The Top 10 Most-Cited Clauses In FDA FY2021 Medical Device Inspections

By Adam Atherton, PE, RAC, independent consultant

In my FDA FY2020 article I broke down the most cited clauses during FY2020, which ran from October 1, 2019, through September 30, 2020. This article explores into the inspection findings during FY2021 concentrating on design controls, in particular.

Continuing the trend started in pandemic-plagued FY2020, FDA conducted even fewer inspections in FY2021. Consequently, the number of 483s issued against medical device quality systems was slashed by another 50%, or 22% of the typical number of 483s issued prior to FY2020. Approximately 775 medical device 483s were issued in FY2021 compared to approximately 1,600 in FY2020 and approximately 3,100 in FY2019.

Despite another substantial reduction in the number of inspections, the top three most cited clauses remain Design Controls (820.30), CAPA (21 CFR 820.100), and Complaints (820.198) at 13.29%, 13.16%, and 11.10% of all cited clauses, respectively. All combined, these top three clauses accounted for 37% of all clauses cited in medical device 483s issued in FY2021. But what is included within each of these?

Design Controls Citations

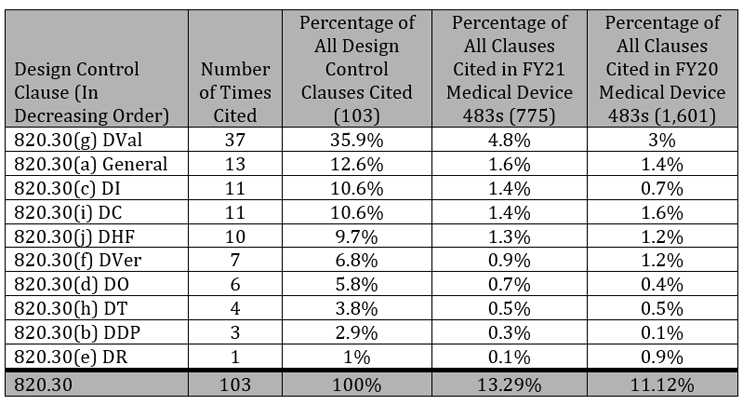

Design controls as described in 21 CFR 820.30 has 10 parts. I’ll discuss each one, ordered from the most frequent citations to least frequent.

1. Design Validation (DVal, 820.30(g)): Cited 37 times

The most frequently cited clause of Design Controls was Design Validation, which is essentially demonstrating the device conforms to the defined user needs and intended uses. Of the 103 times Design Controls was cited, DVal accounted for 37 of them, far exceeding any other Design Control clause.

Risk management is not an explicit part of design controls – it is only casually mentioned once in DVal – but it is inherent in executing all of these processes (ISO 13485:2016 does a better job in making this clear). Risk management was the most frequently mentioned part of DVal, being cited 19 times out of 37. These were split between not performing risk analysis (14) and not documenting the results of risk analysis (five).

Other Dval observations ranged from lacking or inadequate procedures (six times) to not performing or documenting the risk analysis or software validation (22 times) or not using production equivalent devices in validation studies (three times). Perhaps the most curious DVal gap, besides lacking or inadequate procedures, was design validation not confirming the device conforms to defined user needs and intended uses. This is the entire point of Dval and was cited four times.

General (820.30(a)), Design Input (820.30(c)), and Design Change (820.30(i)) were the next most cited clauses at 13 times, 11 times, and 11 times, respectively. It is important to note that Dval was cited at the approximately the same rate as these three clauses combined. For all three, the most common reason for the citation was due to lacking or inadequate procedures.

1. General (820.30(a)): Cited 13 Times

Manufacturers did not adequately establish procedures.

2. Design Inputs (DI, 820.30(c)): Cited 11 Times

Manufacturers did not adequately establish procedures or requirements were not adequately documented.

3. Design Change (DC, 820.30(i)): Cited 11 Times

Manufacturers did not adequately establish procedures.

4. Design History File (DHF, 820.30(j)): Cited 10 Times

Manufacturers did not have the documentation to show the design was developed following the approved design plan or the DHF was not established.

5. Design Verification (DVer, 820.30(f)): Cited 7 Times

Manufacturers did not adequately establish procedures or documentation and did not prove the design outputs meet the design inputs, which is fundamental to DVer.

6. Design Outputs (DO, 820.30(d)): Cited 6 Times

Manufacturers did not adequately establish procedures and did not adequately document or review DO before release.

7. Design Transfer (DT, 820.30(h)): Cited 4 Times

Manufacturers did not adequately establish procedures and did not correctly translate the design into production specifications.

8. Design and Development Planning (DDP, 820.30(b)): Cited 3 Times

Manufacturers did not document their subsequent activities sufficiently and did not update the DDP as the design evolved.

9. Design Review (DR, 820.30(e)): Cited 1 Time

Manufacturers did not adequately document the DR results in the DHF.

The breakdown of all Design Control clauses in FY2021 is shown in the following table.

CAPA Citations (820.100)

CAPA is the process of making corrections, corrective actions, or preventive actions. Of the 102 times CAPA was cited, manufacturers either didn’t document their procedures (820.100(a), cited 77 times) or they didn’t adequately capture CAPA activities (820.100(b), cited 25 times).

Complaint Citations (820.198)

Complaint is defined in 21 CFR 820.3 as “any written, electronic, or oral communication that alleges deficiencies related to the identity, quality, durability, reliability, safety, effectiveness, or performance of a device after it is released for distribution.” Complaint handling is a commercial process. There are seven separate clauses for Complaints; the first five describe the process and the last two cover the geographical location of the complaint handing unit. All of the 483s that cited Complaints were related to the process. Of the 86 times Complaints was cited, manufacturers didn’t document their procedures (820.198(a), cited 49 times), complaints of device failures were not investigated (820.198(c), cited 16 times), complaints weren’t investigated or lacked rationale for not conducting an investigation (820.198(b), cited eight times), complaint files were not maintained (820.198(a), cited seven times), records did not contain required information (820.198(e), cited four times) or complaints that were MDR reportable were not promptly investigated (820.198(d), cited twice).

Purchasing Controls, Medical Device Reporting, And Receiving Inspection Citations

After Design Controls, CAPA, and Complaints citations, the next three most frequent clause citations accounted for 19.4% of all cited clauses, which is approximately half of the top three. Purchasing Controls (820.50), Medical Device Reporting (803), and Receiving Inspection (820.80) come in at 7.1%, 7.1%, and 5.16%, respectively. Altogether, the first six clauses accounted for approximately 57% of cited clauses in FY2021.

Purchasing Controls

Purchasing Controls is the portion of the quality system which establishes the process for choosing and controlling suppliers. Of the 55 times Purchasing Controls was cited, the lack of adequate procedures accounted for 56%, or 31 times. The remaining citations were related to evaluating (820.50(a), 820.50(a)(1), cited 11 times), controlling (820.50(a)(2), cited nine times), communication (820.50(b), cited two times) and monitoring (820.50(a)(3), cited two times) suppliers.

Medical Device Reporting

Medical Device Reporting (MDR) is the clause for reporting adverse events by facilities, manufacturers, importers, and distributors. These reports are captured on the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) website.

Similar to Purchasing, the most often cited part of MDR is the lack of adequate written procedures, 31 out of 55 citations, or 75%. The remaining citations were related to delays in processing MDRs (803.17(a)(1), 803.50(1)(1), 803.50(a)(2), 803.56, cited 17 times), not investigating potential MDRs in a timely manner (803.17(a)(2), cited four times), or not providing necessary data (803.18(b)(1)(i), 803.50(b)(2), 803.52(f)(1), cited three times). MDRs by their nature necessitate an expeditious path through the quality system.

Receiving Inspection

Receiving inspection (RI) is the process used for accepting incoming components from vendors into inventory. RI citations fell into one of two buckets: the familiar lacking procedures (33 times out of 40) and improperly documenting results (820.80(b), 820.80(c), 820.80(e), cited seven times). Procedures need to cover inspections that occur during incoming inspection, in-process inspection, and final device acceptance inspections.

Rounding Out The Top 10 Clause Citations: Nonconformance, Process Validation, Management Responsibility, and Production & Process Controls

Each of these clauses was cited less than 5% of the time.

Nonconformance (NC)

NC is the process by which product that fails to meet specification is controlled separately from acceptable product. The lack of or inadequate procedures accounted for 82% (31 of 38) of the NC citations. The remaining seven times were related to not segregating NC product appropriately (820.90(a), cited six times) and not documenting rework (820.90(b)(2), cited once).

Process Validation (PVal)

PVal is necessary where the results of a process cannot be fully verified by inspection or test. PVal citations were primarily driven by not following procedures (24 times out of 35 or 69%) rather than the more typical topic of lacking or inadequate procedures (820.75(b), cited four times). The remaining citations were related to improperly documenting the results (820.75(a), 820.75(c), cited six times) or improper handling of changes (820.75(c), cited once).

Management Responsibility (MR)

The purpose of MR is to provide adequate resources for device design, manufacturing, quality assurance, distribution, installation, and servicing activities; assure the quality system is functioning properly; monitor the quality system; and make necessary adjustments. The lack of procedures for management review or the quality system in general was cited 16 times out a total of 33 citations. The remaining citations were failing to conduct or document regular management reviews (820.20(c), cited seven times), not appointing a management representative (820.20(b)(3), cited four times), not identifying a quality policy or documenting a quality plan (820.20(a), 820.20(d), cited four times), or not establishing an adequate organizational structure (820.20(b), cited twice).

Production and Process Controls (PPC)

PPC is where the regulation levies the requirement for production processes to ensure a manufactured device conforms to controlled specifications. There are many parts to this clause, including: change control, environmental controls, contamination control, and equipment installation, operation, and maintenance.

Consistent with the pattern already established here, the lack of adequate procedures tops the list at 18 times out of 32. Failing to validate production software was cited six times. Preventive maintenance was flagged four times. Inadequate monitoring and controls for production processes were cited three times. Personnel requirements were cited once. Just as design controls must be in place for design and development, so production processes must be established, monitored, and maintained to ensure continued manufacturing of compliant and consistent product.

The top 10 clauses described here accounted for 75% of all clauses cited during inspections of medical device quality systems.

4 Priority Takeaways From FDA FY 2021 Inspections

Here are summarized some key takeaways from FDA FY2021 inspections, in addition to what I presented in my previous article, Trends in FDA Quality System Inspections: 3 Takeaways to Ensure Future Success.

- Cutting across the top 10 clauses cited in FDA 2021 quality system inspections, the number one area continues to be the lack of or inadequate procedures. Of the 579 times the top 10 clauses were cited, the lack of procedures accounted for 57% of them (332 of 579). The rate of citing the lack of or inadequate procedures across all clauses is 53% (412 of 775). Not only is this the most cited area, but it may also be the easiest to address.

If you are unsure of where to start, follow these steps to add basic procedures to your quality system;

a) Open your browser and navigate to “ecfr.gov.”

b) Search for “820.30 Design Controls” or “820.98 Complaint files” or “820.100 Corrective and preventive action” or any other section in the QSR.

c) Download your controlled procedure template and transcribe these clauses into your template.

d) Tailor to your environment (this is the most challenging task).

e) Approve your procedure per your document control procedure.

f) Follow your procedure. Follow your procedure. Follow your procedure. Lather. Rinse. Repeat.

g) Update your procedure, as necessary, per document controls.

This won’t immediately produce perfect procedures, but it will provide you compliant ones that serve as a stepping stone to a comprehensive and effective quality system. You can also purchase procedures from reputable sources to expedite the process.

- All 10 clauses discussed in this paper were plagued by a lack of or inadequate procedures. However, for two clauses, Design Validation (820.30(g)) and Process Validation (820.75)), the lack of or inadequate procedures was not the primary gap. Risk analysis was the primary concern with Design Validation and poor execution or documentation was the primary concern for Process Validation. Both Design Validation and Process Validation are focused on demonstrating implemented risk controls are effective; Design Validation is focused on ensuring the use- and design-related risk controls and Process Validation is focused on ensuring the process-related controls are effective. The timing of these activities is notable as Design Validation comes just before Design Transfer and Regulatory Submission and Process Validation is done just prior to releasing manufactured product to the field.

- Accounting for approximately one third of all medical device 483 citations for 12 years running are three clauses: Design Controls, CAPA, and Complaints. Within Design Controls, DVal and Design Change are consistently among the most cited clauses. Within CAPA, be sure to document all your work. Within Complaints, document your investigations. If time is limited, concentrate on writing these procedures or improving these areas to make for smoother inspections.

- Although the number of FDA inspections has been hampered throughout the pandemic, FDA recently announced it had greatly exceeded its projections for the number of domestic inspections conducted toward the end of FY2021. If you have not taken advantage of FDA being distracted by higher priorities, get busy because they are coming.

About the Author:

Adam Atherton, PE, RAC, is an independent consultant to medical device and combination product manufacturers. He develops strategies to address technical feasibility, new product development, remediation, regulatory, clinical, manufacturing, and post-market surveillance for Fortune 200 medical device and pharmaceutical companies as well as startup ventures. He manages key aspects of design control, risk management, product architecture, and quality systems. He graduated from Naval Postgraduate School with his MSEE degree and from California State University, Fresno with his BSEE degree. He can be reached at www.keb-llc.com or info@keb-llc.com.

Adam Atherton, PE, RAC, is an independent consultant to medical device and combination product manufacturers. He develops strategies to address technical feasibility, new product development, remediation, regulatory, clinical, manufacturing, and post-market surveillance for Fortune 200 medical device and pharmaceutical companies as well as startup ventures. He manages key aspects of design control, risk management, product architecture, and quality systems. He graduated from Naval Postgraduate School with his MSEE degree and from California State University, Fresno with his BSEE degree. He can be reached at www.keb-llc.com or info@keb-llc.com.