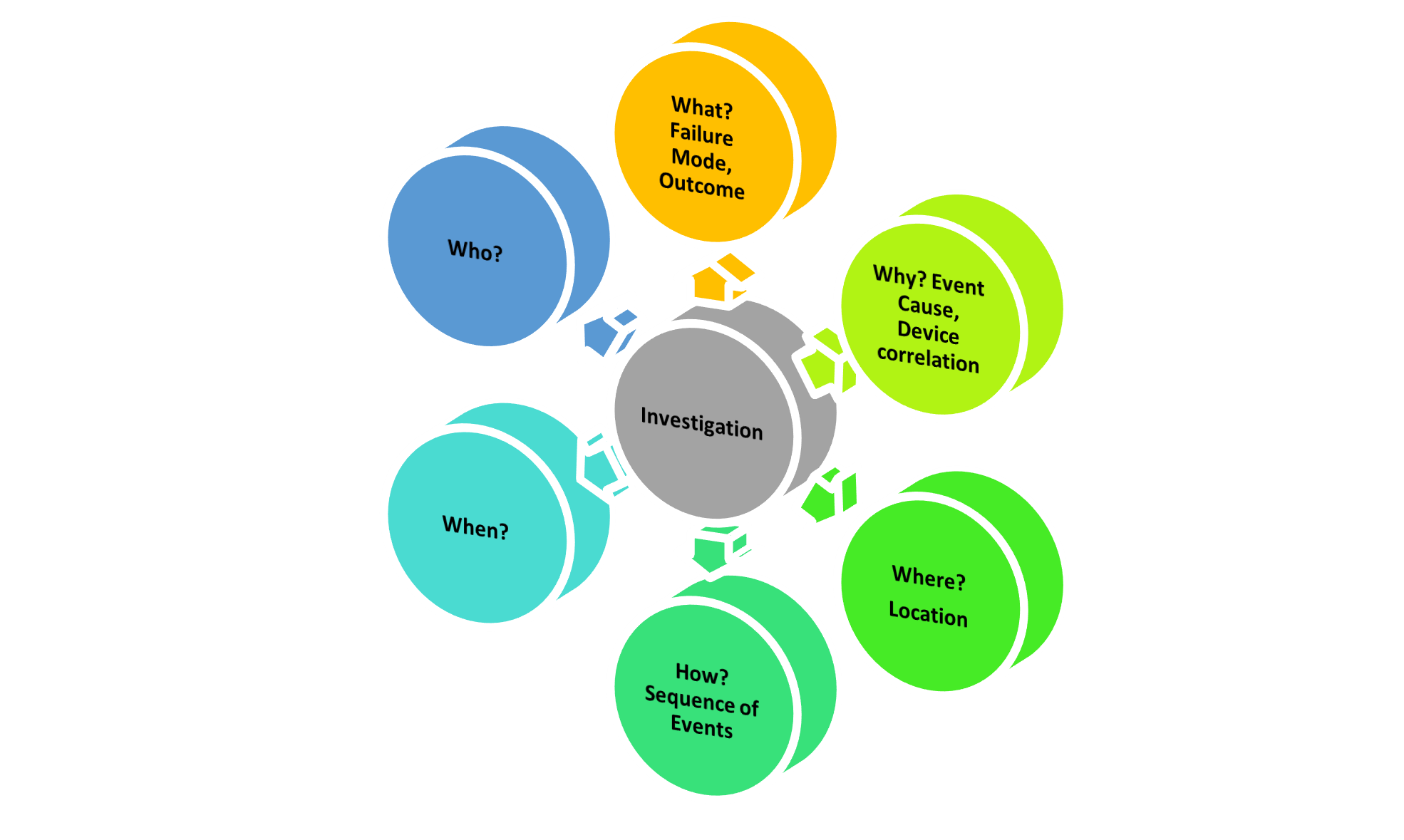

Figure 2: Elements of a complaint investigation.

The knowledge, in turn, can only be obtained if information about the event is complete and correct. The information includes Who?, What?, When?, and Where? as shown in Figure 2 above. This forms the basis of the investigation file. Regulatory body expectations for serious events go beyond these questions and additionally focus on:

- The hazard posed by the device

- The hazardous situation created by the device resulting from the failure mode

- The device failure cause may be different from the event cause

- The frequency of the event and associated risk levels

- A review of manufacturing and associated documentation for the batch

Upon occurrence of a serious event, the regulatory bodies expect high-level conclusions around the event, which not only include cause and consequence analysis but also risk assessments. Risk assessments may include assessment or re-assessment of the hazard, the hazardous situation, and harm. In addition, the frequency and severity of these incidents are expected to be tracked. Thus, PMS is no longer composed of simple complaint management wherein at most, the complaint data would be collected, organized, and summarized for “at-will” use by other functions. Instead, PMS now means continual and active analysis, synthesis, and decision-making on a range of organizational and EU MDR deliverables. In the very least, PMS function is expected to continually interface and exchange information with risk management function. EU MDR has ensured that this information flow is two-way.

Figure 3: From collecting data to decision-making.

Thus, the expectations from PMS in the new EU MDR paradigm are high. Decisions on benefit-risk are expected from continual synthesis of postmarket and other organizational data. Collection and organization of the data are the first steps, followed by summarization and its analysis (see Figure 3 above). Most importantly, we must recognize the value of the single-most important unit in PMS, the incident investigation. Its quality, completeness, and relevancy in being the best decision-making model will fall flat if the data feeding into those models is incomplete, inaccurate, or of poor quality in general.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the following two colleagues for input:

- Angelina Hakim, founder and CEO of Qunique, a quality and regulatory consultancy based in the European Union

- Veronica Cavendish-Stephens, vice president of quality and risk management of Auchincloss-Stephens, a global firm specializing in quality risk management solutions.

About The Author

Jayet Moon earned a master’s degree in biomedical engineering from Drexel University in Philadelphia and is a Project Management Institute (PMI)-Certified Risk Management Professional (PMI-RMP). Jayet is also a Chartered Quality Professional in the UK (CQP-MCQI). He is also an Enterprise Risk Management Certified Professional (ERMCP) and a Risk Management Society (RIMS)-Certified Risk Management Professional (RIMS-CRMP). He is a doctoral candidate at Texas Tech University in systems and engineering management. His new book, Foundations of Quality Risk Management, was recently released by ASQ Quality Press. He holds ASQ CQE, CQSP, and CQIA certifications.

Jayet Moon earned a master’s degree in biomedical engineering from Drexel University in Philadelphia and is a Project Management Institute (PMI)-Certified Risk Management Professional (PMI-RMP). Jayet is also a Chartered Quality Professional in the UK (CQP-MCQI). He is also an Enterprise Risk Management Certified Professional (ERMCP) and a Risk Management Society (RIMS)-Certified Risk Management Professional (RIMS-CRMP). He is a doctoral candidate at Texas Tech University in systems and engineering management. His new book, Foundations of Quality Risk Management, was recently released by ASQ Quality Press. He holds ASQ CQE, CQSP, and CQIA certifications.