The Voluntary Improvement Program: FDA Seeks Public Comment On Draft Guidance

By Mark Durivage, Quality Systems Compliance LLC

On May 6, 2022, the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) announced the establishment of Docket No. FDA-2022-D-0109 to solicit comments on the FDA's proposed Fostering Medical Device Improvement: FDA Activities and Engagement with the Voluntary Improvement Program. The purpose of the docket is to describe its policy regarding FDA’s participation in the Voluntary Improvement Program (VIP), which was facilitated by the Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC). The VIP uses a version of the Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) appraisal appropriate for the medical device industry referred to as the Medical Device Discovery Appraisal Program (MDDAP) model. The VIP evaluates the capability and performance of medical device manufacturing practices using third-party appraisals. The VIP is currently available only to eligible manufacturers of medical devices regulated by the CDRH and whose marketing applications were reviewed under the applicable provisions of sections 510(k), 513, 515, and 520 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

On May 6, 2022, the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) announced the establishment of Docket No. FDA-2022-D-0109 to solicit comments on the FDA's proposed Fostering Medical Device Improvement: FDA Activities and Engagement with the Voluntary Improvement Program. The purpose of the docket is to describe its policy regarding FDA’s participation in the Voluntary Improvement Program (VIP), which was facilitated by the Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC). The VIP uses a version of the Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) appraisal appropriate for the medical device industry referred to as the Medical Device Discovery Appraisal Program (MDDAP) model. The VIP evaluates the capability and performance of medical device manufacturing practices using third-party appraisals. The VIP is currently available only to eligible manufacturers of medical devices regulated by the CDRH and whose marketing applications were reviewed under the applicable provisions of sections 510(k), 513, 515, and 520 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

The CDRH's 2016-2017 strategic initiative was to “Promote a Culture of Quality and Organizational Excellence.” The CDRH envisioned a future where the medical device ecosystem is inherently focused on device features and manufacturing practices that have the greatest impact on product quality and patient safety. As part of this initiative, the FDA, working with the MDIC public-private partnership, developed the Case for Quality Voluntary Medical Device Manufacturing and Product Quality Pilot Program (CfQ Pilot Program).

The VIP oversees third-party appraisers who evaluate voluntary industry participants to assesses the capability and performance of key business processes using the CMMI developed by the Information Systems Audit and Control Association (ISACA).

Capability Maturity Model Integration

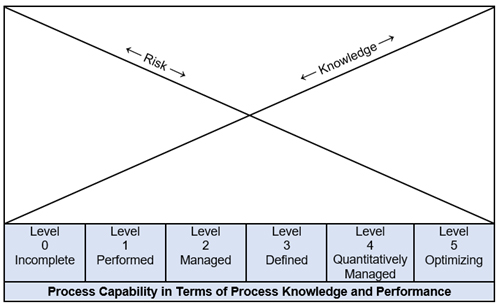

A company’s performance of key business processes is assessed to determine the level of maturity for each process. The basic premise of CMMI is the relationship between process knowledge and risk. Each process is assessed using predefined criteria to determine its level of maturity. Figure 1 depicts the relationship between capability, risk, and knowledge.

Figure 1: Capability, risk, and knowledge relationship.

CMMI Model – Capability Levels

CMMI capability levels refer to the capability of discrete processes. CMMI defines six capability levels as follows:

Capability Level 0: Incomplete

Level 0 refers to incomplete, unstable processes that do not have measures of effectiveness and/or efficiency.

Capability Level 1: Performed

Level 1 processes are performed; however, process performance may not be stable. Measures of process effectiveness and/or efficiency are generally not met.

Capability Level 2: Managed

Level 2 processes are managed. The process is planned, monitored, and controlled using measures of effectiveness and/or efficiency. Managing the process is aided with supporting metrics.

Capability Level 3: Defined

Level 3 processes are defined. Defined standardized processes are managed and meet the established measures of effectiveness and/or efficiency

Capability Level 4: Quantitatively Managed

Level 4 processes are quantitatively managed. These processes are controlled using appropriate statistical techniques. The process is well characterized with measures of effectiveness and/or efficiency that are refined using process data.

Capability Level 5: Optimizing

Level 5 process optimization focuses on continually improving process performance. Process improvements are incremental, innovative, and sustainable. Additionally, process knowledge is applied to other processes within the system.

CMMI Model – Maturity Levels

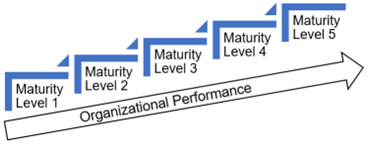

Maturity refers to the system (i.e., the collection of processes). A good analogy to the CMMI system maturity ratings is the widely known Bruce Tuckman's Forming, Storming, Norming, and Performing model for team development. Conceptually, Tuckman's model and the CMMI are in alignment, with Tuckman's model focusing on the maturity of a team and the CMMI on the maturity of a system. Figure 2 depicts the relationship between CMMI maturity and organizational performance. The CMMI has five maturity levels for the system, including:

Maturity Level 1

Level 1 individual processes are inadequately managed and/or improperly controlled, resulting in process outcomes that are unstable, unpredictable, and erratic. Level 1 processes do not have measures of effectiveness and/or efficiency; thus, the process is difficult, if not impossible, to improve.

Maturity Level 2

Level 2 individual processes are planned and controlled. A quality plan may have been utilized; however, the quality plan was potentially not comprehensive and/or not fully implemented. Measures of effectiveness and/or efficiency have been established but may not yield meaningful information.

Maturity Level 3

Level 3 individual processes are well defined using applicable regulations, standards, and procedures. Measures of effectiveness and/or efficiency have been established and begin to provide meaningful information. Process results may not be fully used to foster process improvement.

Maturity Level 4

Level 4 individual processes are characterized by using measures of effectiveness and/or efficiency that are driven by customer (internal and external) requirements. Process performance is analyzed using appropriate statistical methodology to look for opportunities for improvement.

Maturity Level 5

Level 5 individual processes show continuous improvement and performance. Process improvements are incremental, innovative, and sustainable.

Figure 2: Maturity versus organizational performance

VIP Quality Performance Metrics

VIP quality performance measures include safety, effectiveness, reliability, and availability. The VIP expects the participating organizations to develop their own targets or goals. The information provided by the participating organizations include:

- the quality objective of the measure

- business objective of the measure

- name or title of the measure

- the level of the measure

- how the measure is calculated

- indications of good performance

- known limitations of the measure or data

- why the measure matters/how the measure is used

- how often the measure is captured

- how often the measure is reported within the organization

Expectations Of VIP Participating Sites

The FDA registered manufacturing facilities will be anticipated to:

- Receive an annual third-party appraisal

- Engage with appraisers and commit to the proposed appraisal process

- Perform a quarterly progress check-in with lead appraisers

- Submit quality performance measures (safety, effectiveness, reliability, and availability)

- Notify FDA regarding product safety issues or recalls

The appraisal reviews the following topics:

- Estimating (EST)

- Governance (GOV)

- Implementation Infrastructure (II)

- Monitor and Control (MC)

- Managing Performance and Measurement (MPM)

- Product Integration (PI)

- Planning (PLAN)

- Requirements Development and Management (RDM)

- Technical Solution (TS)

- Configuration Management

- Process Quality Assurance

- Incident Resolution and Prevention (IRP)

- Organizational Training

FDA Activities & Engagement

The FDA intends to consider the benefit-risk considerations in its planning and to improve FDA resource allocations, improve review efficiency, and inform risk-based inspection planning for firms that demonstrate capability and transparency around their manufacturing and product performance.

The FDA anticipates that it will gain insights into the participating organizations’ manufacturing processes and control capabilities that will address some recommendations for regulatory submissions. VIP participating organizations may benefit from efficiencies that might prevent duplicate information and/or allow for the least burdensome approach for submissions to the FDA.

Participation in the VIP does not alter the participating organizations’ existing regulatory obligations under the FD&C 303 Act, nor does it impact FDA’s enforcement authority under the FD&C Act.

Conclusion

Participation in the VIP should not be considered a substitute or a replacement to a comprehensive internal audit program but, rather, as tool to supplement the internal process.

Obstacles to the MDDAP include:

- the supporting documentation is proprietary

- it is difficult to directly contacting an ISACA representative about the program

- the evaluation criteria are not publicly available.

Make sure you are heard: Submit written comments before July 5, 2022, to the Dockets Management Staff (HFA-305), Food and Drug Administration, 5630 Fishers Lane, Rm. 1061, Rockville, MD 20852 or electronic comments to https://www.regulations.gov. Please reference docket number FDA-2022-D-0109 with all comments.

About The Author:

Mark Allen Durivage has worked as a practitioner, educator, consultant, and author. He is managing principal consultant at Quality Systems Compliance LLC, an ASQ Fellow, and an SRE Fellow. Durivage primarily works with companies in the FDA regulated industries (medical devices, human tissue, animal tissue, and pharmaceuticals), focusing on quality management system implementation, integration, updates, and training. Additionally, he assists companies by providing internal and external audit support as well as FDA 483 and warning letter response and remediation services. He earned a BAS in computer aided machining from Siena Heights University and an MS in quality management from Eastern Michigan University. He holds several certifications, including CRE, CQE, CQA, CSSBB, RAC (Global), and CTBS. He has written several books available through ASQ Quality Press, published articles in Quality Progress, and is a frequent contributor to Life Science Connect. You can reach him at mark.durivage@qscompliance.com with any questions or comments.

Mark Allen Durivage has worked as a practitioner, educator, consultant, and author. He is managing principal consultant at Quality Systems Compliance LLC, an ASQ Fellow, and an SRE Fellow. Durivage primarily works with companies in the FDA regulated industries (medical devices, human tissue, animal tissue, and pharmaceuticals), focusing on quality management system implementation, integration, updates, and training. Additionally, he assists companies by providing internal and external audit support as well as FDA 483 and warning letter response and remediation services. He earned a BAS in computer aided machining from Siena Heights University and an MS in quality management from Eastern Michigan University. He holds several certifications, including CRE, CQE, CQA, CSSBB, RAC (Global), and CTBS. He has written several books available through ASQ Quality Press, published articles in Quality Progress, and is a frequent contributor to Life Science Connect. You can reach him at mark.durivage@qscompliance.com with any questions or comments.